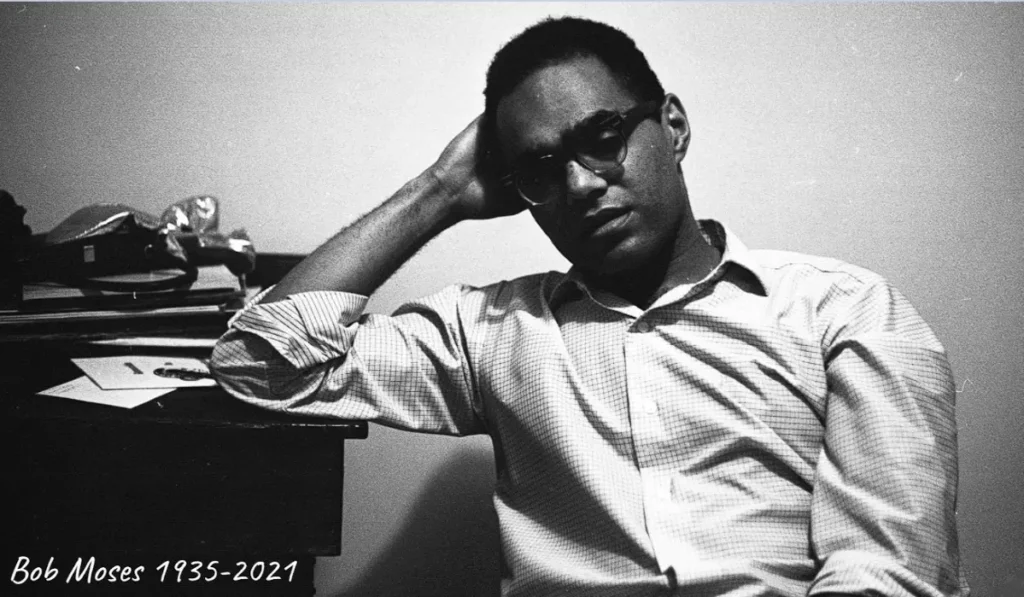

Sad news that Bob Moses, a leader of the civil rights movement, died on July 25, 2021. We commemorate his work with a replay of his appearance on Reality Asserts Itself with Paul Jay, first released on June 20, 2014. Mr. Moses was a brilliant educator and an organizer. He begins his story from growing up in Harlem to becoming a main organizer of the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer project that helped register black voters in the Deep South.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY : Hi, I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And welcome to a new edition of Reality Asserts Itself.

Robert Parris Moses became one of the most influential leaders of the black civil rights movement in the 1960s and afterwards. Martin Luther King called his grassroot organizing an inspiration.

Moses was one of the leaders of the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer project. He was also an organizer for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in 1964.

And we now have the pleasure of Mr. Moses joining us in the studio.

Thanks very much for joining us, Bob.

BOB MOSES, EDUCATOR AND CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST: Right.

JAY: And I should say Bob Moses, ’cause I think that’s how you’re known.

MOSES: Right. Yeah.

JAY: Bob Moses is an educator and civil rights activist. During the 1960s, he was the field secretary for SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, as well as the main organizer of the Mississippi Freedom Summer project that helped register black voters in the Deep South. He was also an outspoken critic against the Vietnam War. From 1969 to ’75, he worked as a teacher for the Ministry of Education in Tanzania. In 1982, he received a MacArthur Fellowship, and he used those funds to develop the Algebra Project, an organization aimed at improving math education in poor communities. Bob is also the author of Radical Equations: Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project and coeditor of Quality Education As a Constitutional Right: Creating a Grassroots Movement to Transform Public Schools. He’s also earned a master’s in philosophy from Harvard.

Thanks very much for joining us.

BOB MOSES, EDUCATOR AND CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST: Right.

