On Reality Asserts Itself, Robert Scheer talks about democracy, journalism, and his new book, “They Know Everything About You: How Data-Collecting Corporations and Snooping Government Agencies Are Destroying Democracy”. This interview was originally published on June 9, 2015.

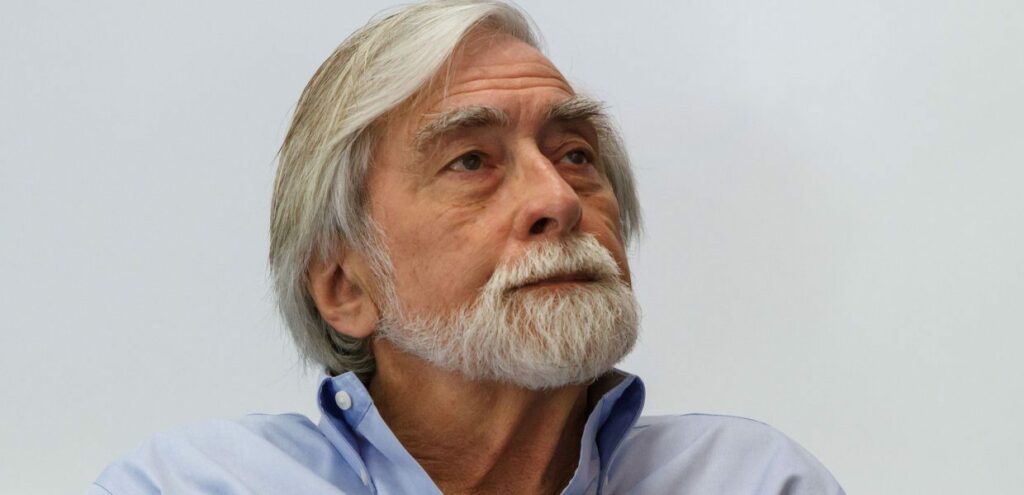

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay. In the book by Robert Scheer They Know Everything About You: How Data-Collecting Corporations and Snooping Government Agencies Are Destroying Democracy, Robert Scheer writes, the main price paid by turning the war on terror into a war on the public’s right to know–a bipartisan crusade–is that it destroys the foundation of democracy–an informed public. The George W. Bush administration initiated this dangerous trend, and Barack Obama has expanded on that horrid legacy by cracking down on the press and prosecuting whistleblowers under the Espionage Act more than all previous U.S. presidents combined. The result is that our privacy, and hence our freedom, has been plundered with abandon. Our most private moments are now captured in exquisite detail by a newly emboldened surveillance state, resulting in a shutdown of democracy. But the game’s not over yet. That was written by Robert Scheer. Robert is a veteran U.S. journalist, currently the editor-in-chief of the Webby Award-winning online magazine Truthdig. He’s also a professor at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, cohost of Left, Right & Center, a weekly, syndicated radio show broadcast from NPR’s West Coast affiliate KCRW. In the 1960s, he was the Vietnam correspondent and editor of the Ramparts magazine. He also ran for office as an antiwar candidate in congressional races. For decades, Bob was the national correspondent, and then columnist, for the Los Angeles Times. He’s the author of nine books, including the one I mentioned, as well as The Great American Stickup and The Pornography of Power. And Robert now joins us in the studio. Thanks for joining us.

PROF. ROBERT SCHEER, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: How are you doing, Paul?

JAY: So, for those of you that watch Reality Asserts Itself, before we kind of get into what our guest thinks, we usually talk about why our guest thinks what they think–in other words, what helped form the way they look at the world. And this segment, and also a little more of this series with Bob, is going to be quite biographical, ’cause he’s lived somewhat of a legendary life. He’s one of the most important figures that came out of the left and out of progressive journalism. And we’re kind of honored to have you here today. Thank you.

SCHEER: Yeah.

JAY: That being said, I will try to give you a hard time at times if I can.

