Dr. Asoka Bandarage is an adjunct professor at the California Institute for Integral Studies and the author of a new book, Crisis in Sri Lanka and the World. Sri Lanka has had a minuscule carbon footprint, and yet the country is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, coastal erosion, and flooding. She discusses the convergence of existential climate and debt crises in Sri Lanka, the latter resulting from IMF debt restructuring and the lack of a globally coordinated multilateral sovereign debt mechanism that places traditional and private lenders on an equal footing.

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m Talia Baroncelli, and you’re watching theAnalysis.news. Joining me in a few minutes is Dr. Asoka Bandarage. She is the author of a recent book called Crisis in Sri Lanka and the World, which speaks about debt-tracked nations and how the Bretton Woods system continues to impoverish these countries. But first, if you enjoyed this content, please consider going to our website, theAnalysis.news, and hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. You can get onto our mailing list so that you’re updated every time a new episode drops. Also, like and subscribe to our YouTube channel, theAnalysis-news, and subscribe to the show on whichever podcast platform you’re watching the show on. See you in a bit with Dr. Asoka Bandarage.

I’m very happy to be joined by Dr. Asoka Bandarage today. She is an adjunct professor at the California Institute for Integral Studies. She’s also previously taught at the University of Brandeis and Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. and held tenure at Mount Holyoke. She’s published extensively on colonialism in Sri Lanka, and her most recent book is called Crisis in Sri Lanka and the World. Thank you so much for joining me today, Dr. Bandarage.

Asoka Bandarage

Thank you very much for having me. I really appreciate it.

Talia Baroncelli

Your book is very timely because it speaks about the current debt crisis in Sri Lanka. It also contextualizes this debt crisis, tying it back to the Bretton Woods system and to European colonialism, which resulted in the impoverishment of society in Sri Lanka. I think a lot of the colonial, or I would say mainstream portrayals of what’s going on currently in Sri Lanka missed the mark, and they don’t really offer the context that your book offers.

The mainstream narratives essentially say that Sri Lanka has not been following through on its commitments to the IMF or to the World Bank, and that’s why it’s in this predicament. I believe that you have a much different take on that. Why don’t we begin with why you think Sri Lanka is currently in a sovereign bond and debt crisis?

Asoka Bandarage

Well, as you point out, the mainstream analysis is very limited. It focuses on the COVID-19 crisis, the Ukraine war and its ramifications, and local mismanagement, corruption, etc., that contributed to the emergence of this debt crisis towards the beginning of 2022. Those are important factors that played into the crisis. The crisis is much more long-term. As you pointed out, it has to be seen in a global context and also a historical context, which is what I try to do to show that the colonial and neocolonial policies, particularly neoliberal policies, have tethered countries like Sri Lanka into this debt cycle. Although they provide standby loans, they are not meant to extricate these countries from the debt burden and to make them self-sufficient and sustainable in the long term. It is more to maintain the current financial and economic system. Debt plays a very important role in that.

Talia Baroncelli

One thing that was really fascinating to me when I was reading your book was that you problematized this notion of debt and diplomacy to China. A lot of think tankers say that Sri Lanka is in debt because it let China walk all over it and that China has invested in Sri Lanka but, as a result, has been able to create a lot of debt in the country. You actually point out that a lot of the debt is held by private asset managers such as BlackRock and that a lot of the international sovereign bonds, which Sri Lanka has, are provided for by BlackRock. Could you speak about that dynamic as well and how the unregulated asset management financial system has contributed to the debt issue in Sri Lanka?

Asoka Bandarage

These statistics are there, although they are not used in the mainstream analysis correctly. Of the total foreign debt, only about 10% is owed to China, and 48% is due to private market borrowings, which are mostly international sovereign bonds, which means they’re mostly E.U. and U.S.-backed ISDS [Investor–State Dispute Settlement], that more than 80% of the foreign debt is used to western creditors. That is something that is often overlooked.

Talia Baroncelli

Of course. Perhaps another thing that has been overlooked in the mainstream narrative is the agricultural reforms that were instituted in 2019. There were certain agricultural reforms which were, I believe, quite ambitious and even positive: trying to help smallholder farmers or to have a different agricultural system which wasn’t primarily based on the export plantation system. Would you say the portrayal of some of these reforms and how these reforms contributed to Sri Lanka not being able to make good on its debt payments is perhaps an inaccurate way of examining those reforms?

