The liberal elites don’t like real democracy and see mass movements as endangering their ‘educated and wise leadership’. Populism and anti-populism has deep roots in American history. Thomas Frank (‘What’s the Matter with Kansas’ and ‘The People, No.’), joins Paul Jay on theAnalysis.news podcast.

Transcript

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay, and welcome to theAnalysis.news podcast.

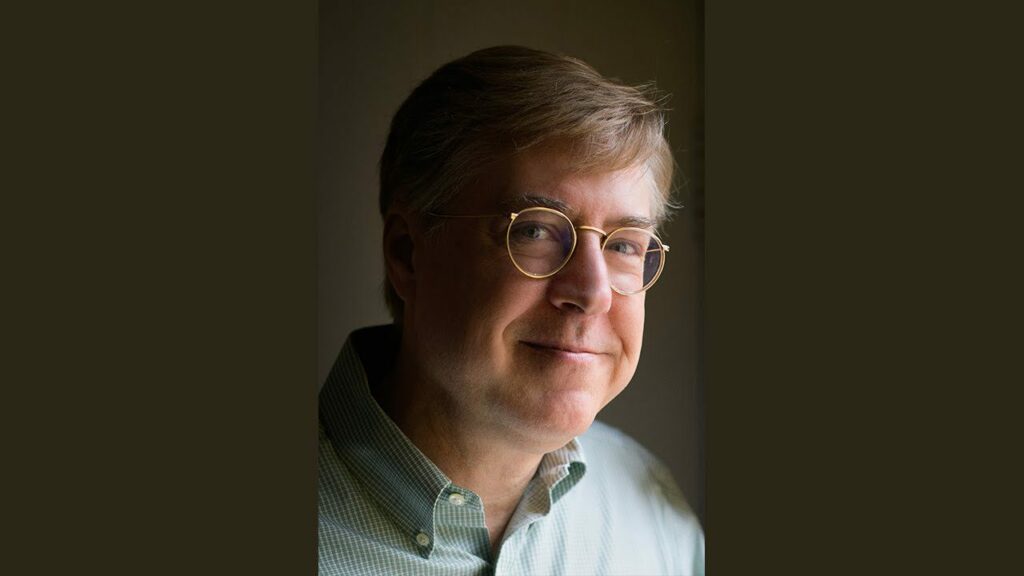

Born in Kansas, Thomas Frank, author of, ‘What’s the Matter with Kansas’, has with great insight revealed the disillusionment of large sections of working people in rural and urban America with the liberal elites that run the Democratic Party. In his recent book, he takes on the contempt that this liberal aristocracy feels towards what they call, populism. Here’s a quote from the book, ‘The People, No.’ “Opponents of the right should be claiming the high ground of populism, not ceding it to guys like Donald Trump. Indeed, this is so obvious to me that I’m flabbergasted. Anew every time I see the word abused in this way, how does it help reformers, I wonder, to deliberately devalue the coinage of the American reform tradition? It is my argument that reversing the meaning of populist tells us something important about the people who reversed it. Denunciations of populism, like the ones we hear so frequently nowadays, arise from a long tradition of pessimism about popular sovereignty and democratic participation, and is that pessimism, that tradition of quasi aristocratic scorn that has allowed the paranoid right to flower so abundantly”. That, again, is from the book, ‘The People, No’ by Thomas Frank. Thomas is a political analyst, a historian, a journalist. He co-founded and edited The Baffler magazine, and he’s written several books, most notably, ‘What’s the Matter with Kansas’ in 2004, and ‘Listen Liberal’, in 2016. I did a long series of interviews with Thomas about ‘Listen Liberal’, and I can attest to the fact that the liberals did not listen.

At any rate, his most recent book is, ‘The People, No’, and I guess that speaks to the same point. Now joining us is Thomas Frank. Thanks for joining us, Thomas.

Thomas Frank

You got it, Paul. It’s great to be here.

