Shireen Al-Adeimi, Professor of Language and Literacy at Michigan State University, lays out the U.S., U.K., and Canada’s role in perpetuating the brutal Saudi-led blockade of Yemen. She exposes Biden’s continued military support of Saudi Arabia, despite the administration’s pledge to only send defensive support, and calls into question the misleading dichotomy of “offensive” vs. “defensive” military support. Is a peace deal more likely now that the Houthi and Saudi representatives have met in Sana’a?

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m Talia Baroncelli, and you’re watching theAnalysis.news. I’ll shortly be joined by Professor Shireen Al-Adeimi to speak about the war in Yemen and the role of the U.S., Saudi Arabia, and Canada in fueling this conflict. We’ll also speak about the history which led up to this conflict and potential ways to put pressure to ensure that it is brought to an end.

Shireen Al-Adeimi

The only reason Yemenis needed humanitarian aid was because they were blockaded and prevented from trading. It’s because their water facilities were being bombed. It’s because their hospitals were being bombed. It’s because, heck, even their schools, their homes, and cars were being bombed.

Talia Baroncelli

But first, please consider donating to the show by going to our website, theAnalysis.news, and hitting the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Most importantly, get on our mailing list. That way, you’ll be emailed every time a new episode drops. You can also go to our YouTube channel, theAnalysis-news, hit the subscribe button and hit the bell; that way, you’ll get notifications if you have your notifications enabled every time a new show is published. See you in a bit.

Joining me now to speak about the war in Yemen is Shireen Al-Adeimi. She’s a Professor of Language and Literacy at Michigan State University and is a non-resident Fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. So thank you so much for joining me, Shireen.

Shireen Al-Adeimi

Thanks for having me, Talia.

Talia Baroncelli

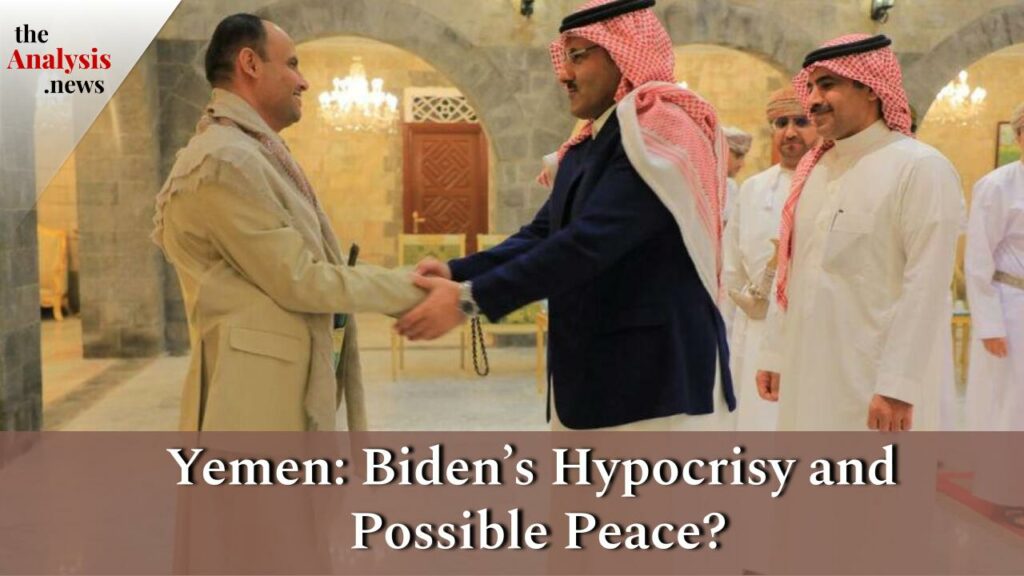

A few weeks ago, on April 9, we saw a positive image. We saw a handshake between the Houthi political leader, [Mahdi] al-Mashat and Saudi Ambassador to Yemen, Al-Jaber. Did you think we’ve reached a sort of breakthrough in this war right now?

Shireen Al-Adeimi

I think the peace talks have been very encouraging. Of course, we know that a ceasefire was reached back in April of 2022. For about a year, or more than a year now, there have not been Saudi-led airstrikes in Yemen, and that’s a positive development. That’s what we’ve been asking for, one of the things that we’ve been asking for so many years. It represents a change, at least in the war. The war is still ongoing, but it represents a significant change in the war.

I think the handshake and the meeting are certainly positive. I think it surprised a lot of people because it represents a Saudi recognition of the de facto rule of the Houthis. For the Saudi representative to go right into the heart of Houthi control, which is in Sana’a, and to meet with them, recognizes, I think, or shows that the Saudis finally understand who they’re dealing with. They’re not dealing with rebels, as they’ve been calling them for the last several years, even though, of course, the title still fits in many ways. They have organized themselves into a government over the last several years. They have been the de facto rulers. They control an area of Yemen where over 70% of the population, close to 80% of the population resides. I do think it’s positive. There’s still a long way to go before peace can be achieved. I think anytime people are talking to one another instead of dropping bombs, that certainly is a development that we should be looking at positively.

Talia Baroncelli

Do you think this potential peace deal would have legs if it doesn’t really incorporate some of the other political actors who have been involved in this conflict, actors besides the Saudis and the Houthis?