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah, it’s a very complex issue. There was a shift to organic agriculture, which the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration had promised. But it was done very quickly overnight in order to save foreign exchange to not pay out for agrochemicals and pesticides that are being imported.

Now, organic agriculture is no doubt the way to go, but it’s not something that you can change overnight because these small farmers, especially rice farmers, have been encouraged to shift from organic agriculture to the use of pesticides and agrochemical fertilizers over time. They were induced to do that through the neoliberal reform since the 1960s.

Now, suddenly, they were told to switch back to organic agriculture overnight, and that did not work out. It backfired. That was used by certain groups to condemn organic agriculture altogether. Now, they’re back to importing chemical fertilizers and pesticides. It was a very unfortunate experience because something that should have happened over time got enmeshed in this whole debt crisis and debt relief issue.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, maybe this is a good way to speak about the history of colonialism by using this issue of agriculture. Your book speaks about how under British colonialism in the 1830s, there was a different form of agriculture which was forced on the country, which was plantation agriculture. A lot of the other forms of cultivating the land by having different biodiversity and different types of crops side by side were done away with. This new form of agriculture in which goods and certain things would be produced in order to export them to the U.K. and to other parts of Europe was implemented, and this had a terrible effect on the people who were living off the land and who were trying to enforce their customary rights by trying to live off communal land. You don’t need to speak about all the details of British colonialism, but I think this shift that took place, especially in the 1830s with this plantation economy and how it led to some of the issues that Sri Lanka is experiencing today.

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah, I think it should be seen in the context of the colonial experience in most countries around the world, the introduction of an import-export economy into economies and societies that were essentially self-sufficient and were focused on the production of their essential food and other goods and services that they needed. Instead, with colonialism and the development of the super-imposition of the plantation economy and export production, the focus shifted towards these monocultural, large-scale export productions.

In the case of Sri Lanka, first coffee and then tea, and this shifted the priorities. The emphasis was on producing coffee and then tea and then importing food, including rice. This created this dependent model of development for a lot of global, southern countries, and that trajectory has continued because the World Bank, the IMF, and the Western countries are definitely continuing to promote export production at the expense of import substitution, industrialization, which many ex-colonial countries, including Sri Lanka, tried in the immediate post-colonial period. But there are a lot of obstructions from the outside, particularly the Global North, against these countries from becoming self-sufficient and developing their import substitution production, particularly in the areas of food and your needs.

Talia Baroncelli

Would you say that there was a period, and I’m not speaking about pre-colonial periods, but I’m talking about more in the modern experience where Sri Lanka really was able to subsist off the land? Would that have been in the period of its independence and in the subsequent decades, or is that a bit far-fetched?

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah, I think these dependents deepen gradually over time. There were periods when there were efforts to develop local agriculture through the Green Revolution and so on. But that led to a lot of use of agrochemicals and pesticides, and that created other issues. But that also accompanied land commoditization, which was a process that was started under the British.

In order to develop plantation agriculture, they had to introduce private property rights to land so that land became a commodity to some extent mitigated due to social democratic policies that were introduced starting in 1931, which are called the Donoughmore reforms, where there were efforts to preserve the land without being commoditized. Even today, 80% of the land is held by the state with small farmers. They have rights to the land, but they don’t have outright ownership where they can sell the land. But now, there is an effort to release this land to the market. What would happen then is that many of these small farmers who are in dire economic situations would sell the land, and the land would then fall into the hands of external interests, including transnational corporations and agribusiness, for example, for export production.

Part of this whole new colonial project, in addition to getting control over other resources like the ports, energy, and telecommunication industries, is also to get control over the land. In the case of Sri Lanka, it is not just economic control, but because of its strategic location in the Indian Ocean, in the sea route of the east-west maritime trade route, there is a lot of competition on the part of external powers to control the country, and part of that is also control over the land.

Talia Baroncelli

Right. You also speak about the earlier forms of colonialism, of European colonialism in Sri Lanka. For example, the period in which the Portuguese were there, followed by the Dutch. I think it was really the British who had this Crown order saying that all unoccupied and uncultivated land was essentially Crown land, so it would belong to the British Crown. Perhaps you could speak about how this really uprooted certain forms of being, forms of societies which were subsisting in Sri Lanka, and how that destroyed their form of life.

