This interview was originally published on October 14, 2014. Dr. Kumar says after 9/11, with the ratcheting up of anti-Muslim racism, she decided she had to do something about it.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay.

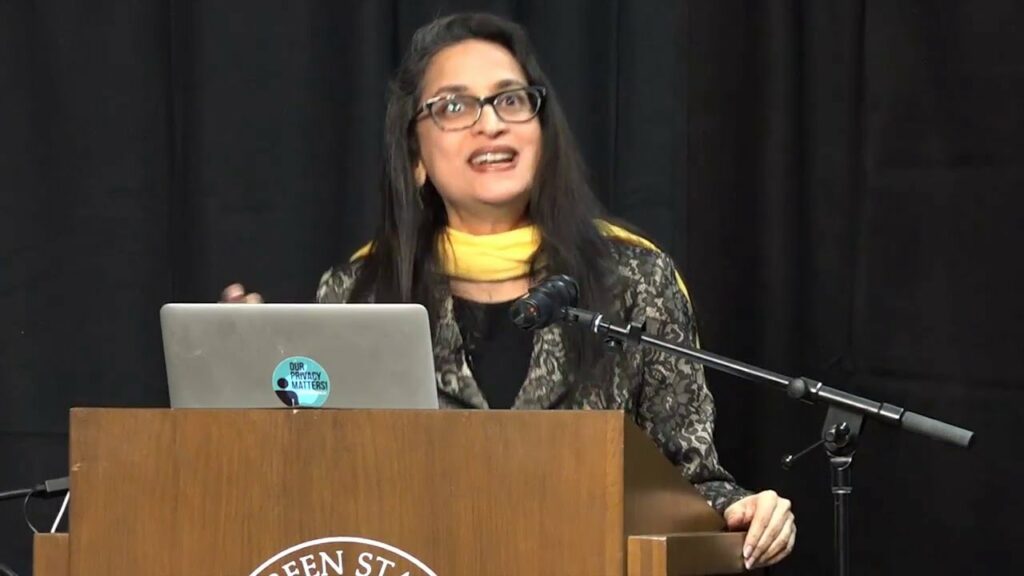

We’re continuing our series of discussions with Deepa Kumar. And she now joins us in the studio.

Thanks for joining us.

DEEPA KUMAR, ASSOC. PROF. MEDIA STUDIES AND MIDEAST STUDIES, RUTGERS UNIV.: My pleasure.

JAY: And just to remind everybody, Deepa teaches. She’s an associate professor of media studies at Rutgers University. She’s–also serves as an officer in the teachers union. Her books include Outside the Box: Corporate Media, Globalization, and the UPS Strike, and her latest is Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire, and she’s writing Constructing the Terrorist Threat: The Cultural Politics of the National Security State.

So, normally we start with a personal back story, but this time we didn’t. So now we will.

KUMAR: Okay.

JAY: Alright. So you’re born in India. What are the politics of your household? When you start to become aware of the world around you, what kind conversations are you hearing?

KUMAR: Well, my extended family was involved in the national liberation struggle against the British. And so, if you go to the house that I grew up in, where my parents and grandma still live, the very first room you enter, there’s this gigantic picture, a framed picture of the Constituent Assembly of India. And it’s up there because my great-grandfather was part of the Constituent Assembly, helped to write the Indian Constitution. So I grew up from, you know, as long as I remember, being conscious that British colonialism is bad and that we did the right thing in kicking them out and establishing an independent India. And my grandmother used regale me on stories of how her brother was once being pursued by the British and he walked for 100 kilometers to the farm that they were staying at, and she had to hide him in a grain silo, pour grains over him, and the British came and they couldn’t find him. So I guess empire and colony has always been a part of my consciousness.

JAY: Now, there are a lot of different political trends as part of the movement against British colonialism. Which one were your family?

KUMAR: The Congress. So my granduncle was the first chief minister (the equivalent of a governor) of the state that I grew up in, and he was a Congress–.

JAY: Which was?

KUMAR: Karnataka. And, of course, at the time, the Congress Party was a lot more idealistic and you had Nehruvian socialism. And, you know, of course, that’s not really what I would consider socialism, but it was certainly egalitarian. It was about looking out for the poor and all the rest of it. And so there are family portraits with Nehru and other people.

JAY: Now, your current views on things are somewhat to the left of what Congress certainly is now, but probably even then. What are some of the formative moments for you?

KUMAR: I think my key activism was around women’s rights. To me it was just always so contradictory to hear the patriarchal stories of what was expected of me is to grow up and marry a rich guy and produce a bunch of babies. And here I was, growing up, and Indira Gandhi was prime minister, and my aunts were–some of them were incredibly strong women, running their own schools and so on. And I just thought, this story doesn’t make sense for me. And so I organized for women’s rights and I ran for women’s secretary in my college days, arguing around feminist issues.

