This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced on August 22, 2014. Mr. Horne says the Civil War liberated enslaved Africans but then led directly into the construction of the Jim Crow apartheid regime.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself.

Now joining us again in the studio is Gerald Horne. He’s the author of The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America and about 30 other books.

Thanks for joining us again.

GERALD HORNE, HISTORIAN AND AUTHOR: Thank you.

JAY: So we’re going to jump ahead now. You’ve said you’re going to come back and we’ll be able to do more of this history in more detail. But let’s kind of make the leap to the Civil War.

As you’ve argued earlier, much of the construction of capitalism in the United States is based on these massive profits that were developed in the slave trade. The Revolution of 1776 you call a “counter-revolution”, in the sense that it was to maintain the institution of slavery. But that starts to change as capitalism develops, particularly in the Northeast. Why can’t industrial capitalism in the Northeast accommodate slave society in the South? Why couldn’t they get along?

HORNE: It’s a good question that requires a complicated answer. One is that after the Haitian Revolution, 1791-1804, it gives a jolt of adrenaline to the movement to abolish slavery. It helps to encourage London in particular to start moving away hesitantly and reluctantly from slavery, not least because of Haiti’s proximity to their cash cow that is Jamaica. Like revolutions before and since, the Haitian revolutionaries were interested in spreading their gospel throughout the hemisphere, not least in neighboring Jamaica. So once again Britain is faced with the prospect of either a helter-skelter retreat from slavery towards abolition or a measured retreat, which of course takes place 1833-1834 with abolition throughout the empire.

Secondly, U.S. leaders used to argue that Britain in a sense was jealous of the United States because the U.S. leaders thought that the U.S. was beginning to exceed Britain because it was more adept at the slave trade. It had a larger landmass. For example, after Britain lost the 13 colonies, it lost a major market for enslaved Africans. The U.S. nationals could then build upon that market to then expand into Cuba, expand into Brazil, etc. And from their point of view, Britain was moving away from slavery not because of morality and the campaign’s of William Wilberforce and all of the rest, but because it was just being squeezed out of a market, and therefore it then ascended to high ground of moralism and equipped the Royal Navy to stop U.S. ships on the open seas, which leads to further conflict with Washington, with the United States, over the question of slavery. And in a previous book I made the argument that it’s British abolition and the strength of British abolition for whatever reason, whatever motivated by economics or moralism or a combination of the two, that puts enormous pressure on the United States to move away from slavery because the abolitionist movement, the movement to abolish slavery in the United States, was heavily dependent, both politically and financially, and from the point of view of obtaining simple arguments, they were dependent on their counterparts in London.

And then there’s the question of whether or not slavery was becoming a fetter on the productive forces of the United States of America. As you’ve already noted, even though slavery was profitable, questions were beginning to arise whether or not the United States could become even more profitable without slavery, not least because slaves oftentimes tended to destroy the instruments that they were working with. And keep in mind that slaves were not just deployed in the fields in Virginia; they were deployed in factories, there were deployed in mines, etc. But if they’re destroying the enterprise that they’re working in, questions are raised about profitability.

And then there’s the idea that under slavery, that you’re shrinking a market. That’s to say, if you have wage workers and you pay them money, then you can get it back by forcing them onto the market to buy food, to get housing, etc.

JAY: You also can’t fire a slave. I mean, it’s a big–if a slave doesn’t work very hard in your factory, what are you going to do except terrorize the person?

HORNE: You terrorize the person and you sell them down the river, you know, you sell them to Cuba. But in any case, that’s not–oftentimes that’s not very practical.

So there are many forces that are pushing the United States towards abolition, but not necessarily pushing the United States towards antiracism. I think that’s oftentimes confused. That is to say, the U.S. Civil War is oftentimes seen as not only a war against slavery, and even that’s questionable.

JAY: But it wasn’t a war against whiteness.

