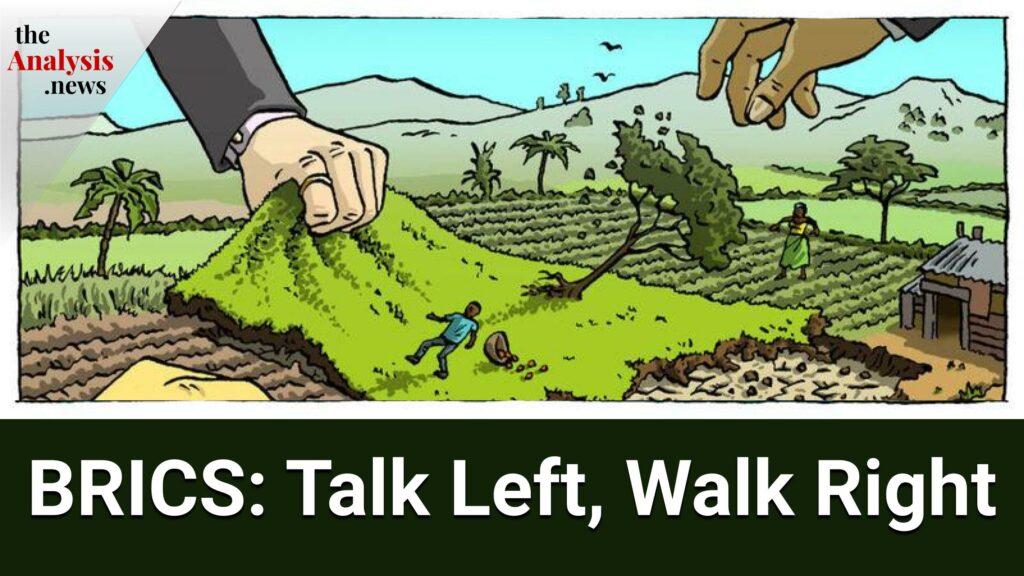

In part 2, Patrick Bond broadens out his analysis of the BRICS countries engaging in what he terms “talk left, walk right.” He explains the economic theories of “accumulation by dispossession” and refers back to the aims of the Non-Aligned Movement of 1961 and the spirit of the 1955 Bandung Conference.

BRICS: An Anti-Imperialist Fantasy and Sub-Imperialist Reality? – Patrick Bond (pt 1/2)

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m Talia Baroncelli, and you’re watching theAnalysis.news. You’re watching part two of my in-depth discussion with political economist Patrick Bond on the BRICS countries. If you haven’t watched part one, I’d recommend that you do that one first so that there’s more continuity and then come back to us here.

We really rely on your contributions to make this content, so it would be great if you could make a small contribution by going to our website, theAnalysis.news, and hitting the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. We really appreciate all of your contributions. You can also get onto our mailing list via our website, theAnalysis.news. Like and subscribe to our podcast wherever you listen to your podcasts, whether that be on Spotify, Apple, or even on our YouTube channel, theAnalysis-news. Make sure when you’re on YouTube, you hit the bell; that way, you’re notified every time there’s a new episode. See you in a bit with Patrick Bond for part two.

Joining me now is Patrick Bond. He’s a political economist and Professor of Sociology at the University of Johannesburg. He directs the Center for Social Change. He’s also the author of numerous books, including BRICS: An Anti-Capitalist Critique, which he wrote together with Ana Garcia. It’s really great to have you here today, Patrick.

Patrick Bond

Thanks for the chat, Talia.

Talia Baroncelli

At the beginning of the interview, you were speaking about Samir Amin. He’s a theorist on uneven development. I think it would be the right time to speak about a capitalist critique and political economy theory since we’re talking about transfers of wealth from the Global South to the Global North and the creation of global value chains.

I know your work has been incredibly influenced by political economist David Harvey. David Harvey, in his book The New Imperialism, speaks about accumulation by dispossession. When capitalism essentially goes into overdrive because it can’t find new territory to extract resources from, it essentially puts a lot of pressure on the people who are suffering from these value transfers and from the extraction of resources. Capital has nowhere to go in those instances.

Maybe you can use this analysis right now to explain what happened with the integration of countries in the Global South into the global economy in the ’70s and ’80s when they were absorbed into the economy and then eventually also creators of surplus, but then this capital had nowhere else to go, and there was increasing dispossession. I think it would be the right moment to speak about how these theories actually play out in real life.