JAY: As you might know, our viewers at home that watch Reality Asserts Itself, we start with a biographical segment and then move into some of the issues. I think in this case we’re going to mostly be biographical, because of all the major issues of the civil rights movement intersected with Bob’s life.

So let’s start from the beginning. Talk a little bit about where you were born. And off-camera you were telling me just weeks after you were born something erupted.

MOSES: Yeah. So there was a riot in Harlem.

JAY: And this is 1935.

MOSES: Nineteen thirty-five, in the middle of the Depression. I don’t know what the immediate cause of the riot was, but the result of the riot was the city decided to put up some housing for black people in Manhattan. So I think it was 1937 the first housing projects in New York City were put up right across the river from the Yankee Stadium. In those days, you know, the New York Giants were also in New York, and their Stadium was in Manhattan around 157th, 158th Street and Eighth Avenue. So the projects grew up between the Yankees and the Giants. So that’s where I grew up, in Harlem River Houses.

JAY: And what did your father and mother do?

MOSES: So my father was a janitor. He worked at the 369th Armory. It was a good job in the ’30s. It was a steady job. It was steady work. Right? It later was frustrating to him. And my mother was raising us. I was in the middle. I had an older brother. He had been born in ’33. And then my younger brother was born in ’41.

JAY: And was your father at all politically involved? What was his political thinking? And your mother.

MOSES: So my parents had done high school, but neither one had gone on to other kinds of education. I think my father was kind of trapped by the Depression and in terms of his own education, though I don’t know whether he really had a goal to continue his education after high school. His two brothers both–one became a professor of–actually started the Architectural Department at Hampton, and his oldest brother became a lieutenant colonel in the United States Army. So his path ran into–in one way of thinking about it, ran into the Depression. Right? And then, when he got married–.

JAY: As you grew up, did he vote? Did he talk about politics?

MOSES: Well, he–. Yeah, he talked about the man in the street. He was a kind of philosopher who liked to visit, and I was a kid who liked to hang, right? And so if he said, you know, are we going to go see a dog about an elephant, you know, I went. Right?

JAY: See a dog about an elephant?

MOSES: Yeah, he had these funny ways of saying where he was going, right? He was fun to talk to.

JAY: What did that mean?

MOSES: It just means he was going to go talk to some people. Yeah.

So, anyway, he really, I think, looking back, helped me understand how to read people. He was always talking to me about the person we had just talked to. Right? And he had a way of thinking about whether people lived up–whether what you saw was what was there and whether what you heard was what was real. Right? And so he was always, you know, engaging. He was really in some sense gregarious. Right? He liked to talk to people. His father had been a minister. Actually, my grandfather was vice president of the National Baptist Convention, a Garvey supporter, in the 1920s. Right? And so he had grown up in a kind of environment. But we didn’t really hear that as we were growing up. It wasn’t active.

JAY: So he talked about Pan-Africanism or not? It wasn’t part of his conversation.

MOSES: It wasn’t part of the conversation at home.

JAY: And the neighbourhood you grow up in, was it all black? Mostly black?

MOSES: No, Harlem in those days was all black. Harlem River Houses was all black. I think there was one interracial couple in the projects. Black, working-class. So, I mean, most everybody, a lot of two-family homes. There were single mothers, but there were a lot of two-family homes, mostly two-family homes.

JAY: But it was a real community.

MOSES: It was a real community up through World War II. Right? Actually, we organized–we had–Mr. Plummer was a–he actually was a pitcher in the Negro leagues, right, doing during the ’20s, I guess, ’30s. But he organized us into a baseball team. So we were the first black baseball team in New York City, moving around on the trains and the buses thirty-strong, right, competing in the White leagues. So, you know, they had these baseball leagues. And we were the only black team, actually. This is before Jackie hits Brooklyn. You know.

JAY: Right, Jackie Robinson.

MOSES: Jackie Robinson, yeah. My father, actually, who was a Mel Ott fan, right, New York Giants–Mel Ott was the right-fielder. So when he told me–I was young kid–that he had to switch to Brooklyn and pick up Jackie, I knew something really monumental had happened, right, ’cause–.