Shireen Al-Adeimi

I think for lasting peace, it absolutely has to include everybody. There is no getting rid of the Islah Party or members of the GPC Party, which is the party of President Hadi or former President Hadi, or the Southern Transitional Council, which is the separatist group, or the Houthis. There is no getting rid of any of these elements, no matter what people or how people feel about them. I do think that a lasting peace settlement needs to include all of these parties.

Now, the other thing we have to realize, too, is that the Houthis have been fighting all of these factions alongside those who are in the same camp as the Saudi-led coalition. So the STC is only powerful because they are backed by the United Arab Emirates. The Islah Party and President Hadi– President Hadi is not powerful, but members of his party and the Islah Party are only powerful because the Saudis have been funding them over the last several years. They’ve been based in Riyadh for the most part. I think we have to understand that when the Saudis are speaking to the Houthis directly, they’re not just representing themselves. In a way, they’re representing these other groups that they have been training, backing, funding, and hosting in their countries over the last several years.

Now, after a Houthi-Saudi settlement is reached, and if these foreign entities stop funding these groups and other groups, then I think there’s hope for Yemenis to actually sit around the table with one another and discuss a settlement and reach an agreement that works for all of them. As I said, nobody’s leaving the country. Nobody’s going to give up arms. Nobody’s going to give up their claims. Yemenis have to live with one another. They have to reach some agreement among themselves.

Talia Baroncelli

What do you think led to this particular moment right now where we’re seeing more dialogue, we’re seeing different leaders and representatives meeting in Sana’a? What led to this particular moment?

Shireen Al-Adeimi

So, if you remember, in early 2022, there were strikes in Sana’a that disabled Yemen’s internet for four days. No country has ever done this to another country and outright shut down its communication with the rest of the world. In that same week, there were attacks that killed 70 people at a detention center. There was this escalation of attacks, and it followed the UN not renewing this expert group which was supposed to hold the Saudi-led coalition accountable for some of what they were doing in Yemen. There were escalations on the part of the Saudi-led coalition, but at the same time, the Houthis escalated their strikes against both Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E.

For the very first time in the last several eight years, they were able to successfully, I would say, target some areas. There was an oil refinery in Jeddah that was hit. There was also a facility in the U.A.E. that was hit and it was not rebuffed by the U.A.E. or Saudi in time. So I think everybody had a reason to talk to one another. The Houthis were not able to rest Marib, which is a gas and oil-rich province, out of the hands of the Saudis and their coalition. At the same time, the Saudis were not able to move forward. There’s been a stalemate for several, several years, and now they saw that the Houthis were actually going to be able to cause some economic disruptions in their countries. I think everybody was incentivized to actually sit down and come up with an agreement that’s negotiated and mediated by Oman and come up with some kind of agreement that would work for all sides.

The Saudis, I think, have been exhausted by this. They have spent, by some accounts, $200 million a month on this war over the last several years. To spend that amount of money and not see your goals achieved in any way. They weren’t able to reinstate President Hadi’s power. Eventually, they ended up setting him aside. They weren’t able to recapture territories from the Houthis. What is it all for? I think there’s a recognition that, well, there’s all this pressure from U.S. Congress not wanting to support the Saudi-led coalition anymore. The Saudis are seeing that this was actually a war that they could not win. The Emiratis have a big question mark about their interests because they remain entangled in Yemen. I don’t think anybody’s really focused on their role or focused as much on their role. I think, at the very least, on the Saudi side, there’s an interest in extracting themselves from this war.

Talia Baroncelli

Yeah, the Emiratis are occupying an island just south of Yemen, and I know that they have played a role in this conflict. What has the role of China been given the recent rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which was in large part negotiated by China, but also by Oman? You also referenced Oman’s role in these negotiations. What is China’s role?

Shireen Al-Adeimi

I think it would be interesting to see what their role could be. China did not sell weapons to the Saudis or the U.A.E. They didn’t get involved in any way in the war. I think Oman is one of those other countries, and uniquely Oman, because every other Gulf country and many other Arab countries and African countries joined the Saudi-led coalition in one way, shape, or the other. Oman stayed neutral and has been hosting these talks for several years. This is not the first time they’ve hosted talks.

China worked with Iran and Saudi Arabia directly and reached some kind of agreement to reinstate diplomatic relations and whatnot. I think that’s a positive role. As for what they’ve done in Yemen, I would say, sure, any kind of peace talk or recognition of the resumption of relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia is a positive move and does relieve some of those tensions. Iran’s role in Yemen has been overstated over the last several years, so it doesn’t directly affect the peace talks that have been happening between the Saudis and the Yemenis themselves. Although, of course, it does help that a major ally of the Houthis, Iran, is now not in conflict with Saudi Arabia.

Talia Baroncelli

Do you think Iran’s, I would say, economic isolation, as well as the backlash against Iran, given the protests a few months ago, does this play into negotiations at all? Are the stakes higher for them to see peace in Yemen now, more so than before?