SCHEER: Well, you know, the question you just posed, what forms your interest, it’s interesting. My motto as a journalist–and I take the journalism seriously. So when I’m in your seat and I’m interviewing–you know, I’ve interviewed Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan and Fidel Castro and Mikhail Gorbachev, lots of people all over the world. And were I beginning this interview, I would psyche myself up to assume that you know things I don’t know and, as you tell kids, have your listening years on and prepare to be surprised, prepare to learn something. And rather than follow some script, I’d want to know, you know, okay, what’s going on here? What do you really think? What can I learn? And maybe I’m full of it. Maybe I’ve been wrong.

JAY: Right.

SCHEER: And it’s a hard thing to work yourself in. You know, I traveled with Jerry Falwell, you know, on the religious right, and there wouldn’t be any point to spending the weeks I did to do a profile of Falwell when he was head of the Moral Majority and everything if I couldn’t get myself psyched up to think he may be right and I may be wrong. And so that’s always been a challenge. At the same time, going to your question, I follow the motto of the great beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, for whom I worked for three years at City Lights bookstore in San Francisco when I lost my fellowship money at UC Berkeley ’cause I dared to publish–[at perish (?)] publishing I dared to publish a book about U.S.-Cuban relations that my department didn’t like. So I lost my money, and I went to work and sold books for a buck and a quarter an hour for three years and did a lot of reading, got a lot of my real education. But Lawrence Ferlinghetti once said, keep an open mind, but not so open that your brains fall out.

JAY: Yeah, that’s a good one. Now, you do understand that in this interview, you have already started interviewing yourself, ’cause I haven’t asked the first question yet.

SCHEER: You did. You asked, what drove you, how–.

JAY: Yeah, no, I didn’t get to ask it to you.

SCHEER: Oh. Oh.

JAY: I told the audience that’s what we were going to do.

SCHEER: Okay. Well, put that question to me and I’ll answer it.

JAY: Alright. Well, let’s start from the beginning. Tell us a little bit about your parents, but particularly about the politics of the household you grew up in.

SCHEER: Well, there’s two formative experiences I had growing up that have very much influenced, if not dominated, my journalism. I have never escaped it. One is I was born by an accident. My mother had had three abortions before me. She was an unmarried, single woman who had been very active politically in czarist Russia, and then, when the revolution happened in Russia, she was in a group called the Jewish Socialist Bund. And then Lenin and the Bolsheviks moved against her group. And so, in 1921, my mother fled Russia and came to the United States. But being of a temperament to rebel–she had rebelled against the rabbis, she’d rebelled against the Czar, and she rebelled against the Bolsheviks. And being a working person–my mother made sweaters, worked on what was called a /ˈmɛrə/ operators machine, which they still have, although they’ve been replaced by computers that spin out, but there’s still some of that done. And so my mother was working first in a candy factory, and then in the garment–and worked in the garment industry for basically sweatshops until she was 65. And even when I started making a little money, she wouldn’t give it up, ’cause she wanted to get her Social Security and pension.

JAY: Now, some people that were in that situation fled the Soviet Union, got into a fight with the Bolsheviks, come to the United States, and often kind of get assimilated into the American political culture, even on the right, you know, pick up a lot of the anticommunism. Did that happen to her?

SCHEER: No. First of all, I think the people you’re talking about, they–you know, some of them were quite prominent and then moved over to the right, you know, and even into the CIA and everything, you know, ’cause they had the language skills. But my mother–and this goes to formative experience–my mother and my father–well, I’ll tell you about–these were really working class people. Neither of my parents had graduated from high school in their own country. And yet they were what I can call working-class intellectuals. We used to have Haldeman-Julius–really, the first paperback, little books. There was a series, Haldeman-Julius, Blue Books. And I remember even when I was a kid they were around, and you could get Plato’s Republic, you could get the U.S. Constitution, and you could get Marx’s Capital in reduced form. It was like the Reader’s Digest for working people. And you could buy these things, put it in your back pocket. On the subway, you could be reading Aristotle or something, you know, or–. And so my parents were very much of that kind. They were culture vultures, we used to call them. They would go to all the free lectures in downtown New York and Manhattan. They would go to the museum. And they’d be in standing line at the opera or the ballet. My father, who came from Germany, was a musician also, and we could talk about that. So my parents, they soaked up knowledge and information.

