Remembering Salvador Allende’s speech at the UN in 1972 and the call of world nations for a New International Economic Order, Harris Gleckman explains how global corporations were more effective at setting the rules. Lynn Fries interviews Gleckman on GPEnewsdocs.

LYNN FRIES: Hello and welcome. I’m Lynn Fries, producer of Global Political Economy or GPEnewsdocs with guest Harris Gleckman.

A recent symposium marking the 50th anniversary of Salvador Allende’s speech at the UNGA in 1972 delved into the topic of “Corporate Power: Then and Now.”

In this segment, I invite our guest to expand on an argument he made at that symposium. Notably, that to build a stronger democratic multilateral system accountable to the public interest and committed to a sustainable planet we not only need to think about the narrative of where we want to go but we have to think about the institutional ways of making that happen.

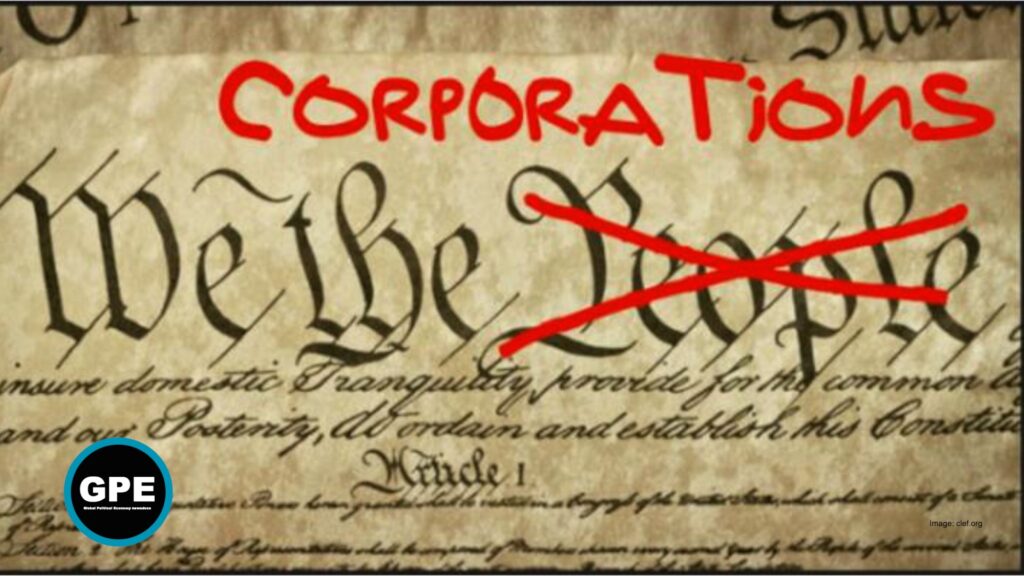

I should note our guest speaks from first hand experience of the ways in which corporate power undermined institutions set up in response to Allende’s appeal. And how into the present, corporate power has shaped or as some would say misshaped the international economic order where among other inequalities, transnational corporations but not citizens are protected under hard law at the international level.

Joining us from Massachusetts, Harris Gleckman is Senior Fellow at the Center for Governance and Sustainability, UMass-Boston. He’s Director of Benchmark Environmental Consulting and Board Member of the Foundation for Global Governance and Sustainability. And the author of Multistakeholder Governance and Democracy: A Global Challenge.

Among other distinctions and of particular relevance to today’s conversation, from the early ‘80s until it was shut down in 1992, Harris Gleckman was a staff member at the United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations. He served as chief of the UNCTC environment unit (1988-1992) and in this capacity prepared the benchmark survey and recommendations on sustainable development management for the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

I am delighted to welcome Harris Gleckman. Over to you. Harris.

HARRIS GLECKMAN: Thank you and thank you very much, Lynn for inviting me to join your series. The panel reflecting on Allende’s crucial role in initiating global conversations about the power of multinationals was a wonderful marker in history.

I want to pick up on your invitation to say what we really would like to see as a narrative for governing the international market and the institutions for doing that. I think that that at a minimum, we have a good model in theory which is what happens in the industrialized countries. And there are essentially five parts.

The first part is the state is intended to be the buffer between consumers and the industry; to be a buffer between the workers and the owners of industry. And the state has this intermediary role and an institutional role in balancing those sets of powers.

It sets up an administrative system to review mergers, to review technology issues, to review disclosure. It has an administrative structure.