Shireen Al-Adeimi

I’m not sure what the Iranian intentions are. Again, I think that Iran’s role has been overstated in Yemen. When the war began, this was just a few months after the Iran deal was negotiated with the Obama administration. So for Iran to risk the Iran deal, I think, would have been foolish. There have been allegations by the U.S. that Iran has been involved. The Houthis have always said that they are not acting on behalf of Iran. There have been key moments where, for example, when the Houthis took over Sana’a in late 2014, the Iranians were very vocal about their stance against that takeover. The Houthis were like, well, who are you to tell us what to do? That was a pivotal moment. That is what set the spark that eventually led to this war in Yemen. So, of course, they’ve been supporting them in some ways, but not to the extent that they would be considered a proxy war or not to the extent that they were supporting, let’s say, the war in Syria. There are no Iranian Generals on the ground.

The country has been under blockade– air, land and sea blockade for the past several years. Journalists have to smuggle themselves in to report from inside Yemen. People are starving to death. There’s no medicine that’s allowed to enter the country that has been approved. Pharmaceutical companies have been trying to send medicine, for example. Aid has been rotting in ships because they’re not allowed to enter the ports of Yemen. Fuel that has been rerouted to Jeddah. Yet these allegations that Iranians are somehow getting through all of these blockades and supporting the Houthis have just been preposterous. They’re supporting them in other ways, just not in that way. Whatever support they’ve shown for the Houthis has been minimal compared to the ways in which the international community has supported the Saudi-led coalition. I think Iran wouldn’t want to risk it. I think it looks good for Iran to show that they are interested in peace in Yemen, even though the conflict itself has very little to do with Iran. It’s an internal conflict. It’s a conflict between Yemen and Saudi Arabia. It is a culmination of decades of intervention by Saudi Arabia in Yemen and decades of intervention by the United States in Yemen. This is not an Iran-Saudi conflict that’s happening at the borders of Yemen. This is a Yemeni-Saudi conflict that, unfortunately, is not even a war. It has been an asymmetrical attack on the country.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, before we speak about the humanitarian crisis in the country, you did touch on the history a bit. To give our viewers a bit more context, it would be good to speak about how this conflict came about. In 2011, there was an uprising in Yemen which ousted Ali Abdullah Saleh, if I got that correct. He was an authoritarian president, and he was forced to give power to his deputy, Hadi. So maybe you can explain what led to that and what people were protesting or uprising against, and how the Houthis came in to essentially take power from there.

Shireen Al-Adeimi

Yeah. Arab Spring, early 2011, Yemenis were watching what was happening in Tunisia and then Egypt. It seems like the protests were leading to positive change in these countries. I think for the first time, Yemenis, for the first time in a long time, not for the first time ever, because we have a history of uprisings and revolutions, but for the first time in a while, in, like, three decades, they found that maybe we could bring about change through these peaceful protests.

In January 2011, Yemenis started protesting. Now, they weren’t necessarily protesting Ali Abdullah Saleh himself, and only Ali Abdullah Saleh. They were protesting the entire system, which Saleh used to keep himself in power and to enrich himself at the expense of the Yemeni people. Yemen is the poorest country in the Middle East, has been for many, many years, and is now among the poorest in the world. Yet Saleh was, by UN estimates, one of the richest men in the world. Where is this man getting his resources from? Obviously, there was a lot of corruption. There was a lot of wealth that he, his party, and the Islah Party, which he essentially created as a controlled opposition in the early ’90s; this is like the Islamist Party in Yemen; they were all part of that system that people were uprising against.

Now, the movement was peaceful until members of the Islah Party saw this as an opportunity for them to co-opt the revolution from the people. Even though they were part of that system and they were long-time Saleh allies, they took the opposition. They went in opposition to Saleh himself and turned the conflict into a bloody mess. There was an assassination attempt. There was armed conflict. When he survived that assassination attempt, that’s when he agreed to transfer power to his Vice President, Hadi. Nobody wanted Hadi. They say he was elected if he ran in a one-man election, but that’s not an election; that’s an appointment. It was supposed to be a two-year term. It was extended by one more year. He resigned at some point and then unresigned. He was flailing around over the next few years, not knowing how to bring all of these different factions together.

Now, one of these factions was the Southern Secessionists, who didn’t even want to be part of the Union, and they didn’t want to be part of the Union since 1994 when there was a civil war between the North and South. They eventually reorganized themselves into the current STC, which is, as I said, funded and trained by the U.A.E. They had legitimate concerns that weren’t addressed.

The Houthis are a group from northern Yemen who initially started off in the late ’90s as a vocal opposition to Saleh’s corruption and Saleh’s rule, but also Saleh’s very close relationship to Saudi Arabia, which was becoming detrimental to Yemeni society. Here enters the sectarian conversation. This is not a sectarian war. The Houthis follow a version of Islam called Zaidi Islam, but they’re not a minority. Forty percent of Yemenis are Zaidi Muslims, and we don’t have a history of fighting along sectarian lines. What was happening in the late ’90s, early 2000s, and early ’90s as well is that Saudi Arabia was exporting their version of Islam, Salafi Islam and Wahhabi Islam, to all of these other countries like Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Yemen. I remember when the textbooks changed in school, and they came printed from Saudi Arabia. Now, what that was doing was an attempt to erase Yemen’s rich history of both Shafi’i-Sunni Islam and Zaidi-Shi’a Islam.