JAY: What was the fight with the Bolsheviks about?

SCHEER: Well, the Bolsheviks were opposed to any nationalist movement, and this was the Jewish Socialist Bund. It was a movement that was not accepting of Zionism–they didn’t want to build a country somewhere else. But they did want to retain Jewish identity, and they were, you know, more or less secular Jews, but rebelling against the harsh orthodoxy of the Old Testament Jews. But nonetheless, they spoke Yiddish. They came from the Yiddish pale. They had a real strong cultural identity, which they didn’t want to abandon. Yiddish was actually their main language.

JAY: And what was the Bolsheviks’ problem with that?

SCHEER: Well, the Bolsheviks were–.

JAY: ‘Cause they accepted that with other nationalities.

SCHEER: Well, then you’re jumping ahead in the story. What happened with the Bolsheviks is they had an idea of kind of a meaningless expression of nationalism: you stay in your place, you–. In fact, they formed a place called Birobidzhan, which was supposed to be for Jews, but most Jews rejected it–that was not what they had in mind. And, you know, I don’t want to trace that whole history. Let’s just put it this way. My mother was a young woman. Two of her sisters had been killed by the czar. She was part of a generation of young Jews, working-class Jews–that’s very important to remember. My mother worked as a seamstress. She worked for–my mother had a memory–it was funny, ’cause when Kennedy was president and he was married to the Radziwiłł, right–his wife came from the Radziwiłłs, a Polish family. And my mother had made drapes for the Radziwiłłs, because she was right on the border with Poland, and the countries were changed. And she had childhood memories of being taken when she was 12 or 13, with the other people working in her drapery factory, out there to measure the drapes for the Radziwiłłs, and then working for the next year to make these drapes. You know. And that was the sort of main work thing.

JAY: And your father was–.

SCHEER: So I just want to say, on my mother’s side, she got here and she, my mother, never became a citizen, because when she was here, she got arrested, I don’t know, ten times in the first few months in labor strikes in the Garment District in New York, and then the lawyers told her, hey, you’ve got a record now, don’t go apply. So she was a registered alien for all of her life, and at some point she couldn’t even find her papers and had trouble with the immigration service. So now when I live–I live in L.A., and I’ve covered the immigration issue very extensively, and through one of my sons I’m married into a family of people from Oaxaca, Mexico, and it’s very familiar to me. I go to the same kind of backyard barbecues that I went to in New York, and there’s the same mixture of languages, and people are working at very similar jobs, including the garment industry, but all the–parking cars, they’re working as maids. I had–on the German side of my family, I had–my aunt was a maid for a wealthy family in Manhattan, the /ˈdroʊʃɨz/.

JAY: Yeah, explain that, your father’s background.