It also has a series of organizations that explicitly say: here is what a product safety standard should look like. Here is what a medical device for testing efficiency should look like. Here is how workers should be protected in their workplace. It has a separate set of institutions to make all those activities happen.

It has a tax system which says this is the way in which the corporate world, in principle anyway, ought to be providing resources to meet, amongst other things, these needs.

And it has a court system.

When we move into the international space, we need all of those functions. And we need some additional ones because we have jurisdictional and political boundaries between countries. So those boundaries pushed by the corporate sector issue: They’ve demanded free movement of money going into the country, free movement of money going out, profits. They’ve demanded free movement of their technologies going in.

But we do not have free movement of people. And we do not have clarity about how to deal with liability and responsibility and obligations across borders. All of that needs to be part of a package. The best of the national practices and a whole other collection of institutional and conceptual features to regulate a global market.

But that’s not where we are. And there’s a lot of reasons why we’re not there. And amongst those that Allende flagged in his keynote address to the UNCTAD Session Three meeting in Santiago that initiated global attention to the need to figure out how to manage the international market.

Let me explain to you why we’re not where we ought to be. Out of Allende’s statement, a message of which he repeated in the General Assembly [the United Nations General Assembly], the Economic and Social Council brought together a group of eminent persons to say: President Allende, are you really right? Is it really necessary to do this?

And those eminent persons – a mixture of academics, labor, people from the corporate world, people from the legal profession – came with a resounding yes; we do need to do this. And they reported that to the Economic and Social Council who created two bodies. One, a standing body of governments to continue b the political aspects of this, the Commission on Transnational Corporations. And a staff called, as you referred to it, the Center on Transnational Corporations (most commonly used initials, UNCTC).

The Commission at its Second Session said to the staff, we’re giving you three major assignments. First is to address the normative legal basis for how to deal with transnationals in the international market. And please help us develop a Code of Conduct [on Transnational Corporations].

Second, they said: part of the reason President Allende’s appeal for assistance occurs in many, many countries of the developing world is because they need technical and legal and financial assistance in negotiating with multinationals and in writing their own laws. So the Center was asked to provide day in and day out technical assistance to developing countries on matters relating to transnational corporations.

And the third thing they asked of us was to do research and build a data base about the nature of transnational corporations. Because while certain elements were well known, many more had to be researched.

What was the response to this from the corporate world?

Part of it was supporting the Center on Transnational Corporations. Part, however, went to the OECD. And the OECD produced a competing set of standards which they called guidelines. So that introduced us to the first major tension about how we did not get to what needed to be an international arrangement for dealing with the international market.

The OECD explicitly said it’s guidelines. It’s voluntary: We will set some benchmarks, but it’s up to each company, each country, it’s going to be voluntary. This was the beginning of undermining an effort to build a constructive global system for managing an international market.

The narrative and the wording in negotiations around the Code of Conduct remained a tension point. Because when there are references to good accounting, to consumer protection, the concern of those in the corporate world was that these ideas might permeate at the national level in developing countries into law. And that, that in their view was a bad idea.

And so every section of the discussion of the Code of Conduct which might have been binding became a battle over the power of the narrative being moved into a legally binding system at least at the national level.

Lynn, you were referring to in terms of developing the criteria for sustainable development as a contribution to the 1992 Rio Conference on Environment and Development. This was an explicit request from the Economic and Social Council. And the Center convened many discussions with many advisors and produced this set of criteria for sustainable development management.

The pressure on that; sorry, I need to back up and say every idea that was in the criteria had a footnote which said some company in the world was actually doing that activity at that level of environmental and sustainable behavior. That wasn’t good enough.

As an example of the kind of pressure, the International Chamber of Commerce in Paris went to the Swedish government who had helped fund the work we were doing on the criteria and accounting standards. And the Chief negotiating delegate for the Swedish government in this process which was a very active country, was explicitly told, don’t incorporate this into the material.

And even more was told: don’t talk to the Center on Transnational Corporations. I can be honest with you, they basically did that. But as you understand, there was a conversation because I learned of that pressure brought through the International Chamber of Commerce through the Swedish government that constrained its contribution to the 1992 Rio Conference.

In 1992, something else happened. The Center on Transnational Corporations itself was shut down. That’s also a reflection of the political power of just trying to develop some guidance, some assistance to countries; some research was seen as too much of a challenge to parts of the corporate sector.

But that’s only a part of the story. Another part as I was indicating is that the idea of law and regulatory practices normally done at the national level in developed countries was moved into the area of volunteerism. Whatever standards there were, they had to be voluntary.