Paul Jay

So we’re going to divide this interview into three parts. Part one, we’re going to talk about the history of populism and especially in the American context. How did this word begin to be used to describe a political movement? Part two, we’re going to talk about getting into the heads of these liberal elites and the Trump version of populism, if that’s even how one wants to use the word. And then part three, we’re going to talk about what would a democratic populist movement look like if one imagines what it should be and what it is today. But let’s start with the history, but before we do, let’s talk just a little bit about the title of the book.

What was your thinking behind ‘The People, No’?

Thomas Frank

So it’s a reference to an American classic that’s not widely read anymore. It’s a book-length poem by Carl Sandburg called, ‘The People Yes’, and Sandburg was you know, they called him, in his heyday of the 1920s and 1930s, they called him the poet of the people. And his whole career was about making poetry out of the language and the experiences of ordinary people.

There’s something of a tradition of this in America. So Walt Whitman did the same kind of thing, and there are many others who have done it as well. But Sandberg was in some ways the best known and most popular poet who sort of worked in this particular vein. And he wrote this book in 1936, ‘The People Yes’, it was a populist book in a populist era. I mean, the 1930s were the great period of celebrating ordinary people, you know, folk traditions, painting WPA murals of average working people. And also at the same time, the labor movement was growing and taking power and the American government was shifting dramatically to the left. And none of those things are the case anymore, Mr. Jay.

I mean, the elites in this country are fearful of democracy. We just came out where, you know, just a few years ago we had an election which the Democratic candidate, in other words, the legatee of Franklin Roosevelt referred to ordinary people as ‘deplorables’. And one of the most shocking statements of the campaign, actually that was Hillary, of course, Hillary Clinton, she apologized for it, but the damage was done. That is the mindset of leading liberals nowadays is that there is something wrong with ordinary people. I mean, they say this, by the way, you know, your listeners might think that this is just so much rhetoric, they say this, the first chapter of the book is made up of quotations of these kinds of elite liberals in Washington, D.C. denouncing, and wringing their hands over ordinary people and how they have abandoned the elites. You know, the people are in the grip, they think of some grand delusion.

Paul Jay

Often when they attacked Bernie Sanders, meaning the Clintonesque, and Obamanesque, one should add, a section of the leadership of the Democratic Party. They often equated Sanders with a kind of Trump, denouncing him two forms of populism. That’s because it’s outside the institutional control of them.

Thomas Frank

Yeah. Of them and their Beltway doppelgangers in the Republican Party. Yes, that is exactly right. So in my definition, which begins, you know, where it should begin with, the people who coined the term, Bernie Sanders is very much in the populist tradition, and I’m sure we’ll talk about him and what happened to him at some point. But Donald Trump is not, Donald Trump is something else. Donald Trump is a classic demagogue, which is another interesting sort of thread in American life, the problem of the demagogue. But it’s not the same thing as populism.

Paul Jay

Well, they, as you point out in your book, in their minds, because populism just means a politics out of the normal control of institutional two-party politics and causing normal two-party politics. I’m not sure the current Republican Party itself falls into that, but they see anything like that, it’s just mob rule.

Thomas Frank

Yeah.

Paul Jay

And it’s out of control, it’s scary, and these people are defying the normal historical process.

Thomas Frank

Yes. Now, just so your listeners know, this is not just one or two people here. There’s an entire academic discipline now, or it’s sort of a quasi discipline, you know how academia is. There are these sorts of places in between departments, but it’s called global populism studies. And that is their definition of populism is more or less it’s mob rule. It’s when the people are out of control and they start following these racist demagogues would be authoritarians who want to overthrow rule by rightful elites and by rightful elites. Of course, I mean people like themselves, them and their friends.

Paul Jay

Yeah, you have a good line in the book. Populism is simply another word for mob rule, a headlong collapse into the tyranny of the majority that our founding fathers so dreaded.

Thomas Frank

Yeah.

Paul Jay

And that’s the whole point of Electoral College, which is, as you say, rather ironic that people that don’t like populism wound up losing to an institution that was there to fight populism.