Patrick Bond

It’s always great to be able to review the evidence and then see where you may need theoretical framing because you’ve done it very well. The earliest of the, I think, theorists that described imperialism at the time, particularly using colonial power, was Rosa Luxemburg, who, in 1910, in The Accumulation of Capital, really found that the surplus transfer was capital meeting the non-capitalist.

Now, there were other theories of imperialism because Europe was in chaos. Vladimir Lenin wrote a great pamphlet in 1916 about the inter-imperial rivalries. Others like [Nikolai Ivanovich] Bukharin and [inaudible 00:03:22] drew on John Hobson. Many of these important early 20th-century theorists could identify that if you run out of space for your capitalist class, well, they’re going to need their colonial hinterland. Then they’re going to get into conflicts over how that occurs. I think it was Luxemburg framing it as capital against the non-capitalists, against traditional societies, against nature by depleting non-renewable resources, against matriarchal systems, or against states that were emerging, which we now know is a process of privatization.

David Harvey, The Accumulation of Capital, and for disclosure, he was my doctoral advisor, picks that up and brings it up to the 21st century in which, as you say, we’ve seen this sort of layer emerge. Immanuel Wallerstein calling it a semi-periphery because it’s not really in the South. These are particularly in the ’60s and ’70s when these theories were emerging. You could see the U.S. having client states in Israel, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the Middle East, and Iran at that time before 1980, or Brazil and some of the Latin American countries that had coups that were organized or supported by the U.S.

Now, the main point about that layer is that even in the ’70s, when new industrialized countries were coming up and then China in the ’90s with its liberalization, they became attractive sites for Western multinational capital. The value chain you mentioned, in which the dirty work of picking out the raw materials from Africa gets done by Chinese companies who put the products together in their big factories on the east coast of China; they then sell it to the West, making the amplification of the exploitation and this unequal ecological exchange much worse. The Chinese firms, as far as I’ve seen them operate, are much harder to contest. They’re much more repressive and ruthless. We don’t have the systems, for example, of corporate social responsibility or filing lawsuits that we would have if we were fighting a U.S. company, especially British companies or government companies. These are the dilemmas we have in looking at the BRICS layer of companies.

Let’s say if you use a Marxist framing of over-accumulation tendencies, they overproduce. Like the West, China is the most overproductive, with roughly 30% overcapacity in most of their main industrial sectors. Well, they do need to, as they’re putting it, they need to go out. The spatial fix they need to move. The Belt and Road initiative was the vehicle for that. That means they’ve run into the kind of terrain of poor countries. Maybe most spectacularly, we saw Sri Lanka default, unable to pay China and then having to turn over a port to Chinese management.

Now, the dilemma is that when you move out of these processes, you’re not getting a new kind of infrastructure. You’re still under those sorts of pressures, getting neocolonial systems. The theoretical forces of extractivist capitalism, accumulation by dispossession, are actually being amplified by the BRICS companies. That’s one of the most dangerous things when we look at here in South Africa, the kind of BRICS infrastructure.

At the moment, the BRICS New Development Bank is part of this, aimed at exporting coal. Chinese locomotives ended up in a corrupt relationship or the special economic zones that China had been very active in; these all reflect, at a deeper theoretical level, some of the capitalists in the world being exuberantly extractivist and super exploitative.

Unfortunately, although, of course, the Western companies are there, the big oil companies are certainly all around Africa; it’s the Chinese, Indian, Brazilian, Russian Wagner Group as part of that, and of course, the South African that are doing some of the worst damage in Africa. It is sad. Let’s call it an exhaustion of the various possibilities that capital always explores. To have a spatial fix to move the problem around. To have a temporal fix, which is to use finance to pay later while you consume now using the credit system.

Now, accumulation by dispossession is what we would call the shifting of the problem, the stalling of the problem through finance and credit and the stealing of those management techniques for the capitalist crisis. Once you run out, then you’re going to start seeing military conflicts logically emerge as logics of territorial conflict take center stage and the internecine battles between capitalists then reach the point where it looks like 1914 all over again.

Talia Baroncelli

How do you differentiate between the sub-imperialism you’ve been speaking about, how that’s reflected in the BRICS, and what’s called inter-imperialism within this capitalist system? Is there much of a difference between the two? Is it just a theoretical term, or would you say that it’s substantially different?

