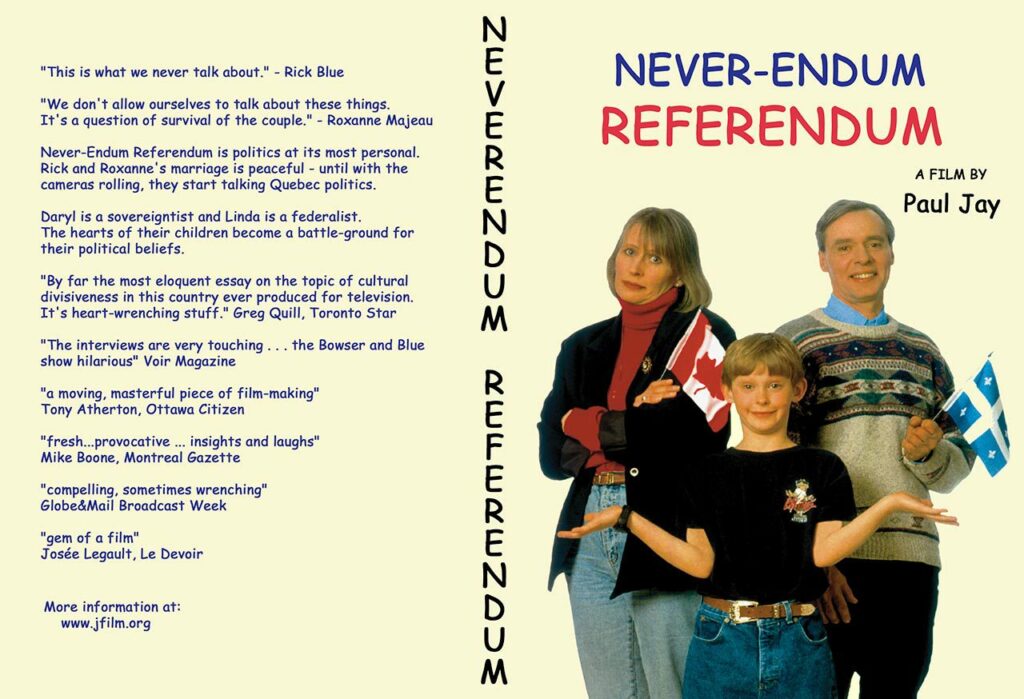

“This is what we never talk about.” – Rick Blue

“We don’t allow ourselves to talk about these things. It’s a question of survival of the couple.” – Roxanne Majeau

Never-Endum Referendum is politics at its most personal. Rick and Roxanne’s marriage is peaceful – until with the cameras rolling, they start talking Quebec politics. Daryl is a sovereigntist and Linda is a federalist. The hearts of their children become a battle-ground for their political beliefs.

“By far the most eloquent essay on the topic of cultural divisiveness in this country ever produced for television. It’s heart-wrenching stuff.” – Greg Quill, Toronto Star

“The interviews are very touching . . . the Bowser and Blue show hilarious” – Voir Magazine

“A moving, masterful piece of film-making” – Tony Atherton, Ottawa Citizen

“Fresh…provocative … insights and laughs” – Mike Boone, Montreal Gazette

“Compelling, sometimes wrenching” – Globe&Mail Broadcast Week

“Gem of a film” – Josée Legault, Le Devoir

Q & A with Paul Jay

Q. What prompted you to make this film

A. Filmmakers are always looking for a story to tell, and this is one that’s been on my mind for some time. Like most Canadians, I’m frustrated with the level of political debate about Quebec’s relationship to the rest of Canada. In the heat of the political rhetoric, real people become abstractions and all we see is the posturing of politicians on both sides, who fight principally for their own power. I felt we needed to humanize the discussion, so that people in English and French Canada could see that their concerns and dreams weren’t that different from each other.

I was hit with the idea, I know it’s not so original, that the place where English and French Canada really meet, is in the relationships of the Anglophones and Francophones of Quebec. The Quebec Anglos form a kind of bridge between the two societies. Before the last Quebec referendum, many of the Anglos of Quebec had really come to feel at home in the new Quebec. They were sending their kids to French schools, learning to work in French, and had more or less come to terms with Bill 101. Many were very frustrated at Canada’s inability to accept two obvious things . . . that French society in Quebec is not the same as English society in the rest of the country and that this society is threatened, needs to be recognised and believe it has the tools to defend itself. I hoped that through the personal relationships of the Anglos and Francos of Quebec, English Canada might get a better understanding of this reality of Quebec life.

Q. You say you hoped. Did things change?

A. Yes. Parizeau’s speech about money and the ethnic vote being the cause of the defeat of the “yes” side, and the closeness of the results, scared the hell out of most of Quebec’s Anglos. No longer did the Anglos feel at home in Quebec. They were once again ‘les autres’, the others, the outsiders. They were to blame. One Anglo woman, who is in the film, had supported Bill 101 language laws. After the referendum she became a partitionist. After the vote, there were calls from the hard core separatists to strengthen language laws, and cutback on services to Anglophones in Quebec. Many Anglos felt like they simply weren’t wanted.