JAY: Now, when you start to become more politically aware, this is sort of, like, mid ’70s, early mid ’70s?

KUMAR: I would say ’80s?

JAY: Eighties.

KUMAR: Yes.

JAY: So Vietnam War is over.

KUMAR: Yes.

JAY: What are some of the big issues? I mean, the ’80s are pretty tumultuous in India.

KUMAR: They are, but I’ll be honest with you that I wasn’t political in the formal sense. That is, by that point, there had been so many disappointments in the form of Indira Gandhi, you know, calling for the emergency, the forced sterilization program, and therefore politics as such had become so corrupt, that it didn’t occur to me to think in those terms. And so I was much more focused on what I can do around me.

And the other thing that I gravitated towards is questions of inequality. I grew up in a middle-class home, but every day on the way to school I–.

JAY: What did your parents do?

KUMAR: My father is an engineer. My mother is a schoolteacher. But they moved to the land for a little while and tried to till the land and so on. But every day on the way to school I’d see this huge shantytown. And it just always bothered me that some of us could have access to education and possibly come to the United States, and others would just never go beyond their station.

But I never quite understood that to be a structural, systemic problem. And so I had aunts who did sort of educational work, charitable work, and so forth. And so it was not until I read Latin American theorists, people like Andre Gunder Frank and the Egyptian Samir Amin, and later Marx, that I realized that capitalism is fundamentally a system based on inequality.

JAY: So do you read any Marx before you get to–you come to the United States in ’92 to go to school. Did–that part of your process is here?

KUMAR: Yes, that part of the process is here. I took a course in development communication, where we read basically about the development of underdevelopment and how modernization is essentially a pro-capitalist framework which has nothing to do with uplifting the majority of people.

JAY: So when you go to school here, you get here in ’92. Where did you expect you would be now? And, I mean, were you planning an academic track? Are you surprised at where you are politically now compared to where you were in ’92?

KUMAR: Well, since I was always–I had a tendency to side with the oppressed and the exploited, in a way, if I hadn’t discovered the frameworks to make sense of it, I would have had to create it, I think, sometimes. And I’m really thankful that I took courses from so many progressive liberal and radical professors, who opened me up to books that helped me be where I am today and all of the various activists who I learned tremendously from.

JAY: So you didn’t have to do–or I should ask: did you have to do much unlearning in terms of your worldview?

KUMAR: Some of it, certainly. I had to do some unlearning around the role of India in the region, the idea that India is actually a sub-imperialist power when it comes to its relationship to–.

JAY: So, yeah, you get over some of your nationalism.

KUMAR: Exactly, get over some of the nationalism, become an internationalist. And I think the experience of travel sometimes does that, doesn’t it? Because it removes you out of your comfort zone and it makes you think critically not just about your home country but anywhere you go. And that’s a useful consciousness to have, which I’m sure you share as well.

JAY: When do you start to focus on media?

KUMAR: So I was planning to be a filmmaker. That was what my first master’s was in, and that’s what I set out to study. And I realized I wasn’t very good at it, and I was better at theory and I was better at understanding and explaining the world. So I decided to do a PhD. And then I suppose I just never left the university. I completed the PhD, got my first job, my second job, and I don’t intend to leave.

JAY: Well, let’s get a little bit into the some of your work. The book Outside the Box: Corporate Media, Globalization, and the UPS Strike, what led you to that? And what was your discovery in doing that?

KUMAR: I was in Pittsburgh at the time, and I was doing solidarity work with steelworkers who–you know, the story of steel in Pittsburgh is of course well known. And the few steel mills that remained were in the process of being attacked. And so a bunch of us, students from the University of Pittsburgh, would drive to these towns and actually support the strikes and try to create solidarity between various unions and so on.

And then the UPS strike is–well, we didn’t expect a strike, but we certainly knew that there was a contract campaign on and that Ron Carey had actually shaken up the Teamsters. And so some of us would go and stand outside UPS hubs handing out literature that was produced by the Teamsters and so forth.

And I figured, you know, I was watching media coverage of the strike, and it was so startling to me that in the second week of the strike, you actually start to see prolabor coverage. And that was the product of huge public support, two to one in support of the Teamsters and workers. And that’s because the Teamsters basically made this a story of our struggle is your struggle. This is about corporate America, you know, sort of messing with all of us. And I thought I should tell the story of that as how to win people to a prolabor perspective and to have a working-class consciousness.

JAY: So when do you start to focus on the issue of Islamophobia in the media?

KUMAR: That’s 9/11.

JAY: Now, let me just ask, first of all, your background is not–is your background Muslim or no?

