This interview was originally published July 5, 2015. On Reality Asserts Itself, Robert Scheer says you get drunk on the power of this culture and its military, its wealth, and you can become incredibly destructive. And we have been incredibly destructive.

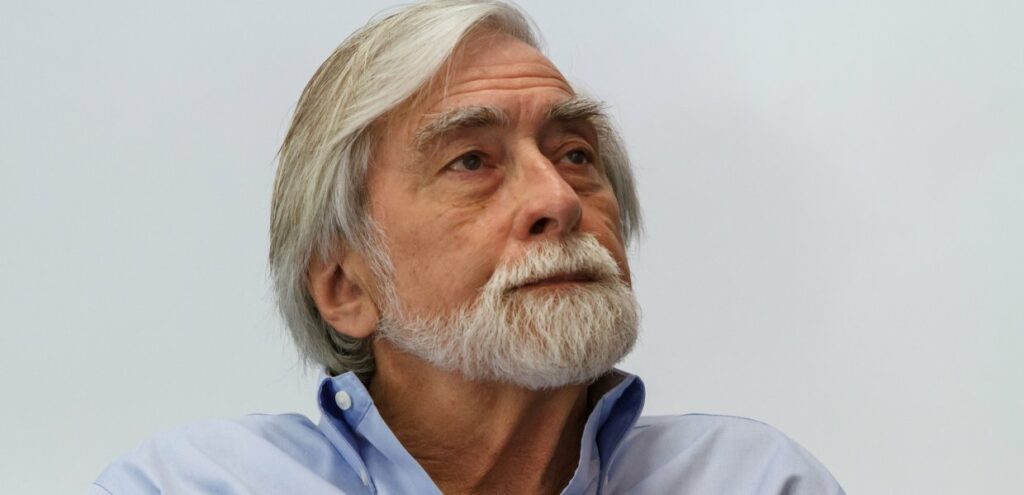

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay. And we’re continuing our series of interviews with Bob Scheer, the editor-in-chief of Truthdig, the multi Webby Award winning news site. Thanks for joining us again.

PROF. ROBERT SCHEER, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: And we are a multi Webby Award winning news site.

JAY: I know you are. I said it so many times I have to–. So you’re 79.

SCHEER: Yeah. JAY: You’re going to be 80 soon. You don’t seem–.

SCHEER: I’ve got another year [crosstalk]

JAY: Another year. Alright. You don’t seem to, like, have stopped at all or slowed down much. What keeps you going?

SCHEER: Well, it’s funny, ’cause my wife asks that. People ask me that question all the time. And I say, if I didn’t have outlets, I would still have outrage. I would still have concern. I would tear up. I care. You know, we were stopped by some guy across the street asking you for money. My initial response was to stiff him. I’m asked for money all the time. You gave the guy money.

JAY: No I didn’t. I made you give the guy. I didn’t have any.

SCHEER: You didn’t make me. So, okay, we gave the guy money.

JAY: Yeah.

SCHEER: I can’t be indifferent to that person. I don’t know what–my upbringing, my background, being human, these are not, to me, problems to be thought about intellectually or figure out how to win a chess match or how can you accomplish this. I don’t know. Maybe it’s my upbringing, but I always had the idea that everybody matters. And I was not raised in an elite environment. My parents were garment workers, and I knew they mattered, I knew their friends mattered, I knew the people in my neighborhood mattered. And they didn’t make a lot of money. They worked hard. And some fell off and became what we used to call bums. You know, my father would take me down the bowery, show me people who were waiting, lined up to get food. You know, I was a kid during the Depression. And I never–no one around me, no one ever gave me a reason to think that these people were not equal to me and to anyone else. I never–I was always raised with the idea there was an inherent value to human life. And I think–and it certainly was not based on religion. I think it was enhanced by not being religious. I had to find meaning in the secular life. You know, I couldn’t be waiting for another life. And I couldn’t find it just in scripture or something. My parents had both basically rebelled against the life of scripture. They saw its downside. My father was crushed by seeing what happened to Christian Germany. He’d started out raised as a Lutheran and a law-and-order people, hard-working, good attitude, and he saw them descend into barbarism. And he was here when that happened, but this was the big struggle in his life. How did his people, the good Germans, become such maniacs and kill people, people like my mother, who was Jewish. You know. And then my mother always had a real strong universalist sense of being Jewish. She didn’t think the goyim were inferior in any way, even when they were anti-Semitic, which she’d grown up with in Russia, you know, the tsar, and then later the Bolsheviks, and she’d seen the brutality, she’d seen pogroms. Two of her sisters had been killed in pogroms. And yet my mother always believed everyone had importance in life. And I think I told you this story: when AIDS came along, there’s my mother with Parkinson’s and suffering and everything, tells me I have to write about AIDS, that people are hurting. You know. And so there was always a sense that what gave life meeting was your concern about others.