SCHEER: Okay. So the thing is that my mother for some–because of her–you know, she was kind of a Emma Goldman type, but without the education. But she did read. My mother–let me just say something in praise of my mother, who lived with me until she died when she was 88, and she had Parkinson’s for about 20 years. My mother would alert me to political issues. And one of them, I’ll never forget it. And my wife, who was–ended up being the associate editor of the LA Times and a vice president, Narda Zacchino, we both had vivid memories of this. In the early ’80s, my mother said, you know, she was so depressed. We said–and she had Parkinson’s, she had her own problems, you know, she was kind of a frail woman. She was born exactly at the turn-of-the-century, so in the early ’80s she was in her own early 80s, or 82 or 83, say. And we said, why are you so depressed, Ida? Her name was Ida Kuran. My wife said, why are you so depressed? She says, oh, I’m reading a really depressing book. And she said, well, what’s this book? She says, oh, it’s about a new illness called AIDS, and you have to read about it. And, you know, I had heard about it, obviously, a little bit. And I said–this is the period when Reagan was denying there was such a crisis. And we said, why are you reading this? She said, oh, everyone should read this. This is–. You know. And why? Because my mother had a universal concern about suffering, okay? And so she was moved by this. And because of my mother, I started covering the AIDS crisis. And I covered it for the LA Times at a time when the paper was indifferent to it. And I can tell you stories about covering it. But I got very deeply involved in the issue–again, inspired by my mother. And on the other hand, she wasn’t always approving of my work. At one point I remember soon before she died–it must have been 1985, a couple of years before she died–I did a profile on Richard Nixon when he was living in New York and had his office in New York. And I wrote this big takeout in the LA Times that went for whole pages reevaluating Nixon. I’m pointing out that compared to Reagan he was quite moderate in his outlook and that he had had an idea of a guaranteed annual income and opening to China. And so it was kind of a favorable view of, you know, a revisionist view of Nixon. My mother was the first person that responded to it, ’cause she was in the kitchen, and she read this whole thing. And she had her glasses on at the end of her nose, and she’s reading every word of this thing without commenting. And I’m standing there. You know, she was the first human being who was reading this thing that I worked on for about three months. And then she finishes. And I say, so? What do you think? And my mother looks up and she–only thing she said: he needs you? I was crushed. He needs you? Yeah, Ma, that’s what I do. I’m a journalist. I’m supposed to figure these things out honestly. You know.

JAY: Well, we’re jumping around, but why did you write, why did you do this revisionist–.

SCHEER: I think when we’re jumping around it’s how we learn. You know. I tell my students that maybe it’ll be [incompr.] maybe it won’t, but it’s still interesting. Why did I do it? Because it struck me as more came out, you know, and more information and what had happened–and then I compared it to what Reagan was doing, and even what Carter had done, you know, sending–getting all involved in Afghanistan, and relations with the Soviets had deteriorated, you know, and Nixon, who I’d followed as a journalist–I’d followed his career. But I went back and I said, you know, Watergate in a way gave us a distorted view, and the bombing of Cambodia. You know, they’re terrible things. I’m not minimizing it. But he inherited the Vietnam War from the Democrats.

JAY: To some extent. I mean, there is evidence that he may have torpedoed the negotiations Johnson was involved in.

SCHEER: Yeah, but Johnson deserves the blame or credit for the Vietnam War, and it was a Democratic war, Democrats, and it was done to stop Goldwater. I mean, you could say there was pressure from Republicans.

JAY: What do you make of the–there seems to be–I mean, Johnson certainly accused Nixon; he called him acting like a traitor for sending this emissary to try to block the negotiations with North Vietnam near the end of the Johnson presidency.

SCHEER: Yeah, I would tell you this about Nixon. First of all, in any one of these things, you can do it with Obama in Iran, you could do–they’re always trying to score points and work their own positioning.

JAY: A lot of people died after the–.

SCHEER: I’m very well aware of that.

JAY: You know it better than I do.

SCHEER: Not only do I know, but I happened to also go to North Vietnam, and I saw the effects of the bombing, and I covered–I was in Vietnam originally and ’64-65 under the Democrats, and then I could see–. And by the way, I went back to Vietnam for Microsoft long after the war and did a very exhaustive survey of what had happened to Vietnam in the war. And I went to Cambodia. I was there during the coup. So I am not indifferent to the suffering of the Indochinese people. Three and a half million of them died. And I’m painfully aware of what a beautiful people they are and what great or different people the Khmer and the Vietnamese and the Laotians. And I traveled there. I spent a lot of time. And it’s one of the great tragedies of human history, because these were people who were swept into a Cold War that they had nothing to do with, and they had their own unique cultures that had withstood foreign invasions. And so I’m not minimizing that. I’m merely–you asked me, maybe it was stupid to do a revisionist history of things. I’m trying to tell you what motivated me. What motivated me–.

JAY: But was it also partly about going against conventional wisdom, either on the left or not?