Another way in which this battle took place was over what for many it would be a mundane issue which is accounting standards. Part of accounting standards, so far as countries are concerned and so far as people are concerned, is the taxes that can be appropriately charged to international business. That turned accounting standards into a political fight.

The Center on Transnationals hosted an international standards of accounting and reporting body to give developing country accounting professionals and leaders a chance to meet and to recommend the standards they wanted. But the predominant role of setting the standards for the accounting profession worldwide is a voluntary set run through corporate organizations.

Let me just indicate how different these standards could be. Our colleague at the Center on Transnationals used to work in Asia for Exxon. And he would be asked by Exxon headquarters, did we make enough? How much did we make this year?

And his answer, which he repeated, says tell me, I have three different accounting standards I can use to answer your question. The US standard, the standard in the country, the internal Exxon standard, and he could have said, a fourth, the ISAR standard [International Standards of Accounting and Report]. Tell me which one you want, and then I can answer you the question, how much profits, which relates to the ability of the countries to do taxing.

Another area which is missing from what is the national practice is to set product safety standards for workers, for consumers. And here the UN was asked to produce a consolidated list of the rules and regulations about risks from chemicals and medical products.

A book early edition looked like this. As you can see, it was a substantial amount of work. This is a compendium of decisions made by independent countries so that it could be shared with other countries, both from a scientific point of view and an administrative point of view.

Well, you won’t be surprised this also got shut down. That means that the process which would be the equivalent at the national level of environmental protection agencies, occupational health and safety agencies that doesn’t have even a starting point in the way in which the corporate sector has that from happening, constrained the international level.

Another area is in the area of courts. In the developed world, you have a largely independent court system. You have administrative of courts. All designed to have the leverage to arbitrate facts and the power to order the implementation of decisions.

At the international level, there are no real courts of that nature. But what the corporate world has done is come up with a counter proposal, a counter structure, of the investor dispute settlement arbitration hearings [ISDS].

One of the key differences between that in a court is that the investor dispute settlement arena has an unusual criterion. The corporation has a platform to sue governments who enact health and safety environmental zoning rules, which might disrupt the profitability of the enterprise.

Again, the power of the corporate world on the, on the international level has blocked even the analogous institutions that operate regularly in the developed world. Two other areas where that is occurring; one is in governance.

In many developed countries, corporations, citizen groups, worker groups are encouraged to share their perspectives, to lobby the state, to say what the rules should be. At the international level, when Allende spoke and many years of the Center on Transnational’s and the Commission on Transnational’s life, the companies worked with their governments and the governments expressed certain views. Again, playing this moderating role but heavily influenced by corporate lobbying.

Subsequently, that wasn’t seen as adequate enough and corporations wanted to become at the table in setting rules and standards. And one of the ways in which they did this is create another form of institution called a multistakeholder body.

These multistakeholder bodies exist in the area of setting product standards: The Marine Stewardship Council, the Forest Stewardship Council. In effect, these are the analogs to the national bodies. But now the firms involved are on the governance of these bodies.

The firms or their spokesperson organizations wanted to be in the policy debate through multistakeholder forums. And this is now a direction which is, for the last 15 years now, a push from the World Economic Forum.

And unfortunately, to be candid with you, one which the current Secretary General [the United Nations Secretary General, Antonio Guterres] has largely agreed to. And has a partnership agreement with the World Economic Forum to open the door more for these multistakeholder bodies which brings the corporation into the governance process.

The current Secretary General has proposed as part of going forward after the 75 years of the United Nations: Our Common Agenda is his report. That report says that six other multistakeholder bodies should be created to deal with global policy issues. And it’s also telling that the Secretary General made no recommendations for governments to negotiate new international agreements.

So another way in which the pressure from the corporate world has influenced the governance of the market is that the firms now are seeking and have got a seat at the table for a number of the standard setting practices and policy making in global governance.

And I want to share one other which is quite central to this discussion. And it’s quite central to the discussion in the climate discussions and in the sustainability discussions.

The sustainable development goals are negotiated between governments. But those governments who have the capacity and the money for doing it didn’t put up the money, are not putting up the money. Because they’re leaving the door open for corporate philanthropies and individual firms to decide how to fund the future needs.

And so corporate philanthropy power is very serious. We just had a very dramatic example of that political leverage through funding in the institution set up to deal with COVID – to fund the vaccine access for many developing countries – called COVAX.