Thomas Frank

I know, so everything is riddled with contradictions and ironies, in the Electoral College. The founding fathers obviously didn’t have the word populism, but they did have that fear of the majority. That is all that runs right through the Federalist Papers and the Constitutional Convention. Alexander Hamilton, famously, well, it’s actually not clear whether he said it or not, it’s one of these apocryphal quotes, said things like it all the time. But the quote itself, he denied saying it.

And that is, at one point was in an argument with his arch-enemy, Thomas Jefferson. He said, ‘your people, sir, are a great beast’, and that’s anti populism. That’s kind of the core doctrine of it, that the people are this uncontrollable wild animal. And by the way, there’s these great illustrations of that idea in, well, I say they’re great because I’m the one that found them and put them in the book. But if you go to my website, if you go to tcfrank.com, you can look at a lot of them, of these illustrations of the people as a great beast and with the word populism inscribed on the people and this is from the 1890s, and it’s the same idea today, of course.

Paul Jay

I’ve made this point in discussing modern slavery that in the context of America and the slave enslavement of black slaves, black African slaves, but that in England, the enslavement was of the Irish and the Welsh and of child labor, which essentially was like child slaves who were white Anglos. The idea of dehumanization, the working class, especially the poor working class, as really being subhuman, it’s connected to this idea that if those people ever got in charge of or supported the kind of politics that serve them, that’s to be feared.

Thomas Frank

Yes, and that is one of the themes that runs right through the history of populism, is or I should say, of what I call anti-populism, is this fear that if you were to actually succeed with what the populists wanted to do, which is to make a grand appeal to working people on class interest rather than on, you know, racial interest or something like that, race discrimination or white supremacy or something like that if they were to ever do that and succeed with that, there would be hell to pay. And they have succeeded in American history there have been instances where that sort of thing appealed and all my life I’ve been waiting for it to work again.

Paul Jay

Talk about the history in the United States. So where there actually was a movement that self-identified as a populous party. So what is the history?

Thomas Frank

Yes, and so this is one of the funnier things, Paul, with launching this book is, you know, I got there and put it on Twitter and on Facebook, and there’s all of these people who are like, you know, everybody says they’ve got this model for populism, but nobody knows anymore that there was an original–there were people who made up the word, consciously invented the word, and there was an original populist movement. For me, this is a very familiar history because I’m from Kansas. I’m sitting in Kansas right now as I’m speaking to you, and I’m about 20 miles from this spot where the word was coined, okay. And it begins in the year 1890, well, begins before that. There was a group called the Farmers Alliance that started organizing, far back then, the majority of the U.S. population were farmers. Kansas is a farm state, and the farmers were in deep trouble, deep economic trouble, and there’s a group called the Farmers Alliance started bringing them together and organizing them to figuring out ways to do something about their terrible predicament. This group was enormous. One of the biggest mass movements of all time in American history.

And they didn’t succeed using the various political methods at hand, and so they went into politics themselves and they started a third party, and it was the last of the great third party efforts and also the most successful of them. And they were able to take power in the state of Kansas and in a bunch of other places as well. Overnight became it this sort of prairie fire, this huge movement. This is in the year 1890. And when my story begins, it’s 1891, the Kansas populists have just gone to a convention in Cincinnati where they have launched their movement on the national level. And they’re on their way back to Topeka, and somewhere between Kansas City and Topeka on the train, they were sitting around with a local Democrat and trying to invent a name for a word to describe people who are members of the People’s Party, that’s what they call themselves, the People’s Party. And they came up with the word populist and they appeared in a newspaper a few days after that and caught fire. The word caught on and the movement caught on, and the movement grew by leaps and bounds over the next few years. And they ran a guy for president in 1892 didn’t succeed, but they won a lot of other offices. They had a delegate, you know they had a bunch of them in Congress, a bunch of U.S. senators, a lot of governors, mayors, et cetera. And you want me to just keep going with the story?

Paul Jay

Yeah, go ahead. The only question I’d ask at this point is in the United States to some extent and certainly many other parts of the world, a kind of conscious socialist movement was also developing around this time.

Thomas Frank

Yes.