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah. Again, this was something that happened around the world. Prior to the imposition of private property rights, there were hierarchical rights to land. There was a class of overlords who exacted tribute from the farmers. The local people had access to land. The land had value only when it was cultivated. The overlord class actually encouraged people to cultivate the land. But when the British came in and introduced plantation agriculture, they needed a lot of land, and they claimed that the common land, which was open to cultivation by local producers, was Crown land. The common people were asked to produce documentation and titles to land, which didn’t exist because the common land would be cultivated and left as fallow land until subsequent periods of cultivation. There were huge conflicts over land between the British and private interests and the local cultivator class.

I discussed this much more in detail in my first book, Colonialism in Sri Lanka, and the instruments, the legal instruments that were used like what was called the Crown Land Ordinance of 1848, and then subsequently the Wasteland Ordinance of 1897, because the land that was not cultivated was classified as wasteland that belonged to the Crown, which simply was not the conceptualization of land in the pre-colonial period.

In a sense, that project that was started under colonialism still continues with new developments like the so-called MCC and the Millennium Challenge Corporation Act that was introduced to Sri Lanka. Recently, although it was not signed, many of the objectives of that, like land commoditization and opening the land market, are continuing. This could lead to displacement of local people from the land. With the rise of agribusiness and control of land by transnational corporations and some local interests.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, I wanted to ask you about the Donoughmore Commission and the Donoughmore reforms of 1931. They were instituted by Sidney Webb, who was the U.K. Labor Secretary. From what I read in your book, they were able to create a system of universal suffrage where people could vote and also essentially transferred some of the power from the British colonialists to local representatives. It created a local state council if you will. How did this address some of the land issues and issues of people being expropriated from the land and not being able to assert their customary rights to the land?

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah, that’s a good question because you have to see the Donoughmore reforms of 1931 in the context of the Great Depression at the time, which led to the United States, the U.K., and other governments introducing more social democratic policies out of absolute need. A more benevolent form of capitalism was put in place, and some of that had its ramifications in the colonies as well. The Donoughmore commissioners appointed by Sidney Webb had more social democratic leanings.

When they introduced local self-government, along with the franchise, it empowered the majority of the populace, who had no rights to vote or any representation prior to that. With that, with the franchise and universal suffrage, the local elites had to meet some of the needs of people in order to get their vote. That led to the introduction of a system of free education a system of free healthcare, which, in the long term, led to a high quality of life index in Sri Lanka, making Sri Lanka a unique place in the world, especially in South Asia, in terms of standards of living, high literacy, low infant mortality, low maternal mortality. Although the economic growth rate was low in terms of the standard of living, Sri Lanka occupied an enviable position. In fact, I give the statistics in my book had higher PQLI, physical quality of life index, than even China, India, or some of the other Southern Asian countries. These are now being attacked by the expansion of new liberal policies.

One more point with regard to land issues, going back to the Donoughmore reforms. One important piece of legislation that was introduced was the Land Development Ordinance of 1935, which gave access to land to producers but without full ownership rights, not outright ownership, but access to land for cultivation. That empowered the producer class, and again, that is under attack now with the attempt to commoditize land, which would take the land away from their hands.

Talia Baroncelli

Why don’t we speak about rebellion and independence in Sri Lanka? I don’t think the West was so happy with that movement, and neither was the United States. You speak about John Foster Dulles, who was a U.S. Secretary at the time, State Secretary. I think there are some documents that illustrate that the U.S. was potentially looking at overthrowing some of the ruling elite in Sri Lanka because they were opposed to their more communist and nationalist leanings. Why don’t we talk about the influence of the United States in the early years of Sri Lankan independence? In particular, there was an official from the Central Bank who was appointed to run the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

Asoka Bandarage

Right. It’s a very interesting history that is really not part of the mainstream discussion or discourse. I have a whole chapter looking at the transition from the period of classical colonialism to the post-independence period. That was a very vibrant period around the world where the ex-colonial countries were trying to decolonize and move on their own, development parts of their own. For example, African countries are experimented with—African socialism, like Ujamaa in Tanzania. Latin American countries are experimented with import substitution. There was a lot of nationalization, for example, the Suez Canal in Egypt. In Sri Lanka, too, there were a lot of efforts to decolonize and go on an independent trajectory of its own.

