On Reality Asserts Itself with Paul Jay, Phyllis Bennis examines the Israeli debate about Iran and Palestine, and the complex changes taking place in Middle East politics. This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced December 11, 2013, with Paul Jay.

No posts

TRANSCRIPT

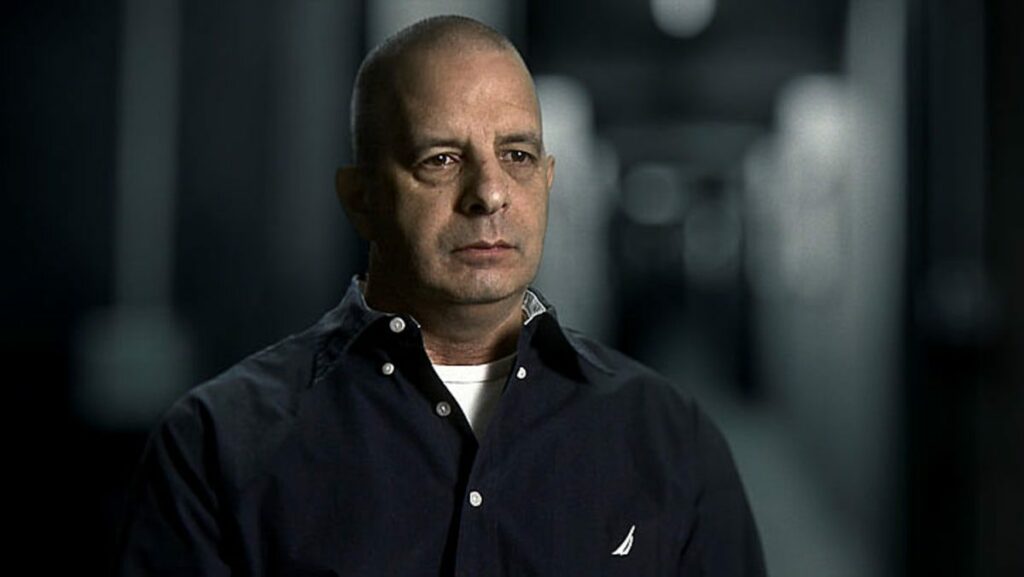

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network, and welcome to Reality Asserts Itself. I’m Paul Jay.

We’re continuing our series of interviews with Phyllis Bennis. We’re going to dig into some of the more current issues now, starting with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Phyllis is the director of the New Internationalism Project at the Institute for Policy Studies. She’s been a writer, analyst, and activist on Middle East and UN issues for many years.

And I did a much lengthier introduction in part one. And I suggest you do watch part one before you watch this part two.

But let me just quickly tell you some of the books Phyllis has written: first of all, four primers–a primer on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, one on ending the Iraq War, U.S.-Iraqi crisis, and U.S. War in Afghanistan; and many other books, including–let me pick one–Challenging Empire: How People, Governments, and the UN Defy U.S. Power.

Thanks for joining us again, Phyllis.

PHYLLIS BENNIS, FELLOW, INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES: Great to be with you.

JAY: So I want to start off talking about some of the debate that goes on in Israel–or perhaps lack thereof.

Haaretz has a piece today, and I’ll read a quote from it. The headline is “Ex-Shin Bet Chief: Effects of Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Riskier Than Nuclear Iran”. The story goes, former Shin Bet chief Yuval Diskin said Wednesday evening that he believes the unresolved conflict with the Palestinians has much graver ramifications for Israel’s future than the Iranian nuclear program. Quote, “I say it even though it is unpopular to do so.” “We need an agreement now, before we get to a point of no return, after which a two-state solution will be impossible.” Speaking at an event commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Geneva initiative, Diskin said, “I would like to know that our home here has clear borders, and that we’re putting the sanctity of people before the sanctity of land. I want a homeland that does not require the occupation of another people in order to maintain itself.”