Paul Jay

How influenced was this populous movement with socialist ideas?

Thomas Frank

Very! If you want to put aside whatever doctrinal differences they might have had with other Left-Wing parties at the time, the populist party in America was basically the equivalent of the Labor Party in England or in Australia and there were other Left-Wing parties cropping up around the world. One of the things that historians often talk about is why there is no socialist or Democratic Socialist Party in America. The reason is that we did have one, it was populism and it failed. And we’ll get to that part of the story, it failed or was suppressed, depending on how you look at it. But there was an effort to start one, and it was these guys in Kansas and their grand idea, they wrote a manifesto in 1892, it’s really something, it’s well worth looking up on the Internet and reading, their grand idea was to build a huge a union of all the working-class reform groups. So unions, together with farmer groups, et cetera, and build a gigantic coalition of the working class to challenge the well, the capitalist system.

That was the idea, and for a while in America, it looked like it might succeed. Farmers had been having a hard time for 20 years for all sorts of different reasons, because of railroad monopolies, because the currency was contracting, all sorts of other reasons. And then the country went into a terrible economic depression. And in 1894 in America, you had one of the first big nationwide strikes, a railroad strike that was called the Pullman strike, led by Eugene Debs. You had a march on Washington of unemployed people it’s the first time that had ever happened, it was organized by a populist. And it looked like the populist party was perfectly situated to take advantage of the depression that the country was going into.

Paul Jay

How large was that march on Washington?

Thomas Frank

I don’t remember how many people participated. Maybe 10000, probably less. It wasn’t in terms of numbers, it wasn’t like the one in 1963 or the one in the 1930s, but it shocked people. It was incredibly shocking. They called it Cox’s Army and it was headline news all over the United States and was regarded as deeply shocking, and they threw the leader of it in jail once he got to Washington for walking on the grass.

You know, this is the the the people in charge in America at the time, you got to remember where you know, it would not be right to call them extreme right-wingers because, by the standards of their day, they were it, they were the center, they were the left, they were the right, they were the only thing, the only game in town. But by our standards today, they were extremely conservative.

You know, they believed in government having no role in the economy except to prop up banks, to get banks out of trouble, never helping out unemployed people, the government should intervene to put down strikes, should intervene to stop any kind of protest movement that rises up, these elite that I’m describing who ruled America were incredibly racist. And that’s just how they thought about the world. They thought there should be no taxation of incomes or fortunes, no regulation of railroads or monopolies, that’s just how they viewed the world.

Paul Jay

It’s kind of ironic because so many of the working people now in Kansas and other parts of rural and suburban America who are supporters of Trump for the Republican Party, you know, they have this idea of the good old days. I think the good old days, their equals we’re part of this progressive, populist, socialistic movement. That’s what the good old days were.

Thomas Frank

Well, Paul, yes, you’re right. One of the, you know, like recurring features of American life that makes everything possible, that makes the whole thing tick, is that we don’t remember the past.

Paul Jay

Well, you know Gore Vidal’s line on that, right? You know, the USA, the United States, he changed it to amnesia and from amnesia, he changed it to Alzheimer’s.

Thomas Frank

Studs Terkel once said that to me, in different words, but that’s what he thought was our great problem, we couldn’t remember anything.

Paul Jay

Well, you can thank the education system for that.

Thomas Frank

Yes, but you can also thank the powers that be. I mean, you think you look at the most highly educated people in America running The New York Times and they use the word populist in this negative sense all the time, they have no recollection of it. They hated it then, they hate it today. Anywho, the story comes to an incredible climax here in just a second, which is this. So the country is in turmoil, populism looks like it’s the wave of the future, it’s the coming political party, and then as often happens in American life, one of the two major parties decides to capture this reform sentiment, this protest sentiment that’s out there in the country, and in this case, it’s the Democratic Party.

