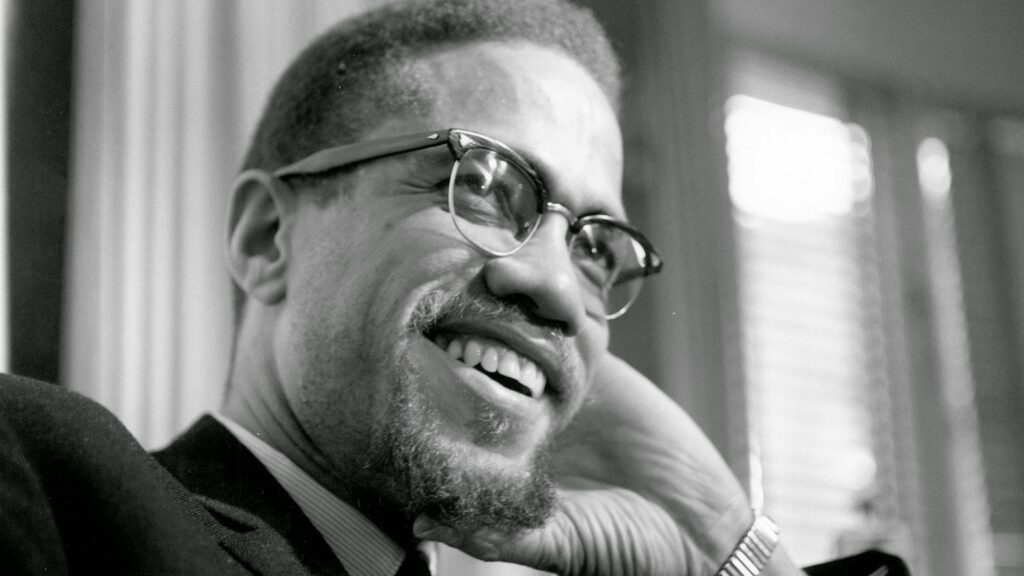

This interview was originally published on March 4, 2015. On Reality Asserts Itself, Mr. Franklin says that after growing up in the projects of Brooklyn, reading the autobiography of Malcolm X changed his life.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. And welcome to Reality Asserts Itself. I’m Paul Jay. The question of the relationship of the African-American movement or the new militant movement that’s emerged in places like Ferguson and other places across the country, the relationship of that movement to the overall people’s movement is sort of a burning question facing those who want to change the world and change American society. So that’s the overarching theme of this Reality Asserts Itself. And joining us is someone who’s grappling with all of this and now in the studio, Kamau Franklin. He currently serves as the southern regional director of the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker social justice organization. He’s a leading member of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, where he worked on various issues, including youth organizing and development and police misconduct and such. He also briefly served as an attorney for a man he says was wrongly convicted of assassinating Malcolm X. He’s also the former cochair of the National Conference of Black Lawyers, a member of the executive committee of the National Lawyers Guild, and the former legal program director of the New York City Police Watch, which established the first watchdog accountability organization of its kind in New York. Thanks for joining us.

KAMAU FRANKLIN, ATTORNEY AND ACTIVIST: Thanks for having me.

JAY: So, as you may know and as viewers of Real News and Reality Asserts Itself knows, we usually start with a personal back story, why a person thinks what they think. And then we get into some of the issues. And that’s what we’re going to do. So start from the beginning, where you were born, the kind of political culture you grew up in.

FRANKLIN: I was born in Brooklyn, New York, working-class family.

JAY: Nineteen sixty-seven.

FRANKLIN: Nineteen sixty-seven I was born, me, my mother, and my sister. My mother’s from Charleston, South Carolina. She moved to New York in 1960. So she experienced some of the civil rights movement firsthand, being born in Charleston, South Carolina, during Jim Crow years. And she had a tremendous influence, just telling stories about the Old South, in terms of the sort of politics of my household, what they were, of politics in my household. She was a nurse early on, a–.

JAY: Stories? Like what? What were the [crosstalk]

FRANKLIN: Well, I mean, my mother to this day has a scar on her back from when she played in a whites-only playground, and her and her friends, they were being chased out of the playground, and she was too slow, and she got hit in the back by a cop with a billy club. And so it busted her back wide open. And so she would tell us that. She showed us the scar. It’s sort of a large, raised bump on her back. Her mother working in white folks’ homes. The struggles of her family just surviving economically. Sort of the interplay between her and her stepfather. So she would–my mother’s an amazing woman, ’cause she would tell us these stories, but yet some of them sad, depressing, tragic. But she would do it in such a way that sort of brought in sort of a comedic element and just made things sort of funny and just exposed to us some of the rawness and realness of life in the South, but in a way that made us feel that she was somebody who survived it well. Right?