COVAX did not meet its goals. COVAX was a multistakeholder body. But, two weeks ago, one of the funders of COVAX, it’s called GAVI, the Global Alliance on Vaccine Initiative, said: It’s not working. We’re going to stop funding it.

GAVI is supported largely and centrally by the Gates Foundation. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization is saying very clearly, COVID is still a problem in the developing world and other parts of the world, and we need money. But the corporate funders have said that’s enough.

Unfortunately, also by the current Secretary General’s advice, many countries who might have previously given their donations to the World Health Assembly to do vaccines for COVID, instead, we’re encouraged to give their money to COVAX. And now COVAX is collapsing.

Now I mention [all] that as the six different ways in which what ought to be the system for governing multinationals and transnationals has been undermined in the last 30 years.

So where can we pick up some of Allende’s enthusiasm and the enthusiasm and commitment of many other people around the world going forward? Let me offer five possible routes for maintaining and pushing forth further on this.

First is the need to keep transnationals [transnational corporations] out of the governing process of international affairs. At the level of products, this is actually being done in the case of tobacco and infant formula. Where the treaties explicitly say that firms in that industry cannot be in the room, cannot participate, cannot contribute. Because the space is for governments to figure out how to make decisions.

But that’s not what’s happening in climate. In climate, the corporations were all over the recent Conference of Parties in Egypt (COP 27). They struck an agreement with the Egyptian government, Coca-Cola, to fund part of the cost of the COP. They held sales exhibitions; oil and gas companies could put up tents to show how good they are.

A new wall has to be built to reassert the space for governments to meet without the corporate world interfering in setting what should be the rules for the global market.

A second area is some work under the United Nations Human Rights Council where they’re negotiating a binding treaty dealing with the issue of cross border liabilities. This is one of the areas where on the international market, there’s an enormous hole. And this gap prevents those who may cause problems from having a court room where those who have been harmed can make their case and that settlements can be enforced.

So, there’s an effort for a binding treaty for the Human Rights Council. And that work is an area which would be very helpful for many people to be aware of and to join that activity in Geneva.

A third area is to keep raising the attention the way multistakeholder bodies provide a frame, an institutional space for the corporations to enter public decision making. These are presented as if we now got everybody in the room. But everybody in the room has been ones which the f unders or the powerful actors have selected. And governments are treated as if they are equal to academics or to the corporate world or civil society.

This forum does not have a base in any concept of democracy. And that’s an area, you know, Lynn that I’ve been writing on for a while.

Another direction, a fourth, is to begin envisioning what would the next commission on transnational corporations, the next Center on Transnational Corporations, what would they look like? In terms of the narrative, their assignment, their institutional relations, planning how to build the next foothold. To begin to construct the kind of ways in which we ought to be able t o govern the international market.

And my last suggestion is the toughest one, as we need to figure out what is, what we really would like to scale up democracy at a global level. And how does this fit well with regulating dominant forces in the market?

And this is a tough question right now; our basic principle is enshrined in the ‘one country one vote’. It doesn’t take a lot of quick of study to realize that there are a lot of small countries in the world population wise, and there are a number of very large countries in the world population wise.

But at most democracies are based on individuals. And we haven’t got that kind of system at the international level. Do we want it? That’s one of the questions about envisioning what one would want out of a whole global governance system.

A key part of that would be how to make sure that the right balance is maintained between the international firms and workers who are employed directly or indirectly by them; between international firms and the products and services that they provide; and between international firms and the natural resources that they are using. Those features of a global oversight of a market are essential. Thank you, Lynn.

FRIES: With those thoughts, we are going to leave it here for now. Thank you, Harris. And from Geneva, Switzerland thank you for joining us in this segment of GPEnewsdocs with Harris Gleckman.

Harris Gleckman is Senior Fellow at the Center for Governance and Sustainability, UMass-Boston and Director of Benchmark Environmental Consulting. He is Board Member of the Foundation for Global Governance and Sustainability. He was a staff member of the UN Centre on Transnational Corporations and head of the NY office of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. He is the author of Multistakeholder Governance and Democracy: A Global Challenge.

[powerpress]

[simpay id=”15123″]

“Harris Gleckman is a senior fellow at the Center for Governance and Sustainability at the University of Massachusetts Boston and Director of Benchmark Environmental Consulting. Gleckman has a Ph.D. in Sociology from Brandeis University. He was a staff member of the UN Centre on Transnational Corporations, head of the NY office of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, and an early member of the staff for the 2002 Monterey Conference on Financing for Development.”