JAY: You mentioned Germany descending into barbarism. It didn’t take very long in terms of the number of years. Do you think that can happen here?

SCHEER: I not only think–.

JAY: Or do you think it’s happening here?

SCHEER: No, I don’t think it’s happening here. But I do think it can happen here. I think–and one of the really disappointing things about Germany for me, ’cause I’ve gone back there quite a few times, found my father’s brother and all that sort of thing–he was nice guy, a good guy–is how they can return to normalcy so quickly, almost like it didn’t happen. You know. But then again, I’ve seen other manifestations of it. I went to the American South in the 1960s and was dumbfounded by segregation. Dumbfounded. You know, the separate drinking fountains. I mean, what’s segregation? I mean, suddenly everybody forgot about it. Next thing I knew, I’m interviewing Jimmy Carter and the new South and the old South. And I used to say cynically the new South is the old South plus air-conditioning. You know. But what happened to those attitudes? They didn’t just die out. They persisted. People had to struggle with them. We have racism now.

JAY: You see the murders of young black men, the mass incarceration. This is barbaric.

SCHEER: Well, but it’s also based on the idea that their lives don’t matter as much as other lives. So Jewish lives didn’t matter as much as Lutheran lives, you know, or maybe they were connected to the devil or something. Who knows. They were inferior people. And so those attitudes persist internationally. And they always offended me. And when I realized there were things I could do about it at a quite early age–I remember my uncle Edward took me to picket in Ebbets Field for them to hire Negro athletes. Well, you could do something about it. You can raise your voice. My parents were union organizers. They thought they could improve their condition. And so I always had the idea that people can make history and that we had an obligation to make history to the best that we could. And my expectations were really quite low when I think about it, by the standards that you’re summonsing up, of make a revolution, change. No. You know, the standards that I was up is to be able to have a union for garment workers or have an eight-hour workday or get the weekend off, get the vote in the South, for example. You know. And those were the causes that I was picketing with. I remember when I went to graduate school, I first went to Berkeley, we’d picket Woolworth and Kresge every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. That was part of going to graduate school. We picketed Auto Row in San Francisco. We picketed the Sheraton Palace Hotel ’cause they wouldn’t allow people of color to work the front desk. You know. San Francisco, for God’s sake. You know? And then, so, later we were fighting about things like the right of farmworkers or the right of immigrants or the right of gay people or women’s rights, equal pay. So to my mind it very clearly was better to struggle over these things and celebrate what might seem small victories, but they added up. And I guess my optimism is that I’ve seen quite a bit of positive change in this world. You know? I mean, I’ve seen in many ways things get better. You know. And I think there’s other people who don’t see it that way. They think things are getting worse. But, I mean, globally we sure have a lot of people who have been given opportunities that they didn’t have even ten, 15 years ago. Right? I mean, not everywhere and not evenly, but–.

JAY: We did. It’s getting worse now. There was a time when there was a somewhat lowering of poverty and starvation, but the numbers are actually coming back the other way again.

SCHEER: Let me challenge a basic thing that’s going on here.

JAY: Yeah.

SCHEER: Maybe this will help. I, maybe ’cause I grew up among immigrants–you know, where I grew up in the Bronx, I mean, foreign languages were everywhere and everybody was coming from some other place and had some story. And some of them had arrived just months earlier or weeks earlier, and you’d hear tales of the rest of the world and everything. And I grew up loathing–loathing–an America-centric view of the world. And I think that’s at the heart of a lot of concern that some of my friends have. They see all of change having to take place here. They see the American condition as the critical one for the human experience. I don’t have that view. I’m optimistic that America will become a better player in the world. But I think that requires first of all recognizing that we are not the all-powerful, all-knowing center of it all. We’ve had a good run. We’re a good people. We’ve got a nice piece of real estate here, good climate, good place to grow stuff and mine stuff and everything. But we’re not the source of the world’s wisdom. You know, we’ve made an important contribution. And the future going forth, I suspect our contribution will be less dramatic, not as singular a contribution. We came out of World War II with the only economy that was stronger rather than weaker because of the war. We could produce a lot of products that the rest of the world wanted. You know. Or we had a lot of options other people didn’t have. We’ve all through my life attracted a very large number of hard-working, skilled, smart people who helped lift this economy. But I don’t think that’s going to be the case going forward in quite the same dramatic way. I notice with our students at the university that many of the Chinese now don’t want to get papers to stay here. That used to be the big thing if you came from India or China. You know, how do you get a job?

JAY: You’re suggesting something we argued about in a previous segment, a kind of rationality I just do not see in this system, in this country. I don’t see the predominant opinion, sections of the elite, both ownership and political, who are willing to give up this role of being the dominant power.

