Former FBI agent Coleen Rowley discusses still unanswered questions about the lead-up to 9/11. This interview was produced October 23, 2009, with Paul Jay on Reality Asserts Itself.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network, coming to you today from our studio in Washington, DC. We’re joined today by Coleen Rowley, a former FBI agent. She used to work in the embassy in Paris, she worked at the consulate in Montreal, she became a special advisor to the FBI on legal issues in Minneapolis, and she blew her whistle on 9/11 issues. And that’s what we’re going to talk about. Thanks for joining us.

COLEEN ROWLEY, FORMER FBI AGENT AND WHISTLEBLOWER: Thank you.

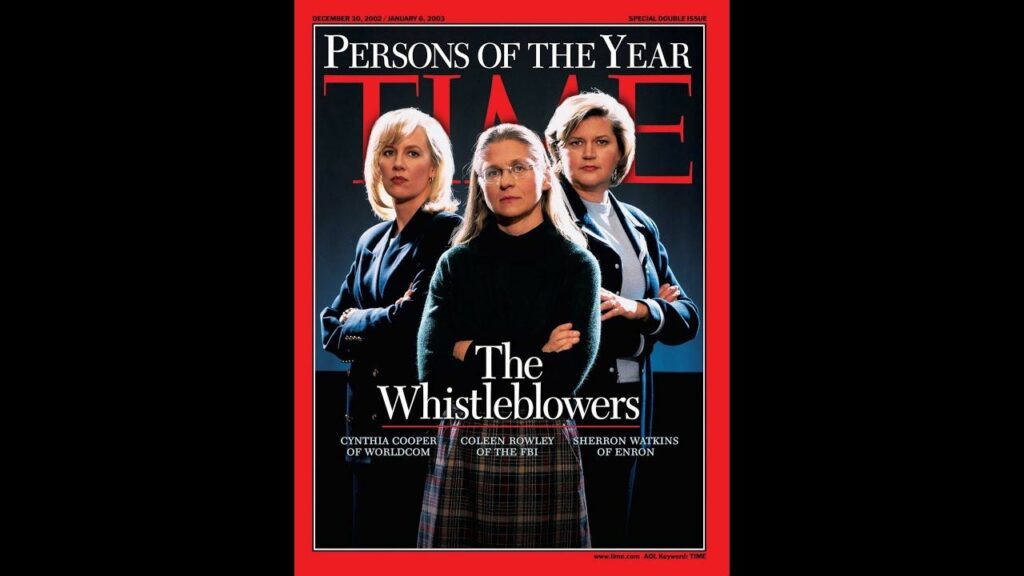

JAY: And behind you is you on the cover of Time Magazine, where you were picked Time person of the year for what you did in terms of exposing the lack of investigation of what the Minneapolis FBI office found.

ROWLEY: Yeah, 2002 was a year of whistleblowerS, because there was the Enron and the WorldCom collapse. So we had three females that were all on the cover of Time.

JAY: So let’s go back a little bit, just for people that don’t know this story. I think most people do, but we do live in an era of amnesia when it comes to political events and news. So lay out the basic events again of what happened.

ROWLEY: Well, in August 2001, a flight school in Minnesota called the FBI, and two of our agents responded very quickly. One of them was an INS agent [Immigration and Naturalization Services]. And they found that this was extremely suspicious for a person just to plop down cash and ask to learn how to train to fly a jet, but had no good explanation. The flight instructors were very instrumental, because they gave all these indicia factors of why they were suspicious. It was the most unusual customer who had come in to learn flight training that they had ever had. So the agents then pursued that very quickly, and they sent leads out to France and to Great Britain and to headquarters and got good information back pretty quickly. They put it all together.

JAY: This is information about who this guy was.

ROWLEY: About [Zacarias] Moussaoui and the potential for terrorism. They put this all down in a multipage draft declaration asking for further authorization to search his personal effects and laptop.

JAY: And give us the date.

ROWLEY: Well, he was detained on August 16. The call had come in the day before, I think, August 15. And, again, the fact that they reacted so quickly just shows you the importance. Normally if the FBI gets a normal, garden-variety crime tip, they don’t necessarily run out and do these things around the clock. And I even got called at nine o’clock on the night of Moussaoui’s detention. So that was unusual. I got called at—I was in bed, you know, and they said, “Oh, my goodness, let us run down what we just saw here,” and they told me.