The Houthis were a family of scholars, and they had a representative in parliament. They were among the only people who were vocally outwardly speaking out against this, even though many people within Yemeni society did not like these changes that were happening. So that put them in opposition to Saleh, who, by the way, himself was a Zaidi, so this was not a sectarian issue. He didn’t handle critique very well, so he fought six different wars against the Houthis and was not able to get rid of them. In some of these wars, he enlisted the Saudis for help because he made the argument that these people are at your border, and they’re your problem as much as they’re mine.

So that’s the history with the Houthis. They became one of the groups, in post-2011, who were trying to have their voices heard. You know, they come from a province that was severely underdeveloped. We’re talking about no running water or electricity in many parts of the province. They had economic concerns as well. All of these different groups had their own concerns. Hadi was just not bringing together people in any meaningful way, and that’s what led to a lot of tensions leading to 2014, when the Houthis up and took over the capital, Sana’a, in an attempt to force Hadi into doing something about it.

I know I’ve spoken a lot, but I also want to highlight a key moment that happened between the Houthi takeover of Sana’a in late 2014 and the Saudi-led bombing in March 2015. During that time, there were still talks that were happening. The UN envoy to Yemen at the time, Jamal Benomar, writes about this in Newsweek. He writes about an agreement that was essentially reached between all of these different factions. He says it was ten painful weeks. He says the different parties agreed on the legislative and executive agreements. It was a power-sharing deal that was supposed to work for people. They were ready to sign the peace deal, and only two days later did Saudi Arabia start bombing. So that was the context. It wasn’t an all-out civil war. There was a lot of tension in the country. There was a Houthi takeover. There was a lot of resentment. There were a lot of parties who were left unheard, but they were still able to negotiate something. Now, we don’t know what would have happened with that, but they were able to negotiate a deal that was essentially derailed by Saudi Arabia intervening in 2015.

Talia Baroncelli

I have read about that. I was wondering, what was it that actually made Saudi Arabia intervene at that moment, what you say was two days after this potential peace deal had been negotiated? Did they already have U.S. support at that time, or did they think that they would be militarily supported and they were overly confident that they could push through their own agenda?

Shireen Al-Adeimi

I mean, they had U.S. support on day one. The day they announced their war, which was, by the way, in English from D.C., not in Arabic from Riyadh. They made the announcement that they were leading this war in Yemen called a ‘Decisive Storm,’ and that announcement was made in D.C. That very same day, the White House released a statement of support saying that they already created a Joint Planning Cell that they were supporting and that they were not at war because that was illegal. The Obama administration was very careful to say that they were not at war, but essentially everything they were doing signified that they were a party to the war and that they might as well have been part of that coalition because they were setting up Generals in the command room and supporting them with targets. Of course, most of the weapons that Saudi Arabia has comes from the U.S. So from the very, very first day of the war, they knew that they had full support from the United States, and the United States was very vocal about that.

Now, why did they intervene? They intervened in Yemen in the past. They intervened in the civil war in the ’70s. They intervened when northern Yemenis were trying to oust the imamites: the father, son, and grandson monarchy that was taking shape and turned Yemen into a republic. Saudi Arabia supported the monarch for the next eight years, even though he was a Zaidi, so religion here didn’t matter. They just needed another monarch or another ally. So when the monarchy failed in Yemen, and we turned into a republic, we’re the only republic in that part of the region and part of that world. All of our neighbors are monarchies. They made sure that they had an ally in Yemen, a very close ally in Saleh.

When Saleh was gone, they knew that Hadi was a very close ally. Now, they knew that the Islah Party would be allies as well. I don’t think they were too worried about the STC. The one group they certainly did not want in that agreement, in that power-sharing deal, was the Houthis because they had just spent the last several years fighting alongside Saleh to get rid of the Houthis and were really embarrassed by the fact that they weren’t able to control this group who has not backed away from speaking outwardly against Saudi interventions in Yemen or Saudi interference in Yemen. They didn’t want the Houthis in power, which is why they wanted to– what they said is intervene on behalf of the UN-recognized, legitimate president of Yemen, which years later, they had no problem setting aside, literally told him and woke him up in the middle of the night, said, hey, why don’t you resign and transfer power to these eight guys that we support? So that was the plan.

Now, the miscalculation happened when they thought this was going to be a quick two-week war, and they didn’t realize that when you attack people, they fight back. That’s the calculation that they did not make very well.

Talia Baroncelli

What was the extent of the support of the Houthis in 2014? What would you say characterizes their group? Allah is also the other name of the Houthis. What characterizes them? Do they have a specific long-term goal or political ideology that you think engenders broader support, or are they just filling in this sort of power vacuum, so to speak, and just fighting against the Saudi-led invasion, and that’s what’s perhaps giving them some more popularity?

Shireen Al-Adeimi

I think it’s a bit of both. When they took over the capital Sana’a, they were still some small group from northern Yemen. Yes, they had been gaining a lot of sympathy from their general population because, frankly, they were the only group that was able to stand up to Saleh and who seemed to not back down. I lived in the South when the South declared secession from the North, and Saleh responded by bombing us for the next three months until all of the leaders in the South fled, and the South was forced back into unity. Southerners and secessionists are looking at this, saying, oh, wow, we weren’t able to succeed. When we spoke about Saleh, your average Yemeni could not speak about Saleh without getting disappeared or being assassinated or something. This was a country that was under political repression.