Patrick Bond

Yeah, it could be semantic at one level, which is where I see a lot of comrades who are worried about the Russian invasion. For some, like Boris Kagarlitsky in jail in Russia, the logic of Putin’s invasion was his own legitimacy crisis at home. I’ve seen other good arguments. Ilya Matveev makes the argument that till 2014, with the Crimea occupation, you could have logically described Russia as sub-imperialist, but then it became inter-imperialist. There are a lot of theorists out there who would like to see Russia and China as inter-imperial rivals because it shows, in a sense, that the organic decline of an empire, the U.S. empire, is underway. We’d all probably appreciate the decline of the U.S. and its malevolent power, its military activities, and its power over economies, social, cultural, and all sorts of factors.

However, I regret that I don’t think we’re at that level where we can call China, even with a $240 billion-a-year military budget, anything as powerful as the U.S. to qualify as inter-imperial. The U.S. has roughly $850 billion. If you put all the pieces together of annual spending on the military, they have more than 800 bases around the world, and China has only a couple.

If you look at the mismatch between the imperial powers, even with Russia having very sophisticated long-range missiles, as they say, it’s difficult to put them in the same category as the U.S. But maybe more importantly, the sub-imperial layer, which I think I could call Russia, still implies deputy sheriff or regional [inaudible 00:10:13] duty. The dilemma is that they go rogue, and the U.S. has always had iron states that went rogue. You could think of [Ferdinand] Marcos in the Philippines, who had to be let go when there was social unrest or [Manuel Antonio] Noriega in Panama. There are many cases where a dictator who had served U.S. interests doesn’t anymore.

For Putin, he’s sufficiently strong that he could be rogue in Crimea with the invasion in 2014 and then invade Ukraine in 2022. His argument is partly that he was provoked. Of course, we know the argument about NATO expanding eastward, but also that the United States and Janet Yellen, the Finance Minister, the Treasury Secretary, and all of the associated central banks and finance ministries who grabbed $650 billion of Russian assets, roughly half from the central bank, half from oligarchs, that they went rogue. In other words, if you’re in imperialism, you play by certain rules: property rights and financial market rights are sacrosanct.

We’re looking at a breakdown of all sorts of systems in which imperialism and sub-imperialism, as Amin put it, this cooperative antagonism in which they are in the same system, but they have somewhat different interests and run out of control.

Because you mentioned Samir Amin, we’ve just had a very important celebration of his work in Rio de Janeiro with networks that include Progressive International, international workers and people. Samir thought the Fifth International would be a critical development from below. I’m not sure we’re anywhere near the point where the World Social Forum could be resurrected. It was the major force for bringing progressives around the world, based mostly in Brazil and a little bit in other countries. Then we had a few other initiatives of, let’s say, less far-reaching sort over the last couple of decades. Progressive International may be one of the most important. There’s the Tricontinental project, run by Vijay Prashad and his allies.

There are very interesting projects out there that can do this, but I think they’re very divided. For example, there is a group around Vijay and plenty of others who would appreciate the BRICS emerging now as a multipolar alternative to that unipolar U.S. I think that’s where it’s critical to make the interventions where the data, the experiences, politics should tell you that tyrants from the BRICS plus countries because most of these Iran, Saudi Arabia, U.A.E., Egypt are tyrannies. If you combine that with their carbon addiction, they are not going to be a progressive, multipolar alternative to Western unipolar systems.

When you look at multilateral institutions, and you see how closely the BRICS fit again and again from the UNFCCC to financial arrangements and trade, you don’t find an anti-imperial multipolar alternative; you find sub-imperialism.

It’s in all those respects that I’m hoping that we get a lot more friendly debate among comrades to ask the tough questions: who are your allies? What kind of social, class, and environmental analysis are you bringing? If you, for some reason, think there’s a multi-polarism that’s coming out of the likes of the BRICS plus when what I think we all need is Bill Fletcher, a U.S. labor and African American leader, who has said, “We need a non-polar world. We need one in which the values of society and environmental survival are finally respected.”

Talia Baroncelli

Well, I did want to ask you about how the Russian invasion of Ukraine is being perceived in South Africa. Before we get there, just one other theoretical question. Now that we’re talking about international norms, many international legal scholars who have this third-world approach, more of a Marxist approach to international law, would argue that concepts such as sovereignty, jurisdiction, and nation-state all come from a very specific European trajectory, which is bound up around industrialization, value extraction, and capitalism. So, it is a capitalist international legal order. Some of them would argue that as a result of that and because of colonialism and all the violence that it entailed, you would need different legal norms and different bodies of law for so-called developing countries or weaker nations in order to compensate for a lot of those disparities and unbalanced power relations. How would that play out, and do you think the BRICS would support those arguments?