SCHEER: I go out of curiosity. You know, I’ll give you an example. This morning–I don’t sleep all that much, so I woke up four or five o’clock this morning, and I read everything, you know, and all day long I’m reading or thinking or watching or something. And I like this. I’m interested, I’m interested in history, I’m interested in these issues, and they’re meaningful to me. So I see that our new–Ashton Carter, our new secretary of defense, gave a speech at Stanford. And in that speech–so I read it, because it was the Sid Drell Lecture. And I’ll tell you a story about Sid Drell, the physicist, in the course of this interview. But I was in the arms control center at Stanford that Sid Drell ran. And so I was interested in this speech, ’cause I’ve just done a book on Silicon Valley, on invasion of our privacy, what the internet companies do, their relation to the government. Well, here in this speech, Ashton Carter really laid out the connection between Silicon Valley and the Pentagon. He’s the head of the Pentagon. You know. So here I am at four or five in the morning. I say, damn it, he laid it out even clearer than some things in my book, you know, the relation between Google and DARPA and where the internet came from. And at the end of the speech, he says, you know, and we have this great precedent: this company now for over 15 years has been joining the Defense Department with Silicon Valley called in In-Q-Tel. Okay. In-Q-Tel is a company set up by the CIA which I describe in my book, and I haven’t gotten anyone to ask me a question about it. No one has responded, no reviewer, no–you know, really to examine what my book says about In-Q-Tel and how it set up about 250 Silicon Valley companies.

JAY: George Tenet’s involved in this?

SCHEER: Yes, George Tenet involved in it. And it goes back to before 9/11.

JAY: Alright. Since were jumping around, we’ll jump here.

SCHEER: Okay. So I’m going to just give an example of how I work and what I do. And so there I am at four or five in the morning. I try not to wake up my wife, so I have to actually go read this in the bathroom on my phone. And I’m reading this. You know. And I say, here’s In-Q–and he’s not ashamed about In-Q-Tel. He wants more. That’s the model. So that’s a CIA program. He says, the Defense Department’s now going to do it, putting seed money in. So here’s the military-industrial complex, which is now the military-intelligence complex, ’cause that’s where the real money is; it’s not in hardware; it’s in all cyber war and all this–.

JAY: Full-spectrum dominance.

SCHEER: Yeah. And his speech was a lot about cyberwarfare and the whole need to be active and what we need from the Valley. And it’s a recruiting pitch. And he brings up this program that I think is illegal on the face of it. It’s a–CIA’s not supposed to be involved in our domestic life, and here they’re setting up 250 companies. And among the companies is a company I discuss in my book, Palentier, which has seed money from the CIA. And for its first three years of existence, the real money came from guys who were in PayPal–you know, Peter Thiel and a few others. But the CIA put [incompr.] but [what] the CIA did, more important for this company that it was a part owner: it was its only customer for three years, and it allowed this Silicon Valley company, startup, to come into the CIA, play with all of our data and all of the world’s data for three years, and develop a data mining program, and have access to, you know, phone calls from the leader of Germany or Brazil or anybody in the world, develop a data mining software technology to the CIA’s satisfaction. But this is a private company, not accountable to anyone else. And now Palentier has contracts with all of our 17 intelligence agencies in the U.S. government; also has a contract with the Los Angeles Police Department, where I happen to live, the New Orleans Police Department, mining their data, using national data or international data with this. So when I write a book that says They Know Everything About You, I’m writing it in the shadow of the LA Police Department, which happens to be close to where I live.

JAY: Which has a long history of spying on people,–

SCHEER: It has a long history of spying on people.

JAY: –its own history.

SCHEER: And not only people, but me. I have gotten files from the LAPD.

JAY: For those people who are interested, we did a series with David Cay Johnston, I guess, it is that broke this story, right?

SCHEER: Who is a brilliant reporter.

JAY: Yeah. We have a series of interviews with him on The Real News where he talks about the spying of the LAPD on–not just here; they have people in Moscow and Havana. It was very bizarre. Alright. Let’s go back to one thing.