The Houthis were seen as this group that raised armed conflict in response to Saleh’s attack on them because initially, they were speaking, and he attacked, and they fought back. They still weren’t anything significant. They weren’t a significant political party or anything like that. I think once they took over the capital in late 2014, people realized that they must have had support.

Now, who did that support come from? It turns out it came from Saleh, which is very ironic here. They had been enemies for many years, but Saleh, even though he resigned, he wasn’t your average Arab Spring president. He wasn’t assassinated. He wasn’t kicked out. He wasn’t jailed. He, in fact, remained in Yemen. He negotiated a deal under the GCC that would prevent him from being persecuted for any crimes that people were accusing him of and remained in control over large parts of the Yemeni army.

When the Houthis were able to very simply take over, march over from the North and take over with very little resistance, people felt like, well, Saleh’s telling the army not to act. That’s likely what happened because when the Saudis started bombing in 2015, very quickly, Saleh and the Houthis joined forces. He was able to mobilize parts of the Yemeni army that he still controlled, and they formed a unified resistance to the intervention. It didn’t last. It lasted for a good two and a half years. At the end of 2017, Saleh decided to switch sides. He saw that this was not going anywhere, and he thought maybe this was his second coming. He decided to switch sides, and within days, he was killed by the Houthis.

The Houthis then found themselves in Sana’a, now forced to rule. They did form a political group, an alliance with people from Saleh’s party. Initially, I don’t think they had any ambitions to govern, but that’s the role they found themselves in. Over the years, there has been no security situation in northern Yemen where they rule.

Now, if these were a very small group with no political power, every Yemeni would be armed to the teeth. You would see a lot of resistance against the Houthis. We don’t see a lot of that going on. In fact, we see the Houthis working with many northern tribes to gain their support and their trust. I think they’ve been able to do alliance-building work over the last several years and have been able to fold into their group many swaths of the Yemeni population who previously would not have been identifying with them at all. So they were seen as the people who stayed to defend the country, and that’s why I think a lot of people support them in northern Yemen. If the Saudis, U.A.E., and Americans were worried about the support that the Houthis had, well, now they really have something to worry about because now they have a lot of support from the population, whereas before, they didn’t.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, we can’t speak about this conflict without addressing the United States’ role in providing weapons to Saudi Arabia. If I recall correctly, the U.S. even sent in Green Berets at some stage in the conflict, and they’ve sent over $50 billion worth of military funds, weapons, and that sort of thing. Can you speak more about the role of the U.S. as well as the War Powers Resolution of 2019, which was vetoed by the Trump administration and which was recently rediscussed? I think Bernie Sanders was a bit reluctant and said that he wanted to speak to the Biden administration once more before putting it to a vote.

Shireen Al-Adeimi

Yeah, almost $60 billion have been sent from the U.S. alone to Saudi and the U.A.E. between fiscal years 2015 and 2021. So this doesn’t count (2022-2023). That adds up to about $22 million a day. We have that much in weapon sales just to those two countries. Then, of course, the Saudis and Emirates purchase weapons from Canada, Australia, Germany, Spain, Italy, Britain, and all of these countries. The other way that the U.S. supports the Saudi-led coalition and has throughout the years is through, as I said, the Joint Planning Cell. They actually have U.S. and U.K. commanders in the command room helping them with targeting. Up until late 2018, they were refuelling Saudi jets in midair. They weren’t only training their pilots and helping them with maintenance, spare parts and weapons, and helping them choose the targets, but these jets were flying midair over Yemeni airspace, and the U.S. was helping them refuel. That ended with the Trump administration in late 2018. So in every way, shape or form, logistics, intelligence sharing, choosing targets, weapons, every single way that a war operates, the U.S. had a hand in operating.

Now that essentially amounted to a violation of the Constitution. There’s a 1973 bill that was passed called the War Powers Act, and it became federal law in 1973 when journalists found out that the Nixon administration was secretly bombing Laos. They found out that and said, well, actually, we should not allow this to happen. We need to make sure that war-making is something that only Congress can authorize and not a president. Now, of course, we know every president has violated that since 1973: maybe not every president, but most presidents. Congress never really stood up to any sitting president until 2019. This was years of effort by activists in the making. Finally, in 2019, War Powers was passed in a bipartisan way, you could say by both chambers of Congress. It was largely seen by Democrats as Trump’s war in Yemen. There was no recognition of Obama’s role when we tried during the Obama years to end this war and hold the Obama administration accountable for what they were doing in Yemen. It was easier for Democrats, at least, to see this as Trump’s war, and they had the willingness to stand up against it. Trump vetoed it, and we didn’t have the two-thirds majority needed to undo the veto, so that fell apart. That was an effort to end U.S. participation in the war. It wasn’t going to end up in sales because, apparently, those are separate transactions. It was going to end all of these other logistical ways that the U.S. was supporting the Saudi-led coalition.