Patrick Bond

Well, the dilemma is that property rights in Western law, going back to common law, have been the central force. In the mid-19th century, this was then codified in different constitutions. South Africa was one where, regrettably, not only were property rights very poor, but in 1996, when Cyril Ramaphosa, our current president, managed the constitutional process, they also gave corporations human rights, and they gave them juristic personhood as it’s called. So the dilemma is that we get sucked deeper and deeper into those Western liberal norms, which are liberal politics but neoliberal economics.

Samir Amin’s great statement about the BRICS is that they will often argue with the geopolitical agenda of imperialism. They’ll raise their concerns as leaders of these emerging markets. However, they will not challenge economic neoliberalism. So, for Samir Amin, the BRICS could only walk on one of the two legs that are going to be required for doing something different. I fear that’s the case in a place like South Africa, where the power relations that made this country the second most unequal in the world at the time we were liberated from apartheid actually worsened on class lines because we are now the most unequal because our inequality got much worse. So did poverty, and so did unemployment. These all soared. Our ecological degradation has been extreme since 1994 with much liberalization of the mining sector and all sorts of, let’s say, nudge-nudge, wink-wink irregulatory processes.

Now, that means, I think you’re in a dilemma, especially if you come from critical legal studies traditions in which you’re concerned that you can maybe take Western human rights norms, Western International Criminal Court, and maybe some climate court at some point, and you try to overlay those onto a place like South Africa. Well, you’ll come up with incoherence. That’s what our own constitution has shown again and again. We have very strong rights for people to have healthcare, housing, and education. Yet again and again, when we’ve seen these play out in the Constitutional Court at the top level, we’ve seen the politics from below squashed by orthodox legal thinking that rests upon two premises. One is that progressive realization of those rights is possible. You can do a little bit more each year. Secondly, you have to do it within available resources. That means you go to the Treasury, and the Treasury is under the thumb of the IMF, literally. We’re engaged in structural adjustment and austerity that is brutally bad, including in the next month’s budget. In that sense, all our socioeconomic rights are just trumped— it’s a bad verb, but it works— by the rights of property and the rights of neoliberal managers in the Treasury who say, “No, there’s just no money to give you.” The health care, the water, the housing that you’re ostensibly guaranteed.

So, yeah, I would question whether our Western norms of liberal, let’s say constitutionalism, political parties that have certain kinds of capacities, but we’re going to be only testing them when ANC, the ruling party, loses sufficient power that it becomes competitive. They may not work here. I would say we need to transcend. We need to, in a sense, go through the RICE framework that was given to us in our liberatory zeal in 1996 with this new constitution and find much more concrete strategies. We usually call this commoning. So if your water is disconnected, your electricity is disconnected, well, you’ll find some comrades in the community who will come in and reconnect you illegally. And 85% of Soweto, the big township here in Johannesburg, is illegally connected to electricity because of informal electricians who can get around the various metering systems. It is the same for water.

Now, these are the, let’s say, desperation tactics of mutual aid when a liberal economy and a liberal political system don’t deliver the goods. I would love to see more of the other activists in the BRICS, like the movement of the Landless Workers’ in Brazil, who occupy land, even if it’s privately owned, who have basically the same kind of constraints. Their activists know that property rights and liberal norms and values from the West only go so far when you are genuinely desperate.

Talia Baroncelli

Is it accurate to say that these norms are already being applied unevenly or selectively? Because if you look at the U.S., for example, they’re instituting more protectionist measures in certain contexts. For example, in their de-risking with China and the Chip War, so to speak. So it seems like there might be good reasons for them to do that. Would you say that they’re already being selective with the application of these laws while at the same time ensuring that WTO, World Trade Organization standards and trade standards are still being applied for everyone else?

Patrick Bond

Yes, that’s right. The need to get outside the WTO we experienced in 2001. If you recall, there was a meeting in Doha which came after the Seattle meltdown of the WTO. So they needed to re-legitimize that work for us because of the demand from South Africa, where we have, out of about 60 million people, about 8 million who are living with HIV. At the time, it was around 5 million in 2001. The medicines, the antiretroviral drugs, cost about $10,000 a year. A very small sliver of the people who are living with HIV could get these medicines and live long, healthy lives with the ARVs.