JAY: Did she get involved at all in the civil rights movement?

FRANKLIN: She got involved in civil rights. She talks about marching. When she tells the stories these days, it’s more that she was sort of standing on stage with Dr. King at the March on Washington. But I’m going to give her a little bit on that, ’cause she–yeah, she did get involved nominally. She moved up here in the 1960s, I think, about 1960. And my mother has an interesting sort of racial viewpoint of how the world works, which also shaped by politics. So my mother’s a dark-skinned black woman, and she–I guess my sister, her father is a lighter-skinned black man. My sister is a lighter-skinned black woman. And my father was white. And so my mother, in terms of her life choices, chose–’cause she–some of the people that she would have children with because she thought it would make it easier for us to sort of survive in America by being lighter-skinned.

JAY: So it was actually a deliberate choice to have a white partner.

FRANKLIN: And yeah. Yeah. And so, I mean, I believe she would tell stories and she sort of loved him and they were close, but she definitely remarks on that. And it’s this–growing up, where we grew up, too–like, I somewhat was a sort of project nerd. So I grew up in Albany Houses in Brooklyn for, like, 40 years of my sort of 46, 47 years on the planet. And just to see the neighborhood and the community that we grew up in and what my mother thought she was doing to make it better for us and how that stems from the attitudes that people have in the South.

JAY: And do you think it did?

FRANKLIN: I think there are probably some things about it that definitely gave me better life choices than others. I mean, I think that’s how America works. Like, the lighter skinned you are, the more opportunities you have, the more times people give you the benefit of the doubt than they do other folks. So I definitely think it has some role or some way of improving life chances, right, that sometimes people don’t measure. And sometimes they do. But I definitely think it has some role in some of the ways in which my life opportunities have presented themselves at times. Yeah, definitely.

JAY: And what was her politics in terms of did she vote? What did she think of the various parties?

FRANKLIN: My mother was a liberal Democrat, to a militant when need be. So she voted sort of democratic across probably most her life. She talks lovingly of John Kennedy, as most older black folks do. We had a picture of Kennedy, Dr. King, and Abraham Lincoln in our house back in the early ’70s. So I remember that. So that kind of stuff played–so she didn’t stress or strive about politics in terms of everyday discussion, but you can tell she had a sort of natural distrust around sort of the system and how it worked and talked about things as the system, a natural distrust of working close to and next to white people at the same time as feeling that by being close to white folks you increased your chances of life success. So there’s all this sort of interplay in terms of her own thinking.

JAY: So a mix of civil rights and find a way to assimilate and get along.

FRANKLIN: Oh, yeah. And she would say a bunch of times to us that she followed Dr. King, but when she got to New York, she was sort of drawn to Malcolm X, and she believed that if somebody hit you, you hit them back. My mother’s a fierce woman. Like, she’s older now, but one of my earliest childhood memories is my mother fighting her boyfriend and throwing him out of the house. So she was not one to take anybody’s mess. She taught as well. And in a lot of ways, too, my mother had made sure that even in the sort of the circumstances in which we grew up in, she did her best to make sure that we had food on the table, and she did her best to make sure–.

JAY: What did she do?

FRANKLIN: She was a nurse, and then she lost her job, and we moved to Albany Houses–still in Brooklyn. So probably I was ten when we moved to the projects and lived there, probably up until about four or five years ago.

JAY: Is your father in the picture?

FRANKLIN: No, my father–probably they broke up in 1968. And my mother after–.

JAY: Just after you’re born.

FRANKLIN: Just after I was born, yeah. So I don’t have any pictures or recollection or anything that sort of connects me to my father. And the same thing is true for my sister. Once my mother, my social relationships were over, my mother didn’t keep a lot of mementos or keepsakes about those relationships. And I was going to also say, after she lost her job as a nurse, we were on public assistance. So I also grew up from 1976 to 1977 on public assistance. So you don’t have food stamps these days. They have cars, I guess, BET–BTE cars, or whatever they call them, they give out. But back in the day I remember the funny money, we used to call it, that you would go to the store with and purchase groceries and milk and all the rest of it and government cheese. I mean, we experienced all of that through growing up in the ’70s and ’80s in Brooklyn. Yeah.

JAY: So you grew up in the projects. What is that like? Is it as violent as people–or was it as violent as sort of the stereotypes?