SCHEER: He’s a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter, and I’m really glad you call attention to his work, ’cause he’s one of–a really great journalist.

JAY: One thing you mentioned: Palentier has CIA seed money. Peter Thiel’s involved in this? ‘Cause Peter has a big reputation as being a libertarian, who one would think would not want to have a–.

SCHEER: One would think. I confronted Peter Thiele about this when he came to speak at USC, our journalism school. And I’m connected with the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. And I was disappointed that no one seemed to challenge this connection. So I waited for other people to do–most people wanted to know, how do you get jobs and how do you–you know, what–

JAY: How to get money from Peter.

SCHEER: –how do you get my from Peter Thiel. And you’re right. There’s a big contradiction, not just from Peter Thiel. First of all, there are very good, principled libertarians in Silicon Valley and elsewhere that have challenged the spying, including Ron Paul, for instance, and–.

JAY: Rand.

SCHEER: No.

JAY: Ron Paul. Yeah, Ron, certainly. Yeah.

SCHEER: Yeah, and then to some degree–.

JAY: I’m not so sure about Rand, but Ron certainly did.

SCHEER: Yeah. But, you know, the Electronic Frontier Foundation–there are plenty of good critics of the surveillance state who are libertarian. Peter Thiel is not one of them, and in fact he is very active in and owns this–one of the big owners of Palentier, is a company that, yes, its one ability–.

JAY: One moment. So Peter, you and I have met. We were on a panel together once in Silicon Valley. If you want to respond to this, you know how to get a hold of me. We’d be happy to interview you about it. Carry on.

SCHEER: Well, same for me. I’ve written about him in my book. But I raised–you can go on YouTube or somewhere and you’ll see I raised this question with Peter Thiel. I said, how can you, as a libertarian, be so involved with the CIA? And I brought the whole discussion up, and I said I thought it was a contradiction. And he conceded that there is some tension in his ideology. He didn’t say, oh, you’re ridiculous and you’re an idiot and goodbye and good luck. I mean, he–.

JAY: It’s good business.

SCHEER: Well, he treated it as–well, but you have it right through the whole business. You have–there’s a story again in today’s–morning, at four clock the morning, I’m reading about Amazon’s profitability. You know, Amazon’s had a hard time developing a profitable model. They have a lot of people use Amazon. But where is the money going to come from? Well, their most profitable sector now is cloud storage of information, which they seem to have most–a good chunk of the market, maybe 25, 30 percent, but they beat everybody in cloud. Well, one of their big profitable cloud programs is building a cloud for the CIA and the NSA. And Jeff Bezos, who is the owner now of The Washington Post, a paper that has some tradition of being critical of government, he’s now a partner of the CIA and the NSA and building their cloud capacity. And that is a source of significant profit. So he has a conflict of interest. I remember when I worked at the LA Times we had a scandal related to the paper because we had done an advertising supplement for the people building the new Staples sports center. And so we had a conflict: we’re benefiting from the ads, and yet we’re covering it. Well, think of the conflict The Washington Post now has, the paper, that their owner is in bed with the Pentagon, the CIA, and the NSA, and it’s a major source of profit. Now, he will say, I individually am the owner of The Washington Post, Amazon is a separate entity, but there’s definitely a conflict of interest. And so, anyway, I only bring this up about reading habits and what’s–drives you. I am curious. But let me get back to your biographical–.

JAY: Well, hang on. We’re going to keep these sort of in 20 minute segments or so, and we’re going to leave everybody hanging for the next segment. So please join us. Actually, let me just–to conclude, just to remind everybody, all of what we’re talking about results in what you call in your book the shutting down of democracy. And that’s what we’re going to continue to talk about as we weave Bob’s biography as we travel through this interview. So please join us for the continuation of Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

[simpay id=”15123″]

“Robert Scheer is an American left-wing journalist who has written for Ramparts, the Los Angeles Times, Playboy, Hustler Magazine, Truthdig, Scheerpost, and other publications, as well as having written many books. “