Now, Biden’s administration, here we go, 2021. In the very first policy speech that Biden gave, he made a promise to end what he called ‘offensive operations’ in Yemen. So this random dichotomy showed up in the vocabulary here, which it turns out that the Biden administration was not willing to define this for Congress, who was actively asking, hey, what does this mean? Not just that, but there’s a Government Accountability Report that came out last year that shows that the Biden administration didn’t have a definition for what is ‘offensive’ versus ‘defensive’. So it just said, we’re ending offensive participation in the war in Yemen, but continue to support the Saudis in the exact same ways that they’ve been supporting them throughout the last couple of administrations. We see here an unwillingness to break that alliance with Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia needs the U.S., and the U.S. needs Saudi Arabia. No matter what somebody says to get elected, these are the commitments that they have to answer for.

Biden did assign a special envoy to Yemen, [Tim] Lenderking. Honestly, when I spoke to him, I met with him when he was here in Michigan, meeting with Yemeni Americans. He sounded, and I told him this, I said, you sound like somebody who is a neutral party to the war. You can’t just go in and think that you’re going to make peace with Houthis who are refusing to meet with you and the Saudis when you have been a partner with the Saudis throughout these years. So the Biden administration, I think, is not willing to see itself that way. So we have a lot of work to do still.

It was really disheartening when, as you said, Bernie Sanders made another attempt at War Powers only to withdraw it because, frankly, the Biden administration threatened to veto it. He knew that it would be vetoed, and he felt like he needed more support. We saw an unwillingness by many Democrats to now stand up to a Democratic president again. Many of them were saying, well, we trust Biden. He said he was going to end it. Let’s just give him time. Meanwhile, the Saudi-led coalition was still getting a lot of support from the U.S. People start wars on a whim, and then it takes all of these years and sometimes decades to end them. Unfortunately, that’s what we’re seeing in Yemen.

Talia Baroncelli

The U.S. continues to supply weapons to Saudi Arabia, but it seems like they have also obstructed negotiations in the past. I don’t know if this was from the Pentagon leaks, but I think Tim Lenderking, who you mentioned, the U.S. envoy to Yemen, refused some of the Houthis’ demands, calling them maximalists when Houthis were calling for public employees, civil employees, government employees to get paid because their salaries hadn’t been paid out for years on end. He seemed to not think that this was worth negotiating and that it was a maximalist position. How can the U.S. even be considered to be an arbiter or neutral in this conflict when they’re still supplying weapons and actively obstructing some of the negotiations?

Shireen Al-Adeimi

Exactly. Let’s look at what he’s calling a maximalist demand. So, when the Central Bank was moved from Sana’a to Aden in 2016, they were using the Central Bank to pay government workers in the South, which, again, the South is 20% of the population and 80% of the population lives in the North. Those 80% of government workers were not getting paid. So all of these years, they were not getting paid. The Houthis, as one of the demands they made, is, again, this is not something that benefits the Houthis. This is something that benefits the average Yemeni. They were asking for this average Yemeni to get paid. They wanted to use oil and gas revenues to pay government workers. So we have oil and gas revenues that are being exported to other countries. This money is being pocketed by the coalition or their representatives in the South, certainly, not the average Yemeni because people are still starving to death. Eighty percent of the population is still in need of humanitarian aid. The Houthis eventually ended up in late last year when the Presidential Council essentially refused to use that money to pay for government workers, they ended up targeting those shipments. They said, well, you can’t export Yemen’s oil. That’s one of the very few times we’ve seen Houthi attacks in South Yemen since the war began. They basically gave up on the South in mid-2015, July 2015. In that instance, they said, well, if you’re not going to use that money to pay government workers, then we’re going to shut this operation down.

The Saudis were actually willing to say, okay, fine, let’s use those revenues to pay for government workers. Here we go with Lenderking saying these are maximalist demands. He kept repeating that term as though this was such a preposterous position. We see [Brett] McGurk showing up in Saudi Arabia and [Antony] Blinken talking to the Saudis, and the Pentagon leaks, of course. So you’re wondering, why is the U.S. trying to derail this? Frankly, it’s been big business for the United States, as I mentioned. The other thing is that they don’t want to seem like they’ve been sidelined. They were already sidelined by China when China negotiated this return to diplomacy between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Now they might be sidelined again by Oman, this time to actually negotiate a peace settlement in Yemen.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, you’ve spoken about how so many people have died in this conflict. There are different estimates, but approximately 375,000 people have been killed in the war in Yemen over the past eight years. Millions of people have been displaced internally, and some people have had to flee the country. The media coverage of the war has been few and far between. The coverage that we have seen, I feel, at least misses the mark and doesn’t really encapsulate the extent of the destruction and the gravity of this war. I’d be interested to hear your view on the lack of media coverage of this war.

Shireen Al-Adeimi

We have free press in the U.S. I have to remind myself that we have a free press in the U.S. I say that because many mainstream sources have not behaved that way in the context of Yemen. They have operated almost like government spokespeople to show a side of the conflict that the government approves of, to repeat Saudi lines and U.S. government lines very uncritically, without really looking at the root of the conflict. When they reported on this conflict, you often felt that this was some faraway thing, that, oh, it’s this proxy war, a civil war, or all of these terms that were just thrown around with no critical examination of them and no accountability for how the U.S. has been driving this war.

Literally, this war would not have continued for eight years. Maybe it would have lasted a couple of months without U.S. support, but certainly not to this extent and not for this long without U.S. support. Nobody asked Hillary Clinton when she was campaigning. Actually, one person asked Hillary Clinton when she was campaigning about the role of the U.S. in Yemen. She just looked at the reporter and walked away. She didn’t even respond. She didn’t even feel the need to respond to this reporter. There was no will to talk about Yemen.