FRANKLIN: No. I mean, I think it’s like anything. Sometimes people develop community, right? So it’s a community based on survival, it’s a community based on needs. Neighbors are sometimes good to each other. They watch out for each other. And I think there’s also times where people living that packed and close together, there’s fights, there’s arguments that lead to destructive behavior. But I think any time you put a large amount of folks together sort of in these sort of compacted or constricted neighborhoods without a lot of resources, it’s inevitable that that kind of thing is going to happen. I was taught early and I learned early to keep my head down, to keep quiet in a lot of ways. I feel–I was saying I was sort of a project nerd, I guess, in terms of my activities. My mother made sure I was upstairs at nightfall. She made sure she knew what was going on with me. And any kind of little bit of trouble I would get into, it wasn’t serious enough for her to be that worried about it. And I was kind of a mama’s boy in a lot of ways. She was my best friend for a lot of my growing-up years.

JAY: So you listened.

FRANKLIN: I did listen. My mother had the capacity to smoke in my face and tell me not to smoke. And that lesson got through to me. So there was a lot of listening, and there was consequences if you did not listen, which I did not want to experience. So, yes, I was a good listener.

JAY: Now, I know you, I’ve gotten to know you, and I know your biography. You grew up with a real social consciousness, and as we get into your biography. But this choosing a white partner, partly so your kid can get ahead, that’s kind of, you know, I’m going to set you up for a career, not necessarily social consciousness.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. I think it was–well, the social consciousness, in a sense of the time period that they came out of, it was omnipresent. Those things were a way of looking at the world, looking at the world of what whiteness means in America and what it means for your child to get ahead.

JAY: No, I’m talking about get ahead individually, or get ahead as somewhat who’s–.

FRANKLIN: Individually.

JAY: Yeah.

FRANKLIN: Get ahead. Oh, yeah, definitely.

JAY: Yeah.

FRANKLIN: Definitely. It was, in a sense, a way of trying to set up a career, a sense of trying to set up an advantage for your child. And any advantage, to someone who comes from a poor upbringing, she felt that she needed to try to give her child. I mean, I think it’s remarkable in some ways that someone who I feel is as lucid as my mother is on a lot of topics and as honest as she is about a lot of topics, when she made these kind of choices in her life, she did it because she thought that somehow the racial dynamics matter to the point of–that–her love interests or her life choices, like, that mattered also.

JAY: So you’re now ten, 11, 12. You’re in the projects in Brooklyn. And you’re good in school.

FRANKLIN: I’m decent. I’m a little lazy in school. I get over it because I’m a, relatively speaking, smart kid.

JAY: You’re a quick study.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. But I wanted to be one of the cool kids. I had a fast mouth, but nothing else was fast for me. I couldn’t duck punches that well. But I did enough to get by. Like, I wasn’t even sure I was going to college, actually, when I graduated from high school. I decided–actually, me and a friend of mine, named Tyrone Sumpter, from high school, we had both decided not to go to college. We wanted to be men and get jobs.

JAY: And how political are you?

FRANKLIN: At that age, not political at all.

JAY: Not all.

FRANKLIN: No. I mean, at that age I understood racial dynamics and race relations, but there was nothing about being 17 or 18 years old that led to anything political for me at that particular time. I think in the background, some of my mother’s stories helped me understand the civil rights movement. They made me interested in documentaries at the time. But I wasn’t anybody who was active in any sort of constructive sense around sort of politics or social justice or anything like that.

JAY: Now, I know from reading things you’ve written, a big moment for you is when you read the autobiography of Malcolm X.

FRANKLIN: Yes.

JAY: When is that? And what is the impact on you?

FRANKLIN: Well, I was going to say really quickly. So a friend of mine–and we decided not to go to college. And we both got jobs. And he got killed. And that was something that drove me to go to school. And it was actually through college.

JAY: He got killed how?

FRANKLIN: He got shot. He was outside. Some guy was coming by with his girlfriend. And him and a bunch of friends were making fun of the dude. The dude went upstairs, got a gun, came back downstairs, and started shooting randomly, and he actually got shot in the head and was killed, which I learned from another friend who I ran into, and he was like, did you hear about Tyrone? So that was one of those sort of waking up moments of, like, what am I doing?

JAY: What year is it?

FRANKLIN: This is about ’85, ’86. This was about six months out of high school. And it made me go to college. I went to Baruch College. I decided at the time I was going to study business. Still not sure about what the hell I was going to do.

JAY: It made you go to college. Why?