With the demise of British imperialism, the United States emerged as the primary dominant political and economic power. From the very beginning of Sri Lanka’s independence, the United States was involved in Sri Lanka both politically and economically. As you pointed out, one was the Central Bank of Ceylon, as it was called then, which was not only first-headed by an American, but he was also the founder of it. He was very much involved in advising the government about internal issues like growing political discontent and went to all the elections, and so forth. Also, there was election interference. The Cold War was happening, and the United States and the West were trying to prevent a lot of ex-colonial countries from joining what they saw as the communist bloc, even when these countries were not necessarily trying to join the communist bloc but they were trying to forge their own parts of development. In Sri Lanka, it was called the [inaudible 00:24:24], which was influenced by Buddhism. It was perceived as a threat to Western dominance. There was also, to some extent, Soviet involvement, but it was much more U.S. and Western involvement.

Talia Baroncelli

The election interference you’re speaking about, I think it was in 1956, and part of it was because of the opposition to an agreement that was reached between; I don’t know if you would still call it Sri Lanka or Ceylon at the time.

Asoka Bandarage

It was Ceylon at the time.

Talia Baroncelli

It was Ceylon at the time. Okay. Between Ceylon and China, Ceylon would sell rice to China below the market price, and then, in return, they would charge a much higher rate for rubber. That was a way in which they could perhaps fund some of their own infrastructure developments. I think a lot of Western countries, especially the United States, saw that as a threat, saw that as Ceylon moving closer towards China, and that would disrupt its own hegemonic rule over Ceylon.

Asoka Bandarage

Right. That was in 1952. The Rubber-Rice Pact was considered one of the best pacts that Sri Lanka had signed, which was advantageous to Sri Lanka. Yes. However, because of western pressure and so on, Sri Lanka did not have diplomatic relations with China until much later.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, why don’t we speak about the 1950s and ’60s leading into the ’70s? My impression is that the party that was in power, the party which gained power in this landside victory in 1956, was not the nationalist, the UNP party supported by the U.S., but was more of a nationalist-socialist, not in the not-sense, of course, but more of having affinity to, I guess, Leninist views or at least to nationalist views of developing the country in a way which would be equitable for all of the people living in the country and to have their workers’ rights and unions. Then, there was a massive shift in 1977 and 1978 in which Sri Lanka came into its own, so to speak, with a new constitution. But that was the period in which neoliberalism was really enshrined in the system. It was baked into the system in the late ’70s.

I think a lot of the debt issues that Sri Lanka currently is experiencing can be tied back to 1978. Why don’t we speak about what happened then, how the political system changed and how this shackling of Sri Lanka to this international economic system in which inequalities were basically exacerbated was really put into place then?

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah, you put it very well. In the ’60s and ’70s, Sri Lanka, along with other ex-colonial countries, really tried to extricate themselves from this colonial pattern of development, which subordinated these countries and where the colonial import-export economy continued. There were valiant efforts not only with regard to creating a new international economic order but also a non-aligned political movement where these countries could develop on their own paths without belonging to either the West or the Communist models, like during the Cold War.

In Sri Lanka, in particular, Sri Lanka played an important role in all these efforts. Although a small country that had very dynamic leaders who were instrumental in the non-aligned movement moving forward, as well as the new international economic order throughout the United Nations Commission on Trade and Development, and also to keep the Indian Ocean as a zone of peace and without Sri Lanka getting enmeshed in superpower struggles. It was a time of hope for both Sri Lanka and the world for these ex-colonial countries to develop their own paths. But it was resisted, particularly by the West. With a certain amount of internal mismanagement, corruption, and all that, some of the programs towards, for example, nationalization of foreign-owned plantations and some import substitution programs face difficulties. Not only because of internal mismanagement and corruption but also because there were a lot of external pressures against them.

With external support, there was this shift to what’s a neoliberal model and a complete, full-scale acceptance of the open economy. As I quoted, the president of the time said, “Let the robber barons come.” It was called the open economy. It was thrown open to anyone, any force that could come and reap profit.

Gradually, the welfare state that had begun under the Donoughmore reforms began to be whittled away, and privatization of the plantations again started and also privatization of the energy and telecommunication industry, and so on and so forth. This has continued from 1977 to date, but with the economic crisis, there’s an intensification of the neoliberal model in concurrence with geopolitical rivalry over Sri Lanka. It’s not just the economic crisis, but it is also the geopolitical rivalry and what has been referred to as a new Cold War that has played into essentially a takeover of Sri Lanka.