And the Democrats meet for their convention in 1896 and they toss the incumbent president, Grover Cleveland, overboard. They’re not going to renominate him, he’s out. They turn against the gold standard, the gold standard is the great sort of religious faith that props up American capitalism at the time. And the Democratic Party says if we get in, we’re taking the country off of gold. And then they nominate for their presidential candidate, a 36 year old from Nebraska named William Jennings Bryan, who’s completely unknown, never heard of and who has just given this incredible speech attacking the gold standard. And they choose this guy for their presidential nominee. And then a few weeks later, the populist party, which has made its convention, says, OK, Brian’s not perfect, we have all these other issues, too, everything from women’s suffrage to nationalizing the railroads, to the eight hour day, you know, all these other issues, and he’s not on those. But we’ll get on board with him because he looks pretty good and it’s probably the best we can hope for. And so they endorsed him also. And when these two things happened, the elite of the United States went crazy. They went into a kind of hysteria and I call it a democracy scare. The leading newspapers of the country, combined with the leading academics of the country, the millionaires, the captains of industry, all of them, joined hands and went hysterical together, hysterical that this was happening to them. That one of the two major parties had been, as they saw it, captured by radicalism and they proceeded to denounce William Jennings Bryan in the most outrageous, shocking terms. And I have a really, in my mind, kind of amusing collection of this. It makes up a whole chapter of the book, I call it, ‘the democracy scare of 1896’, their war on William Jennings Bryan, which is really quite incredible, this airtight consensus among the American elite that this man had to be stopped. He could not become president. And they rolled out every rhetorical device against this guy, every kind of Election Day corruption that was sort of available to the 19th-century mind was used against him, and they defeated him. By the way, they raised, the Republican Party raised, and spent an extraordinary amount of money, by some standards, bigger than has ever been spent. To this day, you got to remember, it was unregulated back then, there is no regulation. The Republican candidate was a guy named William McKinley, a senator from Ohio, and his campaign manager was a tycoon from Cleveland called Mark Hanna.

Mark Hanna is legendary. Karl Rove imagines himself as a kind of, you know, in Mark Hanna. Karl Rove has written a biography of a book about this moment, this election.

Paul Jay

JP Morgan must be at the center of most of this.

Thomas Frank

Hannah was the organizer. I don’t remember if Morgan-

Paul Jay

He’s telling, he’s dictating to a large extent his real rights and others, he’s creating these monopolies.

Thomas Frank

I think Morgan was immediately after this election was his heyday or it might have been right before, but his heyday was right after this. But there were, the other tycoons. Vanderbilt was in full effect, of course, you know the other tycoons, Rockefeller, of course, Standard Oil was up and running, Carnegie was probably the richest man in the world at the time. You know, U.S. Steel called Carnegie Steel at the time. But, you know, all of these guys, of course, hated, feared, loathed populism.

And Mark Hannah would go, at one point in the campaign, went door to door to the headquarters of the great American corporations in Manhattan and said, it’s incredible that this happened, he said to them, “Open the books”, and they did. And he said, “Here’s what your profits were last year, we the Republican Party, the Republican campaign is taking, you know, whatever percent of those profits. That’s what you’re giving to this campaign. It is part of the class war to stop William Jennings Bryan”.

And they paid they anted, and here’s the kicker of it, the word that they use to describe Brianism, the fear that the danger of Brianism, the one word that they settled upon was populism. It said this is populism, it’s mob rule, it’s the danger of the mob. That they’re going to come in and overthrow the legitimate government. They don’t know what they’re doing, they’re crazy, they are mentally ill. The whole sort of stereotype that we see nowadays, they want to destroy norms the way this country has always been run. But above all, what their idea of populism was, is that it represented people who had no business ruling, who had no business making laws.

Paul Jay

They must have been particularly concerned, you write in the book in the 1880s that the Farmers Alliance, which was sort of the underpinning of this Proteau populist. Yeah, that there was also a Colored Farmers Alliance that was in alliance with White Farmers Alliance. That must have really scared the elites.