I found as blind as much of English Canada is to the concerns of French Quebec, French Quebec is just as blind to the concerns of the Anglos living in their own backyard.

As Jacques Godbout says to Josh Freed in the film, “the relationship of your community to my community, is like that of my community to Canada.”

So when I started filming, the Anglos were not much in the mood to make a plea for Quebec’s rights to the rest of the country. They were much more interested, and understandably so, in defending their own rights.

Q. So did this change the direction of the film?

A. Yes. When Radio Canada became involved, we had the opportunity to address the French audience as well. Now the film attempts to break down stereotypes on both sides of the fence. It’s really a very unique broadcasting window. When the film first aired, on Baton Broadcasting and Radio Canada, English and French Canada watched the same documentary program, in their own language, on more or less the same evening. I don’t think there has ever been such a thing before.

This is really a statement in itself. Why on earth is this a first? Outside of hockey games, it’s really amazing how separate our two cultures really are.

Q. The film focuses on Anglo/French couples and friends. Why?

A. These relationships are a metaphor and the reality of where English and French society in Canada meet. Even here, with people who are most intimate with each other, there is difficulty in understanding each other’s sense of national identity.

Most of the relationships in the film are ‘yes/no’, as far as voting in the referendum goes. But even though they disagree, and sometimes with a great deal of tension, these relationships work. As one subject says, they love each other, they function, they raise wonderful kids. They have found a way to live together.

The one thing almost all of our subjects agreed on, was that they hate the political process. They don’t want to have to choose yes or no. They want a compromise. They want to find a solution. And all of them, blame politicians for manipulating people’s emotions, and the media for allowing extremists to monopolize the debate.

So, in this film we wanted to give a voice to ‘ordinary people’. Of course we found they were far from ordinary. Most of the voices you will hear in the film are far more articulate and insightful than that of most politicians and media pundits you are likely to hear.

Q. Did you learn anything new while you were filming?

A. Of course, many things. I hadn’t understood just how separate English and French societies in Quebec are. Even many smart, educated French people hadn’t heard of writer Josh Freed, who is one of the best known Anglos in Montreal. Most of the Anglos, even those that speak French, watch English TV and movies and know little about contemporary French popular culture.

I’ve often thought one of the great mistakes we made as a country was splitting our national broadcaster so completely along linguistic lines. Why couldn’t we have grown up watching each other’s programs with subtitles? Quebec has such a rich modern culture, really world class, and in the rest of the country we know so little of it. To many French in Quebec, English Canada is less known than the United States, because they see so much American TV.

Q. What else made an impression?

A. Perhaps the most significant thing I learned was how much French Quebec has a national psychology that is different from English Canada’s. It’s not just language, although clearly language is at the heart of it. It’s also having to do with being a relatively homogeneous society for several hundred years. All the things that make up a national psychology – traditions, common economy, habits, religion, family customs, folklore, songs, etc., etc., and of course language – are to be found in Quebec every bit as much as you find in any other nation. I don’t know why we find it easy to grasp that there is such a thing as the national psychology of an Italian, or a German or an Englishman, but somehow we think that Québécois lack this. As much as Europe becomes more unified, the individual nations do not give up their national psychology and the culture that reflects it without a fight.

The native peoples have their own national psychology too, as specific as that of the French. They are also threatened, more so really, as they have far less political and economic power to defend themselves.

Q. What does this mean for you?

A. As an English-speaking Canadian, I have a national psychology too, but it is different. Many of us came here from other countries, more recently, and our ancestors who immigrated, made a choice to break most ties with their national roots. Each generation adopts more of a new Canadian national sense, which is linked to a relatively modern experience, and to contemporary mass culture. Most of us don’t have hundreds of years of traditions and ancestors to, as one woman in the film says, act as a kind of shadow walking behind us. It’s not to say there is anything less modern about the Quebec people, it’s just these factors play a stronger role.

For me, national and cultural identity has less to do with who I am than might have been if I had grown up as a French Quebecer. I don’t see this as any better or worse, just different.

Q. Did the process of making the film, change the way you looked at the situation?

A. Making a film always changes me. It’s as much an exploration for me as I hope it will become for my audience. This film made me understand how little I knew of Quebec. When I was in grade five, we started studying French. I asked my teacher, why should I learn it? Her answer was that I might take a trip to Paris some day. There was no mention that almost a third of my country spoke French. One young woman I interviewed grew up in Alberta and went to a French immersion school. All her teachers but one came from France.

The more I came to know Quebec society, the more I felt like I was making a film in another country.

Q. Did you come to any conclusions?

A. Many, but two were most important. The first was that if moderate French society really wants the Anglophones and Allophones to feel at home, they had better speak out against their own extremists, and oppose those who are trying to turn Francoization into some kind of religion. If they don’t build Quebec on democratic principals, and defend minority rights, then I don’t know what kind of society they will have.