If you look at what’s happening now, the ports are owned by three external powers: the Hambantota Port by the Chinese, the Trincomalee Harbor, essentially controlled by the Indians, and then Colombo by India, China, and I think also Japan owns a terminal. Then cell communications and energy corporations are being privatized, including the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, which was created in 1961 when the left-nationalist government nationalized the foreign-owned petroleum corporations at that time, Caltex, Esso, and so on, and created the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, which is now being privatized again.

Talia Baroncelli

What about the private foreign investments that have been conducted in Sri Lanka? Did a lot of them also start around that same time period in the late ’70s? Would you say that a lot of the current financial policy is in a way to secure the rights of these private investors to ensure that there’s stability in the country so that their investments are protected?

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, that prevails over the rights of workers and local people. If you look at the tourism sector, which was one of the major sectors of the export production model, there haven’t been enough studies on that. Who really benefits from tourism?

In many sectors involved in neoliberal export production, a lot of the profits go outside of the country. I have lots of figures on the drain of resources, not just from Sri Lanka, but from the so-called Global South and the net transfer of resources and wealth from the Global South to the Global North rather than the other way around. I think between 2018 and 2017, as I point out in my book, there was a $4 trillion transfer in terms of debt interest alone from the Global South to the Global North. Sri Lanka has been very much enmeshed in this.

What is often forgotten is that a lot of the foreign exchange that the countries earned during the period since 1977 has been from worker remittances. That is ordinary people who are going to work in the Middle East and sending their remittances to the country, which has become the number one form of foreign exchange earnings even during the crisis.

While the elite, including import exporters in Sri Lanka, have, through tax loopholes, stashed their money outside of the country, some $38-50 billion, it is the ordinary workers working in the Middle East, including women, domestic workers, who have been sending money, remittances to the country and also helping maintain their families.

Another sector is the manufacturing sector, the garment export sector, which was promoted with the neoliberal reforms, and Sri Lanka became a big garment exporter. I have a lot of information about that sector. It’s been very tightly controlled. The worker rights have been slashed, and the wages are very low. In each of these sectors, whether it is the continuing plantation sector, the garment sector, the labor export, the tourism sector, the local people, the labor, our rights have been slashed, and their earnings also have gone down with economic downturns like during the COVID crisis, for example.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, we were speaking about the fact that a lot of workers in Sri Lanka have been forced to leave the country to work in other countries and to send remittances back home. One thing you point out in the book is how the same European colonialists who were running the Atlantic slave trade were also importing a labor force into Sri Lanka in, I guess, the 1800s. Hundreds and thousands of people, a Tamil workforce, are being imported. Now, it’s the opposite as to what’s going on right now, where people are forced to leave because they can’t make a living in Sri Lanka.