SCHEER: Oh, it’ll be given up for them.

JAY: Well, they’re going to give it up kicking and screaming, which means–.

SCHEER: I don’t think so, because–. Okay. So let me meet that–.

JAY: This isn’t going to be like England after World War II.

SCHEER: This is a good way to sort of tie up our–all the differences in optimism, pessimism, and so forth. I don’t think we get to make that decision. You know, it’s like the people on that island, England, they may think they’re still the center of the world, but they’re not. And the French are not the center of the world. And this is a good thing. You don’t have to be the center of the world to be happy. You know, we have a lot of problems to deal with. We have to figure out who we are, how does the melting pot work in the modern age, what is our basis of unity here as a people. You know. And that’s fine. But we’re not the be-all and end-all for the whole human experience. You know. And it’s sick to think that we are or need to be. And I think increasingly with this unified world–and it is increasingly unified–we’ll learn from others, we’ll see things that work, you know, we’ll have more of a sense of our own vulnerabilities and limitations, unless–and what you’re pointing your finger at is a real threat–we use our excessive military power in a kind of a temper tantrum to have our way. That’s a real danger. And, yes, we have jingoistic elements in our own country that want to assert just such a temper tantrum, bomb them. I mean, even Hillary Clinton at one point said we would obliterate the Iranian people if they attacked Israel. Now, it would be terrible if the Iranian people attack any other country, but where do we get the right to obliterate anybody? You know? Where do we get the right to make such profound judgments about–.

JAY: Even this position President Obama takes, this idea, in terms of the supposed nuclear program in Iran–he says all options are on the table. That means one of the options is a war crime, because to bomb Iran because maybe they might have a nuclear weapons program, that would be a war crime.

SCHEER: Right. So my concern is not human progress. I think people in this world are going to keep doing what we and others have always been doing, which is try to find meaning in life. And, hopefully, finding meaning in life, whether you’re living in Nepal or you’re living in Scotland or so forth, is something that will be approached by different people drawing on their history, their religions, their ethnic origins, and so forth to come up with different ways of living, different ways of solving these problems. I don’t think they’re going to look as much to the U.S. for all of their answers as maybe they have, because I don’t think our films and our music and everything will be so dominant in the world. I mean, already we’re seeing that people in India and China and smaller countries can come up with their own cultural responses to technology and the meaning of life and so forth. I think a lot is up for grabs. I think the hold of religions will recede, so a lot of the ethics, questions that have been solved by religions for many people will have to be answered in new and fresher ways. There’ll be more thought about what is our connection with each other. But I don’t know. There’s a tendency–you ask about my age–there’s a tendency to think that you’ve seen it all–or I don’t think we’ve seen anything, frankly. You know. But I suspect that’s true of almost every 79-year-old in the history of the world, right? Oh, I saw all of that. But you saw one period of history from one vantage point with one set of experiences. So who’s to say that the next 79 years aren’t going to be more interesting? I would expect they’d be a lot more interesting. I mean, we’ll probably extend life and all sorts of ways. We will have–already we can talk to each other. We have instant translation. We can read each other’s writings very quickly now on the computer. I can pull up a Chinese newspaper–I struggled like crazy to learn Mandarin at Berkeley in graduate school. Now I don’t have to do that. You know, I’m not denying there’s some value in doing it, but you can read the Chinese press, they can read our books and press without going through all that. So I don’t know what’s going to happen for the next to 79 years, but I suspect that it there’ll be a lot of good things happening. And there’s–we already see–you know, there’s so much more environmental awareness. I mean, just take, okay, something I just alluded to before. You know, let’s take this question of gay rights. Okay? We’ve seen an incredible advance in gay rights in, I don’t know, ten years, I mean, you know, marriage accepted, and everywhere, not just in Greenwich Village, but all over the place.

JAY: But that’s something–.

SCHEER: That involves breaking the hold of some traditional religion.

JAY: Yeah.

SCHEER: That involves really seeing the world from somebody else’s eyes, very different than yours, seen the family from someone else’s eyes, very different. It involves a level of tolerance and compassion that I didn’t see in this country. You talk about the ’60s. Stonewall, the great demonstration for gay rights, happened after the ’60s.

JAY: But it’s something that the system can assimilate without threatening who owns stuff and who has power. In fact, a lot of wealthy white people, particularly white men who are gay, had a lot of political influence. And, yeah, it showed changing attitudes. But chronic poverty, chronic racism–you know, we’re in Baltimore where people–not just one guy’s been killed by cops, but many have been beaten and many of them killed–this profound rot within the society goes on for decades and decades and decades.

SCHEER: Why don’t we talk about race? White people can talk about race.

JAY: Yeah, of course. We talk about it all the time.