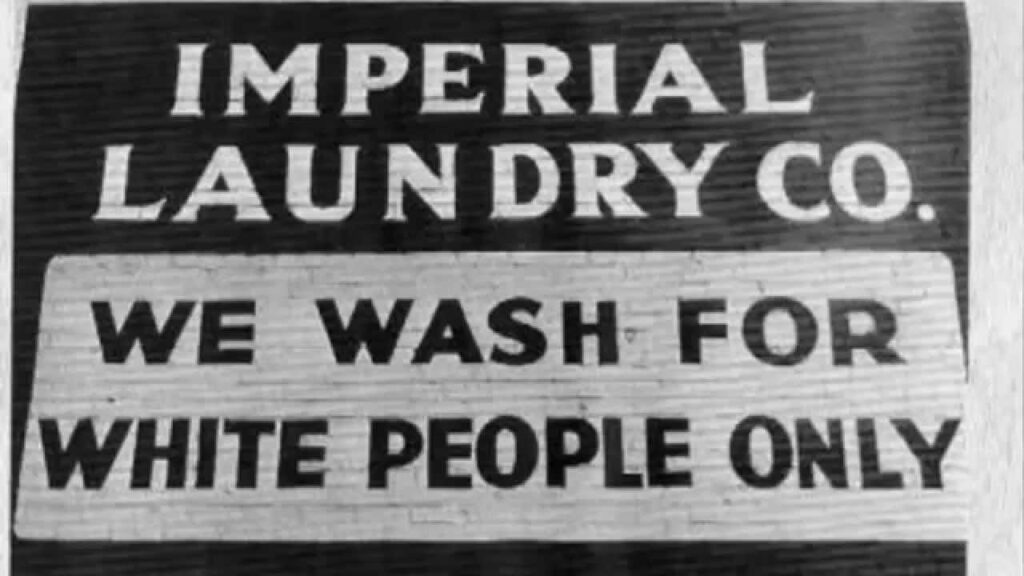

HORNE: To put it mildly. It wasn’t a war in favor of antiracism, as suggested by the fact that in New York City in the middle of the Civil War, 1863, you had these so-called anti-draft riots that are portrayed in the movie by Martin Scorsese with Leonardo DiCaprio, Gangs of New York, which has remarkable scenes, if you’ve seen that movie of antiblack racism and people being immolated and burned at the stake and lynched from lamp poles, etc. This is in New York City. This was not the Deep South. So the Civil War, as we know well know, fortunately, leads to the liberation of enslaved Africans, but at leads directly into the construction of a then Jim Crow regime, that is to say, an apartheid regime, as segregated regime, which then only erodes beginning in the 1950s under enormous international pressure, which is when I come into the story in St. Louis, Missouri.

JAY: Which is where we started.

HORNE: Exactly.

JAY: Let’s go back to Civil War period more, though. From what I understand–and my understanding is pretty thin about this period, but that part of the issue was that this need for wage labor in the North, that elite was also contending with the very powerful elite in the South, which actually may have even had more power over American national politics than even the Northerners did, even though the Northerners represented the kind of new productive forces that were exploding.

HORNE: Yes. And it’s even more complicated than that, in a sense, because as already noted, the slave trade itself was financed from places like New York.

I should also mention that Baltimore was an epicenter of the slave trade. There was a firm in Baltimore, which I mention in my book, The Deepest South: United States, Brazil, and the African Slave Trade, that can take major responsibility or discredit, depending on how you look at it, for the fact that there are so many people of African descent in Brazil right now. So you had forces in the North–.

JAY: Just to add to the Baltimore story, just about four or five minutes from here, Fell’s Point, I’ve seen pictures where there are actual storefronts where there was a point where even though Maryland was a slave state, if I’m correct in my understanding, the majority of blacks in Maryland were actually free blacks, but that there was such a need at a certain point for slave labor that they had storefronts where people could come and sell their slaves to these stores that were then shipped down to the South and that there were a lot of kidnappings–that movie 12 Years a Slave, where they would kidnap these free blacks in Maryland and sell them into these stores down South.

HORNE: That was a real problem, the kidnapping of free Africans–not only kidnapping of free Africans, but say if Britain was heavily dependent upon Negroes in terms of their fleets, their commercial fleets, and so in terms of trading with United States, when they were coming into U.S. ports, say, Charleston, for example, oftentimes in Charleston, South Carolina, there were laws passed that would try to keep these free Negroes from getting off British ships to come into Charleston, because it was thought that they set a bad example because, you know, they had money oftentimes, you know, they were free individuals. That was seen as a bad example. But if they had the temerity to get off the ship nonetheless, they could be kidnapped and wind up working in a field in Louisiana sooner rather than later. And this is part of the tension between London and Washington that continues after 1776.

In fact, if I’m allowed to mention the dates, in a few weeks from now, in August 2014, there will be the 200th anniversary of a remarkable historical episode, although I don’t think it will be marked in most of the mainstream media. (I just pitched the idea to one of your producers.) And that is to say that in August 1814, during the War of 1812, which, by the way, was marked ceremoniously in Canada, but somehow was not marked here, because part of the purpose of the war of 1812 was for United States to seize Canada–.

JAY: Yeah. Well, Canadians tend, rightly or wrongly, think of that as the one real victory other than world hockey over the United States.

HORNE: Well, they have a point. And one of the reasons the United States wanted to seize Canada was because Canada had become a sanctuary for fleeing Africans. And London was not allowing the return of this property, this runaway capital to the United States of America.

But in any event, August 1814, during the War of 1812, the redcoats sacked and plundered Washington, including the White House.

JAY: And burnt down the White House.

HORNE: Absolutely they did. And in an early form of reparations for enslavement, they were joined by enslaved Africans in Washington, D.C., who were stealing dishes and the silver, etc., as the five foot four inch bookish president, James Madison, fled into the streets of Washington with his gregarious spouse, Dolly, in tow, one step ahead of the posse, that is to say, the Negroes fleeing after them trying to catch them and exact some revenge. I don’t think it’s going to be marked in United States, although it’s a heroic episode in black history. Whenever I tell a black audience about that, I can see the glow on their faces, ’cause the way this history’s portrayed in the United States, either the black people are absent or they’re chumps. That is to say, either they’re not there or they’re just doing whatever the master tells them to do, like some sort of robot or something, because if you tell the real story, it’s inimical to the glorious, uplifting propagandistic narrative that is so prevalent nowadays.

JAY: Okay. In the next and final segment of this series of interviews, we’re going to talk about, again, today and how this history weighs on people’s minds today, how whiteness was so important in the whole American narrative and how it reflects itself today. So please join us for the concluding episode on this series of Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

[simpay id=”15123″]

“Gerald Horne is an American historian who holds the John J. and Rebecca Moores Chair of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston.”