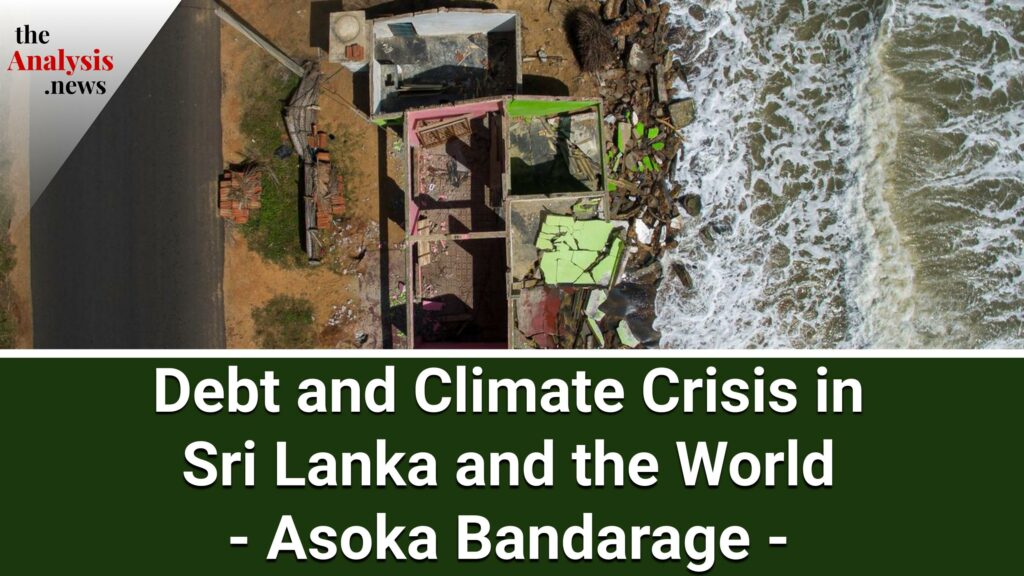

Why don’t we shift now to the issue of climate? Sri Lanka, because of its geographical location and its huge, massive coast, there’s been so much coastal erosion. I think it’s unfortunately very vulnerable to flooding and other environmental catastrophes. Global climate catastrophes, in general, have had a really horrible effect on it. What do you think needs to be done in order to assist Sri Lanka? Should there be reparations? Should there be an institution of loss and damage? This is something that was talked about in some of the recent IPCC climate conventions where loss and damage are an issue. A lot of Global South countries are speaking about this and demanding that money be paid out toward them in the form of reparations so that they could better deal with climate catastrophe since they’re much more vulnerable to a lot of these climate catastrophes.

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah. We cannot separate the environmental issue from the issue of protecting people and societies. We have to have both the ecological and social welfare approaches that are simultaneously addressed. Some of the discussions around debt-for-nature swaps for the Global South need to be really examined much more closely. A country that is debt-ridden, like Sri Lanka, could be asked to protect its forests in a debt-for-nature swap. On the face of it, it’s well and good. We have to remember that people’s livelihoods are important. The onus of protecting the forests and the environment should not be placed on the Global South alone when, in fact, countries like Sri Lanka have had a minuscule carbon footprint. Their carbon emissions have been minuscule compared to the emissions of the dominant countries, the Global North, the U.S., Europe, China, and so on. I think we have to have more of a climate justice approach where the climate issue and the survival of people are addressed together.

Talia Baroncelli

Sorry to interrupt you, but what is the debt-for-nature swap that you’re speaking about? Could you explain what that is, as well as some of the mechanisms tied to it?

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah. I don’t know too much about it, but that’s being talked about. In order to address the global climate issue, one approach could be that the debt of some of the global southern countries be cancelled if they agreed to protect natural resources, particularly forests. On the face of it, it’s a good idea, but some local people themselves, not just in Sri Lanka but around the world, have been questioning that: should that be at the expense of the survival of local people who depend on forest resources and to some extent forest development. That’s why it has to be a much more balanced approach.

I’m not saying that forest protection is not important. It’s extremely important in a place like Sri Lanka, where deforestation has been immense starting in the colonial period, mostly starting with plantation development. But at the same time, there’s also population pressure and the need for resources for people’s livelihood. I think it has to be a more balanced approach. It’s not an approach that is anti-technology or anti-development but a more balanced approach.

There are many organizations and networks that are talking about localization and not just export production, but putting said, sufficiently and local economic autonomy and survival of the planet and people’s livelihoods before profit making, which continues to be the dominant criterion despite the environmental destruction and massive social destruction that is going on.

Talia Baroncelli

How would you assess the environmentalist movement within Sri Lanka itself? There were protests, for example, in 2022 against the prime minister at the time. But would you say that they were really influenced by this ecological consciousness that climate change is something that’s a huge issue in Sri Lanka and the world and the rest of the Global South? This awareness of neoliberalism and how it’s exacerbating the debt issues in Sri Lanka, or was that not part of the [inaudible 00:41:56]?

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah, I think not enough. There have been environmental organizations and networks fighting a number of these neoliberal and externally funded projects, including the Chinese port city, the Hambantota city, the Millennium Challenge Corporation Compact, and so on and so forth.

If you look at the Aragalaya, a protest movement that emerged in response to the massive economic crisis and the ouster of the previous Rajapaksa regime, they called for a system change, but for them, the system change was the removal of the then-president and the prime minister, rather than an understanding or a deeper exploration of the roots of the crisis in the global economic and financial system. Also, there was really a lack of understanding of the environmental dimensions of the issue.

I think both in Sri Lanka and the world, we have to put the environment first and the people as part of the environment before profit and the whole domination paradigm, if you will, which is what is being pursued in spite of this ecological and social collapse that is going on in Sri Lanka and the world, and essentially this takeover of a country which had a very high quality of life and now becoming a really impoverished country. In a country which had a fine education and a free healthcare system, now, some of the hospitals don’t even have a single anesthesiologist because the doctors are leaving. Professional classes are leaving. It is a real tragedy to see this country, which was an exemplary country in terms of the standards of living in the Global South, becoming an indebted, impoverished country, and people are in such a desperate situation that there is not much voicing of alternative perspectives. That’s why I think talking about Sri Lanka in the global context and in the international arena is really important to bring these issues before the global audience.