SCHEER: No, I mean, why just make it a marginal issue?

JAY: I’m not suggesting it’s marginal at all. I’m saying the issue of gay rights is something–.

SCHEER: I meant for the purpose of this discussion. Okay, what’s the difference between gay rights, which, of course, there are many gay black people and brown people and so forth, but what makes the difference? And you’re right. For white gays, you couldn’t ghettoize the problem once people started coming out. As long as you can make it a ghetto issue, as long as people were in the closet, you could scapegoat gays, you could, say, make very negative images–they were all child molesters, they were all dysfunctional, and it’s a mental illness, [incompr.] all was said about gays, including by The New York Times. At the time of Stonewall, The New York Times had editorials bemoaning the presence of gays. Right? And some of those people were gay, but they weren’t out of the closet. So what happened in the gay movement is that once gays came out–and AIDS had a lot to do with it, the Rock Hudson example, and so forth–once it came out, hey, you know, it’s my son–in my case it is; I have a gay son–it’s, you know, your minister or it’s–right, it’s your neighbor, it’s your school teacher. And then it became impossible, I would argue, for the culture to stigmatize, to denigrate, you know, to marginalize, ’cause the difference is that with a racial minority, there’s a badge.

JAY: Well, that’s one difference.

SCHEER: It’s a big difference.

JAY: It’s big difference.

SCHEER: It’s a big difference,–

JAY: It’s a big difference.

SCHEER: –because, as my dean, who happens to come from–Ernest Wilson and his family goes back, I think, three generations at Harvard, and they go back to very respectable lives, but he will point out that his sons–and he himself–are stopped by the police, profiled, and have that same harassment no matter the degrees, no matter how they’re dressed, or anything else. So that label is then able to use to stigmatize people. But also the fact is there’s a historic legacy of oppression for black people in this country that we–we meaning the mainstream society–have wanted to minimize. You know. The experience with segregation, and before that, obviously, slavery, was such a profoundly deforming experience, and the way the rest of society handled it, after slavery and then after segregation, was to minimize it. You know. But I remember Willie Brown, who went on to become the mayor of San Francisco, and before that was the most–at one point the most powerful person in the California legislature–. And I interviewed him for the L.A. Times at one point. And I remember Willie Brown–this is before his full rise–he was talking about growing up in Mineola, Texas, and walking down the street, and some white young kids, teenagers, are coming. His father would get off the sidewalk, the raised sidewalk, and go into the gutter to make room for them. You know. He would talk about being up in the crow’s nest of the movie theater but not down with the white people. And, you know, you don’t–a society that wants to deal with that has to confront it, and in a very serious way. We have never done that. We assumed, oh, the court made this decision or this–oh, now get over it. Get over it.

JAY: Alright. Final word to young people watching this piece.

SCHEER: History matters. And you have to understand the history of other people as well as yourself. You know. If you don’t do that, you will not grow in your own understanding. You could be talking about the Palestinians and the Israelis. You talk about black, white, brown. If you want to understand someone who’s coming from Oaxaca and spent the first ten years of their life there and they’re now living in L.A., you’d better understand that’s not the same experience that’s coming from, you know, Santa Monica and having had a white privileged life. You’ve got to understand where people are coming from in China or India and of different classes, different backgrounds, and so forth. And history has a hold on people.

JAY: So give up American-centric view of the world.

SCHEER: It’s really critical. The arrogance of our culture is numbing. It leads to not just insensitivity; it leads to callousness. It leads to brutality. If you want to understand Abu Ghraib, if you want to understand what we did in Guantanamo, you want to understand–I mean, for me, the most compelling experience of my life was to be in Vietnam and to have witnessed, in the North particularly, the effect of the carpet bombing, the napalming–I mean, it’s just incredible–in the South, just what we were doing to a people who–now, right, you’ve got Vietnamese all over the place. You go have some pho at some restaurant, and you don’t say to yourself, oh, I had the right to napalm that person who just served me the pho, I had the right to send or pay for, as a taxpayer, and support a government that sent airplanes over there and just bombed people like that, right, who had no capacity to shoot down this airplane. Right? No military threat to our homeland. And yet we could do that. That’s a sickness in any culture. But when you come from the most powerful country in the world that is also the most arrogant because of its claim to be the depository of human freedom, etc., it makes for–it’s a toxic cocktail. You get drunk on the power of this culture and its military, its wealth, and you can become incredibly destructive. And we have been incredibly destructive.

JAY: Alright. Thanks for joining us, Bob. And thank you for joining us on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

[simpay id=”15123″]

“Robert Scheer (born April 4, 1936) is an American left-wing journalist who has written for Ramparts, the Los Angeles Times, Playboy, Hustler Magazine, Truthdig, Scheerpost, and other publications, as well as having written many books.”