As a result, there was a move to get intellectual property removed, as I mentioned, with COVID-19, and that was successful at the time. The balance of forces was much more in our favor. What it did was allow generics to be made for the ARVs, and those were then rolled out through the public sector. As a result, mainly because of activists at the Treatment Action Campaign, really mobilizing the society, mobilizing the world community in solidarity, those medicines for free that used to cost $10,000 a year allowed the life expectancy to rise from a low of 52 in 2004 to 65 at the time of COVID. Now, that’s the kind of, let’s say, commoning in that case of intellectual property over medicines that we could see as breakthroughs. So it’s not impossible. It’s a very rare case of actually going around the WTO restrictions, trade-related intellectual property restrictions.

So what you’re saying, I generally agree with. There has been way too much emphasis on playing within those rules, and attempts to reform them, as we saw with Ramaphosa and Modi trying to get the exemption on COVID medicines, are very, very difficult. The major reason, I think, is the U.S. has such a formidable starting point, which is property rights, but also, they bring a battery of lawyers and lobbyists. Their corporates are always extremely active, especially when they bully. They use diplomacy in the WTO to shout down any cheeky Third World delegate. I’ve seen that happen.

There was a fantastic man from Uganda, Yash Tandon, who regularly, he’s written about it in great detail, would try to challenge Western power within the WTO and did so very successfully in Seattle in 1999. But at some point, if you do that, if you’re in the UNFCCC, like Pablo Solón, [Inaudible], or Lumumba Di-Aping, three very famous negotiators from the South, each time the U.S. says to your president in your country, “[inaudible 00:22:45] out of our face. Take him off your delegations.” So, yeah, these are, let’s say, symptoms of imperial power. The WTO has worked with some glitches, but generally, it has worked very well— the World Bank, IMF, and the UNFCCC, as well as the imperialist vehicles. Regrettably, BRICS sits into these institutions and systems as allies of the West rather than critics.

Talia Baroncelli

The very last BRICS summit in Johannesburg had an elephant who wasn’t in the room, and that was Vladimir Putin, Russian President. He obviously wasn’t able to attend because of the ICC warrant that’s out against him. There’s been a lot of criticism of South Africa for not condemning the invasion outright. Some people would argue that it’s unfair to criticize countries because there is this international legal system and criminal system that’s in place, which doesn’t really work. The U.S. was never held to any sort of standards of accountability for its invasion, its unilateral, illegal, illegitimate invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan. To hold Russia to that same standard is very hypocritical, given that the U.S. was never held to that standard. How is the perception of the war playing out in South Africa, at least from your perception of it?

Patrick Bond

Yeah, well, you’re right exactly about this problem of hypocrisy at the International Criminal Court. Tony Blair, a Britain member, should have been prosecuted. In the case of Brazil, also a member of ICC, Lula said to Vladimir Putin, “Oh, you can come to the G-20 when we host it next year.” Then he backtracked from that.

On reflection, these are constitutional crises because, as we saw once here before, in 2015, [Oman] al-Bashir, the dictator from Sudan, was on that same ICC warrant and had to be flown out of the country very quickly before our own courts here in Johannesburg could quickly get that arrest warrant to comply with the ICC warrant. That was what we were expecting. So when Putin then decided not to come, just at the time when an African delegation led by Cyril Ramaphosa was visiting Moscow, he then signalled, and then Ramaphosa to kind of go to the other BRICS leaders and say, “Well, he won’t come. He’ll send Sergey Lavrov.”

You can imagine the chaos and, let me say, the distraction effect. It was compounded by two other factors partly related to Ukraine. One was the war exercises that had been long planned with China and Russia, naval exercises in February on the one-year anniversary. The second factor occurred in December when the U.S. ambassador had claimed, and he said, “I’d bet my life on it,” so he might have had some CIA surveillance to give him that confidence. He said, “Arms were uploaded to a ship that was snuck into the harbor in Cape Town, Simon’s Town.” And that particular chaos, let’s call it the Lady R, the name of the ship, the Lady R scandal, also has distracted us. Even still, to this day, we don’t know what really happened with that ship and what was being unloaded. Was it AK-47s to be used in Mozambique, as the Defense Minister implied? Or were there other old ammunition stocks that were being brought back and forth with their private dealer? It’s all very murky because we haven’t got access to South Africa’s report. The U.S. is trying to heal those wounds and the main reason is because the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act comes up for renewal, and South Africa is the main beneficiary. It’s mainly Mercedes Benz, the German auto company that gets huge tax benefits from being part of AGOA. The tariff rate for importing cars from South Africa to the U.S. is very low.

Also, BHP Billiton is the biggest mining house in the world with its steel and aluminum exports to the U.S. Petrochemicals, some of the deep mining, and the highest electricity-guzzling products we have, I think, should actually not be given this AGOA exemption. So they come into the U.S., and they’re basically very cheap. That’s the big debate going on even as we speak over whether the U.S. has let off the pressure.