Talia Baroncelli

How would you assess Sri Lanka’s role geopolitically? It’s been neutral for many decades, but would you say that it’s in with the BRICS, so to speak, that it’s maybe seeing its future together with countries like Brazil, India, China, and Russia since the Bretton Woods system has only really continued its impoverishment?

Asoka Bandarage

Yeah, many presidents in Sri Lanka even recently have declared a neutral policy for Sri Lanka. But because of the intense geopolitical rivalry over Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka has become subordinate to several masters instead of one. There’s so much pressure. Instead of using this strategic position to its advantage to get what is needed for the country and its people, it’s become dependent and servile in meeting the interests of several foreign powers, for example, China, the United States and the West, and India, which is an increasingly dominant player in the Sri Lankan case.

Again, this is not a new situation. As I pointed out, Sri Lanka has had the longest history of European colonialism in Asia, starting in 1505. There have been battles over the Trincomalee Harbor among various foreign powers. The strategic location and the natural resources of the country, without benefiting the people, have also brought a lot of external interventions which are not necessarily good for the country. Of course, a local collaborative class has been implicated in this as well. Because without local collaboration, neither classical colonialism nor the neocolonialism of today could continue.

Talia Baroncelli

One last very, very short question before you go. I think it’s maybe nice to end on a positive note. Your book speaks about ecological alternatives. Perhaps you could sum up what you meant by partnership. You’ve alluded to this throughout the conversation, but you speak about partnership as being a way forward of ensuring that there’s respect for the land, respect for people’s rights, and respect for workers. Perhaps you could speak about that concept of partnership and how that may provide a way out of the debt and climate crisis for Sri Lanka.

Asoka Bandarage

Right. A lot of the language of partnership, democracy, and human rights has been appropriated and misused. Partnership, ultimately, is about partnership with nature and having a different consciousness. I talk about the transformation of consciousness because the dominant economic model, even the model that seems to be pursued by the BRICS countries, although they are presented as an alternative, is one pursuing the same goals of domination, profit, and power.

I think instead of that; we need one where we honor the needs for social justice and environmental sustainability, which requires us to live with nature. Instead of an approach of domination over nature, how we develop ways of living in harmony with nature. I think there’s a lot of research and networks working towards that. For example, localization efforts, where bioregionalism and agro-ecology are developed over agro-business and export agriculture. The transition movement talks about renewable sources of energy and organic agriculture instead of chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

There are efforts in Sri Lanka as well, but I think it has to be part of a global effort because Sri Lanka is not an isolated island. It’s very much a part of the global economic and political system and ecosystem. I think there’s got to be more consciousness. The crisis in Sri Lanka, Zambia, or some other indebted country is not just an isolated one, which is how it is approached. Rather, see this as part of a systemic problem and that we need systemic change, which means really questioning the dominant model driven by profit and domination towards something that upholds harmony and interdependence, which means, ultimately, people and social movements working together to bring that transformation, consciousness, and putting that into policy.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, I think you get an excellent point by saying that the approach of BRICS is not really an alternative because it essentially pursues the same capitalist profit-making. That’s not something that can help the world get out of the current climate catastrophe in which it faces itself. A real alternative would be something which is inherently anti-capitalist and which is distributive and also respectful of the world and the climate and people which inhabit this planet.

Dr. Bandarage, it was really great speaking with you today. Thank you for taking the time, and I highly recommend your book, Crisis in Sri Lanka and the World, to anyone interested in the legacy of colonialism and how these issues continue to impact countries in the Global South struggling with debt. I hope to have you on again in the future.

Thank you for watching theAnalysis.news. If you enjoyed this content, please consider donating to the show by going to theAnalysis.news and hitting the red button at the top right corner of the screen; get onto our mailing list, and subscribe to the podcast on whichever platform you watch the show. You can also go to our YouTube channel, theAnalysis-news, and like and subscribe to the channel. Thank you so much again, Dr. Bandarage; it was great to have you.

Asoka Bandarage

Thank you very much. I really appreciate it. Thank you, Talia.

[powerpress]

[simpay id=”15123″]

“Asoka Bandarage has taught at Yale, Brandeis, Mount Holyoke, Georgetown, American and other universities and colleges in the U.S. and abroad. Her research interests include social philosophy and consciousness, environmental sustainability, human well-being and health, global political economy, ethnicity, gender, population, social movements and South Asia.”