JAY: So we’re seeing, like, an episode of 24 Hours [sic]. Jack Bauer’s just been called: “We may have a guy who’s learning how to fly a plane for terrorist purposes.” And Bauer picks up the phone and calls headquarters, and—.

ROWLEY: Well, you know, of course, 24, I don’t even know if it was running back in August 2001, but it actually was a bit of a scene out of something like that. The agents’ astuteness about this, one reason is the case agent was himself a former pilot and he was former military intelligence, and he spotted all of these suspicious factors very quickly. But that unfortunately contrasted with a disinclination to want to do anything about this at headquarters and to really see that significance.

JAY: So, quickly, what happens? Your office contacts headquarters. You want, essentially, authority to get warrants.

ROWLEY: Right. The agents—

JAY: And you don’t get it.

ROWLEY: —the agents—and this is actually pretty well spelled out in the 9/11 Commission report, but they send in a multi paged draft declaration chock-full of facts, as you would in any affidavit, of why they needed the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court to give authorization to conduct a further search. And when it goes into headquarters, it gets stalled and it gets—this is of course what I wrote the memo about, but it gets stalled for “Oh, he might be in the Zacharias Moussaoui.” You know, “We need to check the phone books to make sure it’s the only one.” I mean, there’s all these ridiculous excuses given. Finally, they say that the legal unit in the FBI read it and said there’s not enough probable cause. Okay? It turns out the legal unit had not actually read it. So you don’t know these things, though, when it’s happening. And the agents, of course, are very frustrated, and they call and they call. When the agent testified in Moussaoui’s trial, there were 70 emails to and from headquarters in this short two-week span. And one of the telephone calls in August—I’m not sure of the exact date, 23rd, 24th, 28th maybe—one of the telephone calls, the acting supervisor says on the phone with the headquarters supervisor, in order to try to alert him, he says, “Don’t you know this is a guy who could fly into the World Trade Center?” quote-unquote, and he wrote it down in his notes as he was talking to the headquarters supervisor. So things happen. The affidavit actually gets watered down a little bit. Some words get changed. You know, all these things happen. And a backup plan later is produced in early September, because headquarters says, “No, we will not even take this over to the Department of Justice.” And so at that point, then, the plan was for Moussaoui to be deported to France, and then they were going to do the full search there. And that’s where it stood right on 9/11 when, you know, we see planes flying into buildings. And as soon as planes fly, you know, you see this on the television, it’s like, “Oh, no, this is the case here.” It was immediate; it’s that quickly that it’s recognized.

JAY: Now, just in the same period, I think it’s just a few weeks before if memory serves me right, Condoleezza Rice gets a memo which says bin Laden plans to attack America. And even though she tried to suggest it was some sort of historical reference, if you read the memo the last point of the memo is quite clear, that there’s strong suspicion there are actually plans afoot to attack America, not just some historical document. She says to the 9/11 Commission, more or less, that when asked, “What did you do about it once you get this memo?” that she sent it to FBI offices. But that turned out not to be the case.

ROWLEY: Well, of course, I knew nothing about Condoleezza Rice’s memo that she would have seen. I did not know either that our FBI had gotten a memo from the Phoenix office at about the same date as Condoleezza Rice had this memo, saying look at flight schools, because there are potential terrorists training to fly in flight schools. And I think this was July 10 or 11. And, of course, when you’re compartmentalized in the intelligence community, you’re not privy to everything flying around. We do know—and I think our office was on some alert for terrorism—later on, our acting director, [Thomas] Picard, tells the 9/11 Commission that he was actually trying to brief Ashcroft, the attorney general, about terrorism being a priority. And so throughout that summer things were happening. It’s just that when you’re, you know, kind of in a small cog, you may not [be] privy. And, of course, that’s one of the things that we needed to address after 9/11 was why weren’t the dots connected and why was not this intelligence shared.