Many of us Yemenis have wondered over the years, what is it about Yemen? Are we poor? Yes, certainly, we’re poor. We have no representative on a global stage who would stand up to what’s happening in Yemen. We don’t have all of these countries talking about, like, oh, poor Yemenis are being attacked by Saudi Arabia. In fact, everybody was lining up to make money out of these defense contracts with Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. because they knew that they had deep pockets. Unlike Ukrainians who were trying to flee the country and people were opening their doors to them, Yemenis found themselves shut in. That’s why you have four million people internally displaced and very little mention of any Yemeni refugee crisis because people were literally trapped. Countries that were previously giving visas to Yemenis were now no longer giving visas to them to even start off in those countries. Only the very rich and the very well-connected were really able to leave the country.

The U.S. supported the Saudi-led coalition instead of holding them accountable. It’s nauseating hearing what they talk about with Russia, not because it’s wrong, but because it has not been applied to the U.S. in the same way. Yes, Russia should not be attacking its neighbors. Yes, Saudi Arabia should not be attacking its neighbors. We shouldn’t be jumping to the defense of Saudi Arabia and helping them. Oh, you need weapons, you need logistics, you need training, or you need spare parts and maintenance? Sure, we’re here to help. That was the U.S. position. You would imagine that, especially post-Iraq war, when everybody was trying to be critical and self-reflective about how we let this happen, how did we let our government essentially lie to us about waging this war? You felt that maybe they wouldn’t do it again, and here we are. They did just that, and they let our government wage war. Now, it looks different. There are no boots on the ground except Green Berets, as we mentioned earlier. It was just a complete letdown. I think of Yemenis and their rights to life and their rights to freedom. A complete vilification of anything that was happening in Yemen. A mischaracterization of the war as either civil war, proxy war, and certainly shutting down any humanitarian avenue.

The only reason Yemenis needed humanitarian aid was because they were blockaded and prevented from trading. It’s because their water facilities were being bombed. It’s because their hospitals were being bombed. It’s because, heck, even their schools and their homes and cars were being bombed. It is not because there was some kind of drought and not because this was some kind of symmetrical war and they were inflicting similar harm to Saudi Arabia. We talk about Saudi and U.A.E. citizens who have been killed in this war, and maybe you can count them on one hand compared to the millions of Yemeni lives that this war has certainly affected through either starvation or the hundreds of thousands who have been killed.

Talia Baroncelli

It’s kind of ironic that so much humanitarian aid has gone to helping Yemeni people, and yet there is a Saudi-led blockade on the country, and that’s funded by the U.S., the U.K., France, and other countries. It’s almost like people are throwing money at the problem, but the political will is really not there to resolve this issue because so much money is there to be made.

Shireen Al-Adeimi

Humanitarian aid is a drop in the bucket compared to the need that this war has created. When somebody doesn’t know where their next meal is coming from, and that is millions of people in the country. Even with all of this humanitarian aid, we see a child dying every 75 seconds. Think about the gravity of the situation here. It wasn’t called the world’s worst humanitarian crisis for no reason. Yet you see the UN thanking Saudi Arabia and U.A.E. donors every time they needed to fill those pledges, or U.S. donors. Why? These are the people who have created this crisis to begin with. This is nothing compared to what they’re spending to destroy the country. They’re throwing crumbs at the Yemeni population as this charity, and getting thanked on a public stage, even though they’re the ones who have caused the Yemenis, by and large, to starve to death and to need this aid to begin with.

Talia Baroncelli

Yeah, they’re not making it possible for Yemenis to leave the country either. You could talk about Russia again and Ukraine and some of the double standards. I think, rightly so, Ukrainians have been accepted by neighboring European countries, but the destruction and the terrible conflict in Yemen should also necessitate a similar program, a coordinated program, which would also intake people who are internally displaced, but also refugees who are fleeing the country and fleeing this war, poverty, and devastation. At least in the European context, that hasn’t happened. I’m not quite sure about the U.S. context, but I would doubt that there is.

Shireen Al-Adeimi

No, it hasn’t happened anywhere. It hasn’t happened with Yemen’s neighbors. It hasn’t happened in all of these countries involved. Our airports were shut down, our ports were blockaded, and they were restricting movements within and outside the country. It just showed that human lives are not equal. You would hope that human lives are equal, but they’re not. We see the response to the humanitarian crisis and the war in Ukraine, and we’ve seen the response over the last several years to what’s happened in Yemen and, frankly, other countries as well, not just Yemenis. I think Yemen represents the most egregious because of how widespread this conflict is. Within months of the war, I remember reading a quote from the head of the ICRC at the time, I believe, and he said, Yemen in five months looks like Syria in five years. That’s how widespread the destruction was right away, right off the bat, in the first few months of the Obama administration getting involved in this. That’s how widespread it is. Humanitarians were telling us that this is how widespread the destruction is across the country. Yet the international community decided to let it happen, to try to throw money here and there at the crisis and not really think about why this is happening. We need to stop this immediately. We cannot stand for our government supporting this war and making so much money out of the misery of Yemenis.