Unless Donald Trump wins in late 2024 and in 2025 when AGOA gets renewed, and he just says, “No, I won’t have South Africa in AGOA. It’s getting too many benefits,” which is quite likely if he does win. This is one of those ways in which imperialism is trying to, let’s say, smooth the rough edges with sub-imperialism in the U.S. and South African terrain.

You’re absolutely right. The context is one in which, geopolitically, it’s a very fluid situation. South Africa initially condemned the invasion at the end of February, but then in early March, some say because the ruling party got a 10 million rand or about a $500,000 contribution from a major oligarch, Viktor Vekselberg, who co-owns a Manganese mine here and that kept that ruling party’s finances barely afloat.

Those are the sorts of questions none of us really have clear answers to. What motivated that U-turn by South Africa to be neutral, to say we won’t condemn the invasion because the BRICS always rhetorically say we respect sovereignty, we respect international borders. Yet on this very clear occasion of the borders being violated, our president and foreign minister continually saying, “No, we’re going to play neutral. That way, we can be honest brokers.”

Is there a plausible case that South Africa could be part, perhaps with Lula in Brazil, perhaps with Erdogan in Turkey, of some delegation that finally settles a peace deal? It’s not impossible. The plausibility comes from Cyril Ramaphosa having a role like that in Northern Ireland, actually, where I was born in Belfast, in trying to sort out what was called the Good Friday Agreement. This is why our politics are quite, let’s say, hard to predict because we don’t quite know whether Cyril Ramaphosa will stay in power through the next election year, which is next year. He was threatening to resign apparently last December because of the financial scandal I mentioned. The dilemma, then, is whether we can get social forces into play.

I should confess something I should have said at the outset. The position that I’m arguing is a lonely one on the South African left. The reason is for lots of complicated, let’s say, diverse and, in many cases, corrupt reasons. The five major groups that we would say normally would represent the interests of the popular forces in our society, the five largest, one is a political party that gets 10% of the vote— Economic Freedom Fighters. Another is the rump of the ANC, which the populous calls Radical Economic Transformation. A third is the South African Communist Party. Fourth is the largest trade union federation, the Congress of South African Trade Unions. The fifth is the biggest single trade union, although it’s not in COSATU, it’s the National Union of Metalworkers. All five of these forces are not only pro-Putin openly and pro-BRICS openly, they’re now also pro-coal. The kinds of protesters that we had in late August against the BRICS were extremely, let me be humble and self-critical, a motley group of environmentalists, community groups that are disaffected, Kashmiris who are here in exile because they don’t like what [Narendra] Modi was doing. We had Bangladeshis who didn’t like what Sheikh Hasina, their leader, was doing. We had all manner of other, let’s say, forces emerge, and they came largely to the field in Sandton, the financial district, about 4 km away from the actual site of the summit.

We’re hoping a BRICS from below network can show a more clear, firm, and more formidable force in the future. But at the moment, as I said, with the main center-left forces in our society quite explicitly pro-BRICS with the lines of argument that my enemy’s enemy is my friend when it comes to this hatred of U.S. imperialism, and with the sense that maybe Putin has some historic nostalgic relationship to the Soviet Union and its support for the anti-apartheid movement, even though we know Putin really was very, let’s say, insulting of the USSR’s traditions, especially Lenin. In spite of very weak trade relationships between Russia and South Africa and the corruption and the nuclear deal, the role of the Wagner Group in Africa, all of these factors that should make our center-left forces more progressive and internationalist and supportive of the Ukrainian working class, we have failed to make the argument adequately to bring them to a kind of critical standpoint that I’m articulating.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, Patrick Bond, political economist, professor at the Sociology Department of the University of Johannesburg and director of the Center for Social Change, it was really great to have you on to discuss these issues, and I have a feeling we’ll be speaking again very soon about social movements in South Africa and Debt for Climate, which I think are very important issues. It was a pleasure to have you on today.

Patrick Bond

Great to be with you, Talia, and with theAnalysis. It is the best network I have seen. Thanks.

Talia Baroncelli

Thank you. Thank you for watching theAnalysis.news. If you enjoyed this content, please don’t hesitate to go to our website, theAnalysis.news, and hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen, and we’ll see you next time.

[powerpress]

[simpay id=”15123″]

Patrick Bond is a Distinguished Professor at the University of Johannesburg Department of Sociology, where he directs the Centre for Social Change.