Thomas Frank

In the South it did. Yes. So that’s a sort of a related story, but slightly different. So populism had, its stronghold was the Plains states, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, the Dakotas, where it pretty much-swept everything before it. But they also were very strong in the South and the South, obviously a very poor part of America at the time, obviously, everyone, the vast majority of the population there are farmers, largely tenant farmers. And populism is their proposal to the farmers of the South. The South, by the way, was a one-party system, the one-party being the Democratic Party, which was the architect of white supremacy. And the way the Democratic Party held power in the South in those days was by appealing to whites, saying that your interests, your racial interest is greater than your class interests, your racial interest, and they did this in a thousand disgusting, loathsome, racist ways.

And it’s kind of hard to write a history about this period because it involves reading really vile stuff. But this was what they called the bourbon Democrats, the people who ran the South, the ruling elite of the South, and populism rose up against these people. And the proposal that populism made to the farmers of the South was that ‘No, your class interest is greater than your racial interest’. And so populism very famously made an appeal to black farmers as well as white farmers to come together in their common class interests and to do something to improve their position in life. And this was not idle. This actually had a chance of succeeding. And, yes, that was absolutely terrifying to the masters of the South, absolutely terrifying. And you mentioned, what’s now referred to as, the Black populists, and they were not insignificant. They made up a big part of the populist vote in southern states. At the time, African-Americans could still vote in a lot of the southern states, and so the populous said, we’re going to go out there and compete for their votes and we’re going to do this obvious thing, which is we’re going to give them a better deal than the Democrats are.

Oh, my God! This story is famous, because of how the bourbon Democrats reacted, which is to roll out every imaginable kind of racist device to scare the whites back into line, and when that failed to use every kind of Election Day skullduggery to count them out, to make sure that populace did not get elected, they did prevail in one southern state, that’s North Carolina. The story there just is so incredibly awful, how the Democrats finally got them back, but they did

Paul Jay

So in 1896, you’ve got this Democratic Party convention, they dumped President Grover Cleveland, they nominate William Jennings Bryan and the elites go nuts. So what happens?

Thomas Frank

They pull out every stop and they outspend Bryan in the most, we don’t really know because they didn’t have to report, there are no reporting requirements or anything, probably 20 or 30 to one. Bryan had, virtually, no campaign funding at all because obviously, he’s promising to take the country off the gold standard, which would have ruined, you know, the banking community and small town every with everyone down to small town merchants, you know, would have been in trouble. So they come together as a class to stop him. He’s going around the country, he’s kind of a novelty because he’s won the nomination of the Democratic Party on the strength of his oratorical ability, and so huge crowds come out to see him.

Paul Jay

So why did this getting off the gold standard appeal to the populous?

Thomas Frank

Good question. So this is one of these forgotten little chapters of American history. The gold standard is what’s called ‘deflationary’ because the supply of gold doesn’t grow very much every year, but at the time, in 1890, the population was growing by leaps and bounds, the economy was growing by leaps and bounds, but the currency was not. And so what that means is that it’s deflationary, so the value of the dollar goes up and up and up every year, its the opposite of inflation. If you are a banker or a bondholder or a capitalist, this is wonderful for you. If you are someone who borrows money, which farmers did at the time and still do today, farmers, they’re always in debt, right, they have to borrow to make ends meet. This is crushing. You have to pay off your debts in dollars that are worth far more than they were when you borrowed them.

So the price of, say, corn goes down and down and down and down, but your debts, the burden goes up and up and up. And so you have farmers in the West and farmers in the South are basically approaching a state of debt peonage. In the South, that’s where they are, that is what has happened. So yeah, getting the country off the gold standard was, a huge part of the problem, and we eventually did do that. You know, we don’t have the gold standard anymore. The same is true in Canada.

But the public embraced this issue in a way that is difficult to understand nowadays and said now what we should have is a silver standard because silver is inflationary. There’s a lot of it. You know, it comes out of the ground every year. And so it became what they called ‘The Battle of the Standards’, where Bryan supported silver and McKinley supported gold.

Paul Jay

And voters actually understood the implications of this?

Thomas Frank

Yes, oh, absolutely. Well, they did very much so. And they also embraced it in a symbolic way. So gold was symbolized by great wealth, gold was supposed to be the currency of the rich, and silver was supposed to be the currency of average people. Yes, they definitely understood this.