FRANKLIN: Because I felt like the alternative–the jobs that I was getting were really low-waged stock boy jobs lasting two or three months, not moving on anything, not doing anything for me. And it made me feel that there was something else that I needed to be doing. And the only way to get that was, even if I wasn’t sure what it is, it seemed like going back to school or going to college made sense. It didn’t make sense anymore.

JAY: Was there some of that is, if I keep on the path I’m going, I might be Tyrone?

FRANKLIN: I didn’t know. You know what? I can’t honestly say. It was more the shock of having somebody that you knew that was close to you that you’d made sort of a pact with that you lost for a senseless reason. So I wasn’t quite sure if I was the kind of guy who was going to be involved in some nefarious activity. I wasn’t that kind of guy. But I could have very easily wound up a guy who, through not caring, not being involved in anything, stayed where they were at. And that became scary for me also, just to be left where I was at, staying where I was at, not exploring anything, not–thinking I was pretty smart, but not using it for anything. And I really didn’t–at the time, could not figure out necessarily what I wanted to do or what I should be doing in my teens and early 20s, I guess. But it was during this time of going to college that more than the classes, finding a library was just sort of this place that became something special to me, right? And I think I took a black study course, almost haphazardly. And part of that was reading something on Malcolm X. And so I read the autobiography on Malcolm X, and it just was something that sparked inside of me of, like, an opening of, like, what the world was like. And so, when I compared, even though, obviously, it was drastically different circumstances in terms of the years, the conditions that he talked about in the ’30s and ’40s seemed very similar in some ways–some differences, of course, but very similar in terms of living in the projects or living in depressed communities. And when I looked around, like, the lack of resources, the lack of or bad education or opportunities, that stuff, reading the autobiography, rung true to me that it just didn’t happen, right? It just didn’t–all of a sudden, it’s through the bad luck of certain people, the nonwork habits of certain people that this kind of thing happens, that you don’t want to say, necessarily, a quote-unquote conspiracy, but these things were constructed and they became the places where people were sent or allowed to live in, and without resources, kind of what happens happens. Right? So I think that kind of opened up a real feeling of exploring or wanting to find out more about the world. And from reading the autobiography, I would want to read speeches by Malcolm or biographies of Malcolm. I probably could tell you what time Malcolm would go to the bathroom during certain parts of the day, I was so into it. And naively, I mean, I started reading Malcolm and I started reading other books and became really interested in social justice movement, interested in sort of black liberation politics. But my naivete at the time led me to go to a phone book and look for the phone number of the organization of Afro-American unity, which was the organization that Malcolm started before he was killed and was speaking about so long ago. Of course, I had to look in a phone book. There was no internet go on. But I was started–I think it was in my early 20s that I started really trying to figure out what it is that I could do in terms of sort of social justice and social movement, and really got committed, at least at the time, to the idea of being involved in social justice movements.

JAY: So not just about individual career, that your own, I guess, if you want, emancipation is dependent on some other people.

FRANKLIN: Yeah, that it’s dependent on some kind of community building, some kind of organizing, something political. And at the time, again–and I think I’ve probably done this most of my life–if I’ve less thought about a career, sometimes to my own detriment, and more about my interest in organizing and politics, which has led me to some interesting places and to do some interesting things, but it didn’t always put me on the best financial footing, right? So once I got consumed with wanting to organize, for me it became: what was the vehicle to do this. And I think in my early 20s I probably joined every young black organization there was Brooklyn, New York, probably five or six of them before I wound up finding a home in probably, like, 1995 through the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement.

JAY: So Malcolm was the inspiration for this movement of you. And in the next segment of the interview, we’re going to talk more about Kamau’s views of Malcolm X, how it changed him, and also some of the criticism he has or some of the recognition of what he thinks are some of the limits of Malcolm. So please join us for part two of Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

[simpay id=”15123″]

“Kamau Franklin is the founder of Community Movement Builders, Inc. Kamau has been a dedicated community organizer for over thirty years, beginning in New York City and now based in Atlanta. For 18 of those years, Kamau was a leading member of a national grassroots organization dedicated to the ideas of self-determination and the teachings of Malcolm X. He has spearheaded organizing work in various areas including youth organizing and development, police misconduct, and the development of sustainable urban communities. Kamau has coordinated and led community cop-watch programs, liberation/freedom schools for youth, electoral and policy campaigns, large-scale community gardens, organizing collectives and alternatives to incarceration programs. Kamau was an attorney for ten years in New York with his own practice in criminal, civil rights and transactional law.”