The other is if Canada wants Quebec to feel at home, we’d better recognise the fact of French Quebec’s national psychology. It’s not a question of being distinct, or unique, or any other compromise fudging of the issue. It’s the psychology of a nation. If we don’t, we are refusing to accept a reality. It also has to do with how democratic our society will be.

Q. Do you think Quebec should separate?

A. No. I don’t see why there can’t be room for more than one national identity within a single country. If we can accept what French Quebec is, and make sure they feel they have the political tools to defend their identity, I don’t see why we can’t be together in one country. On the other hand, if we pretend Quebec is just like any other province, and mix the Quebec question up with the issue of decentralizing the federation, then we have a problem that won’t go away until there is a yes vote.

Q. Is it really worth all this endless debate and political wrangling?

A. I believe it’s worth making the effort. As a Canadian born and raised in Toronto, I think it’s in my interest to keep Quebec in the country. We live at a time when the international scene is very competitive, even predatory. Size does count for something, and Canada and Quebec would be more vulnerable on their own.

I also think that the Quebec people are a good influence on Canada. I think my country would be less interesting, more American, and politically more conservative without them.

It goes the other way too. There have been times in Quebec’s history when a more enlightened influence came from the rest of Canada. I don’t think the dark side of the nationalist movement should be minimized. It’s not dominant, but it exists.

Of course, we must get over the never ending diversion of the sovereignty debate. It couldn’t be more boring for everyone. This was the major challenge of the film. How to treat a subject everyone is sick of.

Q. Can we get over this endless battle?

A. I hope so. I really don’t believe in the final analysis that most Canadians oppose recognition of Quebec’s right to defend its national identity. What they don’t like is the feeling that Quebec is getting “more than its fair share.” They want to know that in exchange for more powers, Quebec is paying its own way. There is a feeling across Canada that successive federal governments have tried to bribe Quebec in order to appease the separatist forces. Whether this is true or not is beside the point. The perception is very wide spread. A solution can be found if it is clear that in exchange for more powers, Quebec pays its own way.

There is also a perception more powers for Quebec means those citizens will have more rights than other Canadians. I’ve never understood this. As someone in Toronto, what do I care if some of the services I get delivered through the federal government, my counterpart in Montreal gets delivered through his provincial government. I think this is a confusion deliberately created by politicians and pundits who like to fish in troubled waters.

Q. Where is patriotism in all this?

A. I don’t believe the unity of Canada should be a religious principle, any more than the idea of an independent Quebec should be. Countries are a means to a better life, not an end in themselves. If people can see past the bickering of politicians and narrow interests, I think we can work this out.

Q. Did you have personal reasons for making this film?

A. Everything I’ve said has to do with my personal interest. But there is something specific. My father was an Anglo from Montreal, who moved to Toronto in the ’50s. I often visited as a child, so I always felt a tie. My uncle was a writer, and I grew up with his stories about Montreal. My wife is Francophone, born in Montreal, her parents are Franco-Albertan and Franco-Manitoban. Through our relationship I have understood better, though we are both Canadians, the significant differences in our backgrounds.

Q. With the completion of the film, are you more or less optimistic about Canada’s future?

A. More. While the film tries to be realistic, and not put a rosy filter on things, in the end I found that most people want to solve this thing. All the relationships in the film work, in spite of the cultural and political divide.

We need to humanize the discussion, so we aren’t dealing with abstractions about what a Canadian is and what a French Quebecois is, and see that we are talking about people who are like us – they want a home, a better life, a sense of purpose and dignity.

My favourite part of the film is about a black woman, a dancer. She says she wanted to teach dance and be a nursery school teacher. Now she is doing both, her dreams have come true. She says she wants other people’s dreams to come true too. I’m with her. We need to have more understanding and respect for each other’s dreams.

This is what we never talk about.” – Rick Blue

“We don’t allow ourselves to talk about these things. It’s a question of survival of the couple.” – Roxanne Majeau

Never-Endum Referendum is politics at its most personal. Rick and Roxanne’s marriage is peaceful – until with the cameras rolling, they start talking Quebec politics. Daryl is a sovereigntist and Linda is a federalist. The hearts of their children become a battle-ground for their political beliefs.

The Globe and Mail – “remarkable . . . a voice that is full of love and humour and pain”

Ottawa Citizen – “a moving, masterful piece of filmmaking about a touchy subject”

Le Devoir – “There is nothing ordinary about this film . . . wonderful”

Toronto Star – “By far the most eloquent essay on the topic of cultural divisiveness in this country ever produced for television. It’s heart-wrenching stuff.”

Montreal Gazette – “One can only hope that politicians are as perceptive, open-minded and compassionate as Paul Jay”

Globe & Mail Broadcast Week – “compelling, sometimes wrenching”

StarWeek – “amusing and sometimes chilling . . . fascinating”

Windsor Star – “brilliantly simple . . . a coup for Canadian film-making”

Le Devoir – Josée Legault – “gem of a movie”

Voir Magazine – “The interviews are very touching . . . the Bowser and Blue show hilarious”