Now, for a time in the beginning after the convention, Bryan seems to be this man of destiny. And everybody thought he was going to win, it seemed obvious, look what’s coming, it’s his tidal wave. But the Republicans were with the campaign that I describe in the book. And the sort of hysteria among the ruling elite of this country. We’re able to beat him back, I mean, they used every kind of crooked method that you can imagine. But they did it, they beat Bryan and staved off the challenge of populism.

Paul Jay

And the movement kind of fizzled after that. But you write in the book that even if the movement fizzled, many of their demands actually came true and not that much longer. Go about what kind of changes arose out?

Thomas Frank

Oh, well, so like if you look at the what the populists wanted to do, almost everything on their list later became law via other politicians and other parties. So, for example, the direct election of senators, they wanted to do that, that happened. The secret ballot, you wouldn’t think that’s a kind of an obvious reform, that happened. We have that everywhere now. The initiative and referendum, we have that. Votes for women, that happened. Populism was the first party to endorse that. On their economic issues, we did start breaking up monopolies, took a couple of years, but we started doing it. We regulated other monopolies like the railroads. We are very strictly regulated in this country. We did go off the gold standard, it didn’t happen until 1933, but we did do it. Right down the list, almost everything they wanted to do eventually happened

Paul Jay

You’re right that rich people got the income tax, that wasn’t true before there.

Thomas Frank

The first income tax was passed by populists in U.S. Congress, working with Progressive’s from the other two parties right before that election, I think 1895, it got struck down immediately by the Supreme Court, very famous Supreme Court decision. They said that the income tax was an act of class war, right. This was the worst elements of society, voting a tax on their betters.

Paul Jay

You’re from Kansas and because of the book, you’ve made an extra effort to get to know and talk to people of Kansas, do people understand that the current right-wing politics that so dominates in Kansas and places like there. That the history of their own families there is so different than so much of what they condemn these ideas began through their ancestors that.

Thomas Frank

So, Paul, I don’t know what to say. No, we don’t know that that knowledge is lost. There are no monuments to populism except for private ones. If you go on eBay, it’s incredibly hard to find any kind of ephemera associate, they didn’t have any money. I mean, these were very poor people. There’s nothing, nut as you saw in the book, I was able to hunt down all kinds of hilarious ephemera from the campaign against populism. That’s very easy to find, you could buy it on eBay, that sort of thing. But, no, there’s no collective consciousness of that. And, you know, this is one of the problems in American life is that the way that we remember the past is so distorted now, we should probably come back to this in episode two or three, the way the word populism got distorted by historians who deliberately decided to twist the word for their own reasons.

Paul Jay

And I think the other thing in terms of when this movement started to fizzle out, it’s really the beginning of the 20th century is the real rise of finance and the real beginning of financialization. And by the 20s, everybody’s being sucked into buying into the stock market and borrowing money to buy stocks, and this whole frenzy of speculation and everyone was going to be a wealthy capitalist.

Thomas Frank

Yeah, the eternal dream. Well, there’s a famous article, on The Time. What is it? Oh, my God. ‘Anyone can be a millionaire’ or ‘everyone could be a millionaire’. I’m sorry. I wrote a book about this long ago called One Market under God about this kind of the pseudo-populist promise of that kind of capitalism, and every time it just continuously suck all these people in and then pull the rug out from under you. But when they did that in the 20s, it led to a great moment in American life, which is the rise of the New Deal and the labor movement and real reform.

Paul Jay

OK, that’s gonna be part two. So we’re going to end this part of the interview. And part two we’ll keep going historically for now and deal with what populism looks like in the 1930s and the New Deal. And, you know, if you read some of the speeches of Roosevelt, particularly this very critical year of 1936, Roosevelt sounds more radical, frankly, than anything you even heard from the populist movement.

Thomas Frank

Oh, yes.

Paul Jay

All right, so join us for part two with Thomas Frank on theAnalysis.news podcast.