KUMAR: No.

JAY: It’s not.

KUMAR: My parents are Hindu. I became nonreligious a very, very long time ago.

JAY: And in your household or in any of your circles, I mean, you can find Hindu households in India that are as Islamophobic as anybody in the United States and then some.

KUMAR: Oh, yes.

JAY: And then some.

KUMAR: I mean, it startles me. So I’ve been here since 1992, and every time I go back, I’m just startled by how people who I knew who had a secular mindset have become more and more Islamophobic. And that has everything to do with the BJP and the ways in which they ratcheted up Islamophobia.

JAY: And for everyone that hasn’t followed it, BJP has now got the prime minister of India,–

KUMAR: Yes.

JAY: –Modi.

KUMAR: Yes.

JAY: How do you just–while we’re there, I mean, how do you explain this, how you could–. I mean, I remember–I mean, I don’t follow Indian politics that closely, but this idea of being against this kind of communal warfare and fighting, it was kind of unimaginable that at this point in history you could elect a BJP prime minister.

KUMAR: Right. Well–.

JAY: Certainly with such numbers.

KUMAR: Right. I mean, I don’t know if you can look at this election in isolation from the advances that they’ve been making since the ’90s, right? There has been a decidedly communalized atmosphere in India ever since 1992, which is when they took out that famous /strɑtiˈɑtrə/ to demolish this mosque supposedly built on top of a Ram temple and so on. And that’s just one part of the story.

The other part of the story is the crisis of secular nationalism in India, the fact that the Congress Party just failed to deliver on all of its promises, which creates the opening for people like the BJP, who are the political wing of the RSS, the RSS being–.

JAY: But you would have thought in theory you could have created an opening for the left. But the BJP is so associated with Islamophobia that you wouldn’t think that would be the natural alternative.

KUMAR: Well, I would place it in the context of how fundamentalists have seen an opening since the 1970s everywhere, whether it’s in the U.S. and the Reagan victory on the backs of the new right or in Israel and the fundamentalists there and so on. It’s–in all of these cases, you know, it’s a question of left and progressive values just failing to deliver and creates the opening for these far-right people.

And I think the point you make is very important, which is the far left unfortunately didn’t have an alternative in country after country, because Stalinism and the influence on communist parties meant that they just tailed the secular nationalists, right? They just said, we are no different from the secular nationalists, so that when secular nationalism goes into crisis, so does the credibility of the far left. And so instead you see the right, because people want to throw the old bums out and want a different alternative. And that’s the current context as well. People think that Modi is going to revive the Indian economy and make it all wonderful, India shining and so forth.

JAY: It’s still surprising to me. I mean, I don’t know the situation well enough, but you don’t have anything, it seems, of any scale in India that would be something like what’s going on in Latin America as an option.

KUMAR: Yeah.

JAY: And why?

KUMAR: Yeah, that’s a really good question. I can’t say I’ve fully thought that through. I stopped studying India a while back and focused more on the Middle East and North Africa [crosstalk]

JAY: Alright. Well, let’s get back to this, then. So in terms of you working on the issue of Islamophobia, I mean, you’ve got roots of this in India because it was such a big issue. I mean, the battles and the killings and such were at some very serious scale many times. But when does this start to become a focus of your work here?

KUMAR: So 9/11 happens and you start to see the ratcheting up of anti-Muslim racism. And I say “ratcheting up” because that’s not the origin of Islamophobia. It has a much longer history. And to me that was just startling, to see the stereotypes that pass as knowledge, as credible knowledge in this country. And having grown up literally with Muslims everywhere, when–my family home we had Muslim neighbors on both sides, and we celebrated all of our religious festivals together, and one of my best friends was Muslim, and so on. And India has 100 million Muslims. And so, viscerally I responded to the kind of demonization that was going on, and I thought, you know what? I should do something about it.

And then, sure enough, I was teaching at that time in North Carolina, and a young Lebanese student, I believe, was beaten up because, of course, the rage turns into this kind of, you know, hate crimes and so forth at a local college. And people, the administration, the cops just looked to the other side. They didn’t do anything about it. And so Amnesty International organized a panel called “Islam Is Not the Enemy” and they invited me to come speak on it. And that was really the first sort of moment at which I thought, alright, I have to educate myself on the history of the relationship between the East and the West, but more importantly, know enough so that I can bring arguments into the antiwar movement, so as to push back against this form of racism, which fundamentally was the handmaiden of empire.

JAY: Okay. In the next segment of our interview, we’re going to get into the history of Islamophobia. So please join us on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network with Deepa Kumar.

[simpay id=”15123″]

“Deepa Kumar is an Indian American scholar and activist. She is a professor of Journalism and Media Studies at Rutgers University.”