JAY: And when–I mean, I guess it’s obvious as you grow up that there is a black world and there is a white world.

MOSES: Well it hits me first–. Uncle Bill decided he was going to enter into the competition for Virginia’s pavilion at the world’s fair which happened in New York City, I think in 1939. Right? And so he disguised his entry. And when it won, they printed his name in the paper.

MOSES: This is what, to build the pavilion?

MOSES: Bill Moses, he’s teaching at Hampton Institute. He’s an architect, right? So he designs a pavilion for Virginia for the world’s fair.

And so, they say in the paper, “Mr. William Moses”. You know, he had just disguised his entry, right? So then they find out he was black and withdrew it. Right?

I’m a young kid. He comes up. He and my father were pretty close, right? So he comes up. They spend three days just drinking and cooking, right, and talking about what this means.

JAY: How old were you?

MOSES: So I’m five. I’m a young kid, right? But I liked to hang, right? So I’m hanging in this little kitchen, watching my father and Uncle Bill go over and over and over and over this story.

JAY: Are they angry?

MOSES: They–it’s not bitterness, right? It’s–they’re appreciating in some sense the situation in this, that–this country and what happens, the conundrums that happen, right? But Bill, of course, he knew once he submitted it that if it won, in some sense he was probably not going to get it, right? I mean–and so–because he went to all that trouble. But he wanted to know that he could win. Right?

JAY: So how do you internalize that? And as you grow up, how does your thinking develop on–?

MOSES: So I’m pretty ensconced in my black community, right? Basically right through elementary school, I go to PS 90. It’s an all-black elementary school. We have white teachers first and second, third grade, and then from then on we had black teachers.

What happens is I get, I think, caught up in what I now think of as a national move to find talent. So Conant, remember, who’s president of Harvard from ’33 to ’53–and he gets to be president of Harvard because of the Depression, right? So the whole country is looking at its leadership, and Harvard decides to change the nature of its presidential leadership. They hired Conant. Chemistry professor. He decides that he is going to change the nature of who goes to Harvard, right? So he gets Henry Chauncey, his dean, to get a test. That’s how the SAT first comes into the national picture. Chauncey uses the SAT, and Conant says, we’re going to actually get public school students into Harvard, ’cause before, they had to get in through the college board, which had an exam that the Ivy League students and the, you know, institutions and the private schools had arranged. So you had to go to private school, really, to pass that test to get in. So all through the ’30s the Ivy leagues begin to get public school students.

Then you have World War II, and Conant sets up ETS, the Educational Testing Service, and then also looks, I think, begins the notion we need to look for talent. Right?

So I’m graduating from the sixth grade, 1947, PS 90 in Harlem. I’m scooped up and put into a junior high school. They take two kids from every sixth-grade class in Harlem in the South Bronx and put us all together and tell us we’re going to finish junior high school in two and a half years instead of three. Right? But we get some good teachers. I get a German teacher to teach algebra, right? And so my older brother had already passed the test and gone to Stuyvesant. That was an exam school, right? The Stuyvesant Bronx Science and Brooklyn Tech. So I pass the test and go to Stuyvesant. And that’s my entry into the white world in New York City, right? So it’s flipped now. I mean, there are maybe a handful of us–in a school with about 3,000 students–who are black.

JAY: And how old are you?

MOSES: So 1950, 1949, I’m 14.

JAY: And you’re now getting an elite education.

MOSES: Fifteen.

Yes, I’m beginning this–. Well, I think the elite education begins in the junior high school, in the sense that they scooped us up, right, they had special teachers for us, right, at Stuy, right. So we’re beginning to get the sense that, you know, this group of kids are getting attended to.

JAY: We’re going to continue this discussion with Bob Moses on Reality Asserts Itself. Please join us.