JAY: Now, in the same summer, Richard Clarke testified at the 9/11 Commission—Richard Clarke being the antiterrorism czar, except he’d been reduced from being czar to, I don’t know, general or something, because he was a cabinet-level position under Clinton and gets demoted under Bush to, I guess, something akin to an undersecretary, I suppose. Would that be a correct—?

ROWLEY: Well, he was put off. I mean, he had this plan that was well written already, and trying to get more emphasis and resources.

JAY: So again a deliberate decision. You look at your cabinet, you have someone who the Clinton administration and all your security, intelligence people have said need to be there at a cabinet level, and you don’t. What is the logic of this pattern of being not interested in a potential terrorist attack?

ROWLEY: Well, I can only speak for my own experience, and I know that crime and—. Certainly in the FBI there’s something called “flavor of the day”. You know, in the ’80s it was mafia cases, and those were the things that got the attention, and maybe it was because of the crime problem at the time. And other times there is an arbitrary—it can be selected, saying, “This is what you need to look at.” There’s a prioritization of crime programs. And in the summer of 2001—I think this was actually August—Ashcroft prioritizes terrorism as his lowest priority. So, again, Picard says, “I was trying to brief Attorney General Ashcroft—.”

JAY: And just again let’s remind us who Picard is.

ROWLEY: He was the acting director of the FBI. In June, Louis Freeh had retired, and Picard became the acting director. And he claims that he tried to brief Attorney General Ashcroft that summer on the importance of terrorism.

JAY: But why can’t the FBI—and Ashcroft wasn’t interested in terrorism, but why can’t the FBI on its own make it a priority? Because if you look at the FBI ten most wanted list, who’s number one? Osama bin Laden. And this is before 9/11. He was, like, number one for, I think, two or three years before that.

ROWLEY: Well, an investigative agency can’t totally act on their own, because if they are investigating things, they can do wonderful work, but it’s got to be prosecuted. So they always have to make those decisions about what is the priority crime in connection with the Department of Justice, because they have got to have those prosecutive resources. If they decide, you know, “Mafia is the thing that we’re going to look at,” and the Department of Justice says, “No, it’s failure of S&Ls,” they’re not going to get very far if they put all their resources. So those decisions about what’s the priority now, usually they’re precipitated by actual events. You know, if you have an S&L collapse, the priority then is shifted to, you know, that type of thing. If you have corruption, it’s shifted to corruption. After 9/11, resources were, you know, hugely diverted to intelligence and to the study of terrorism.

JAY: You have this—Osama bin Laden, as I said, is number one on the FBI most wanted list pre-9/11. You have Richard Clarke saying to the 9/11 Commission, “Our hair’s on fire, there’s so much traffic and chatter about an impending event.” We’ve heard that at least a couple of foreign governments tell the American government something’s coming. We all know now, and many knew before, that the Pakistani ISI were up to their eyeballs in the Taliban and al-Qaeda. Very difficult to believe there’s something being planned by an al-Qaeda based in Afghanistan that the Pakistani ISI wouldn’t know about, thus the Sauds know about. We know there’s 27 pages of redacted pages, the 9/11 Commission, which, according to The LA Times, detail names of the Saudi members of the royal family and the government that directly connected to 9/11 conspirators. I mean, all of this going on. We know Prince Bandar’s visiting the White House once a week. He’s practically got his own key to the washroom. There’s just too much going on here that you wouldn’t think that the FBI wouldn’t have been put on alert. It doesn’t make any sense.

ROWLEY: Well, again, I think that the directions to investigate terrorism—again, there was a disconnect between the Department of Justice and the FBI, and with the new administration, agencies are all kind of checking out what is this administration going to want from us, you know, what’s our priority. So I can’t explain, except that these dots, of course, that come in and these pieces of information and tips and things that came in were not taken seriously in the summer of 2001.

JAY: Well, in the next segment of our interview, let’s talk about what these events and this last seven, eight years have done for Coleen Rowley, ’cause it must have done a lot to change the way you look at the world. So please join us for the next segment of our interview with Coleen Rowley.

[powerpress]

[simpay id=”15123″]

“Coleen Rowley is an American former FBI special agent and whistleblower and was a Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party candidate for Congress in Minnesota’s 2nd congressional district, one of eight congressional districts in Minnesota in 2006. She lost the general election to Republican incumbent John Kline.”