Talia Baroncelli

One last question. You did speak about the press and how you were disappointed in the American press. I don’t want to generalize, but the majority of the mainstream press has essentially served as corporate shills for defense contractors, for the Biden administration, and Trump administration. They haven’t really held them to account and put pressure on them to end this war. Do you see certain potential positive changes coming about from the press shifting its role, or do you think civil society needs to put more pressure on the government for that to happen?

Shireen Al-Adeimi

Yeah, I don’t see the press all of a sudden changing. Some notable exception, I would say, is Nima Elbagir. She is a CNN reporter of Sudanese origin. She literally smuggled herself into northern Yemen and was the first in the mainstream press to talk about the blockade so openly because they didn’t want to call it a blockade. Lenderking denied the blockade even existed. Right now, we’re seeing [inaudible 00:46:38]. I mean, it feels like we’ve been gaslit for the last several years. Yemeni Americans and Yemenis said they feel like we’ve been gaslit.

Now, as part of the agreement with the Saudis and the Houthis, the Saudis have lifted the blockade off of South Yemen. What is there to lift if there is no blockade? They’ve apparently always acknowledged that there’s a blockade, but they’ve spent all of this time mincing words and saying, no, there are some restrictions, and we check for cargo and whatnot, and there’s an arms embargo, but it’s been a blockade since 2015. We see that in that report from [inaudible 00:47:17], this humanitarian crisis that was unfolding and the role of the United States in supporting this war. But that’s far and few between examples that we talk about in mainstream sources.

Now, non-mainstream forces have been all over this issue, and it’s been great and very critical. I do think civil society, we have to care about this war. Just because there are no boots on the ground, it doesn’t mean that the U.S. is not involved in a war. Why would Congress, in a bipartisan way, approve and vote for a measure that directs the president to end hostilities in Yemen if there are no hostilities in Yemen carried out by the United States? Like, that makes no sense. We have these lawmakers who all agreed that, yes, actually, the U.S. isn’t illegally involved in Yemen. We should stop them. Yet the average person here in the U.S. doesn’t really recognize Yemen as an ongoing war.

Now I see there’s even less of an incentive to do anything about it because there’s the sense, well, Yemenis, Houthis, and the Saudis are talking to one another, and so the war is going to end. Why should we bother with the War Powers Resolution? I do think we should bother with the War Powers Resolution because, frankly, it doesn’t matter what’s happening on the ground. It matters what we allow our sitting president to do or not do. The very least Congress can do is reinstate its authority over this thing that the Constitution allows them or gives them the authority to do.

Now, if the peace talks break down and Saudi Arabia begins bombing tomorrow, who knows? We need to send a strong message that whatever happens, the U.S. is not going to be supporting them in this war in this way anymore. I do think that pressure needs to remain here in civil society and also in countries where, sure, maybe the U.K. is a big partner in this war, but countries like Canada, for example, have benefited. The biggest arms deal was negotiated under the [Stephen] Harper government, but Trudeau’s government saw it through, and they’ve always made the case that, well, we can’t back from a deal. All of these legal scholars are saying, actually, you can back away from a deal that you know is involved in killing innocent humans, innocent people. We need to hold our own governments accountable for our own role.

Yemenis, they don’t want charity. They want accountability. We need reparations, and we need people to let Yemenis be and let them resolve their own issues. None of this would have happened if Yemenis were allowed to enact the peace deal that they were more than capable of making in 2015 and are more than capable of making in 2023.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, thanks for driving that message home. I think it’s really important for people to know what’s currently going on and how various powers such as the U.S., Canada, and Great Britain have been involved in this conflict and have pretended not to be involved, have had a very hands-off approach, or have actively derailed negotiations. This has been shown by some of the recent leaks. So I hope to have you on again, Shireen Al-Adeimi, to speak about Yemen. Hopefully, there’ll be some more positive developments in the very near future.

Shireen Al-Adeimi

I hope so, too. I hope we’re not talking about war anymore when we talk.

Talia Baroncelli

I hope so. Maybe we could speak about Yemenis culture or something more positive.

Shireen Al-Adeimi

Wouldn’t that be great?

Talia Baroncelli

That would be great. Well, thank you for watching theAnalysis.news. If you’re in a position to donate, please go to the website theAnalysis.news, and hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Get on the mailing list so you don’t miss any future episodes. Please also go to our YouTube channel, theAnalysis-news, and hit the bell and the subscribe button. See you next time.

[powerpress]

[simpay id=”15123″]

” Shireen Al-Adeimi is an assistant professor of education at Michigan State University. Since 2015, she has played an active role in raising awareness about the Saudi-led war in her country of birth, Yemen, and works to encourage political action to end U.S. support. She is a non-resident fellow at Quincy Institute.”

We have a ONE party system with kabuki on the outside! Any article you read highlighting HYPOCRISY is the one you need to pay attention to on both the left and the right. They are both ONE and the same interests. America’s system is a joke , the political system is not “straight”. It’s a joke.

whether one party is “racist” on the outside or not doesn’t even begin to describe how fake the whole system is.

A great informative discussion. Thank you.

As a Canadian I’m ashamed of successive government’s support here for the Saudi government. This country supplies armoured vehicles and, if I am correct, explosives to Saudi Arabia. Complete madness in my view.