The people I talk to in Israel, including our journalist, says, like, this is a voice that barely exists in Israel, that there really isn’t much debate about this. And Diskin and people like him are kind of off in the wilderness.

BENNIS: You know, I’m not sure I absolutely agree with that. I think that there is actually–in the press, at least, there is more debate in Israel and in the Israeli press than there is in the United States, where there’s much more fear about challenging anything about the general accepted discourse on Israel. Inside Israel, Diskin is one of a number of people. There was a film that came out last year called The Gatekeepers that featured a number of former Shin Bet leaders like him.

JAY: Just for those that might not know, Shin Bet is the Israeli intelligence service. And in fact, as Phyllis is saying, many former heads of the various intelligence services in Israel have said similar things to this.

BENNIS: So that’s not new. It’s also, I think, understood in a lot of parts of Israel that the situation with the Palestinians is not going to work the way it is now.

Now, the problem is that for most Israelis, the situation is very comfortable. Israelis have passports. They can go anywhere. Israel is the 23rd per capita wealthiest country in the world. It has the fourth-largest/strongest military in the world. It has the only nuclear arsenal in the Middle East. Iran doesn’t. Israel does. And it has, of course, the uncritical backing of the United States. So things for Israelis are pretty good.

You know, the number of Israelis killed in violent attacks is way down. There were two this year, zero last year. I mean, it’s–this they can deal with. This is not a problem.

The problem is, for the Palestinians, the idea of a two-state solution, if it hasn’t already disappeared, is virtually about to disappear. And I think that in Israel a lot more people would be aware of it and are starting to become aware of it again in a way that they used to be more aware of it because of the global campaign known as boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS), which is a campaign to use nonviolent techniques of both economic and other kinds of sanctions to pressure Israel to stop its violations of international law against the Palestinians.

In the main, so far, ordinary Israelis have not felt that, but you are starting to see the impact of those kinds of campaigns on ordinary Israelis. And if you look at the model in South Africa in the anti-apartheid period, it was when the sports boycott took hold that ordinary South Africans, who are absolutely sports-driven, sports-crazed, that’s when it started to connect that this really wasn’t going to work in the long-term. In Israel, it’s about science and culture and technology that’s are–that’s that obsession at a society-wide level. And when you have things like–just in last couple of days, we saw the American Studies Association, one of the most prestigious academic organizations in the United States, just voted to support the academic boycott against Israel. That’s going to have an enormous impact on Israeli academics. When leading theater and musicians, theater people and musicians decide to abide by the boycott call and refuse to perform in Israel, that cultural impact is having a huge effect.

JAY: Now, this quote I read from the former Shin Bet leader–and as you said, he’s not the only one. There’s been a lot of these former guys. But the American media almost entirely ignores these guys. And it’s like you’re–this is, like, almost–this is an important section of official Israeli public opinion.

BENNIS: It is, but I also think that things have changed. I don’t think that’s the case anymore. If it were, you would not have seen the film The Gatekeepers nominated for an Academy Award for the best documentary. It got enormous publicity. It was reviewed in every major paper and, you know, on NPR, and all the TV stations were talking about it. Now, does it get talked about all the time as much as it needs to? No.

JAY: Well, how much influence is this having in the American Jewish community? And why don’t we see any reflection of this in American politics? Netanyahu comes to Congress and gets–like, you know, what is it? Fifty standing ovations.

BENNIS: This is the big challenge. We have massively changed the discourse in this country. The press is different. Publishing is different. Popular culture is different. And the debate in the Jewish community is different.

What has not changed is the policy, and that has far more to do–.

JAY: The policy and the politics, like, congressional politics.

BENNIS: Yes, but that’s where the policy gets made. That hasn’t changed. And that’s the huge challenge that we face.

If we look at an organization like the U.S. campaign to end the Israeli occupation, it’s 12 years old. When we started, it had, I think, six organizations and about 15 people meeting–very nervous, and they were scared about what we were about to do. Now there are over 400 member organizations that include giant church-based organizations, Jewish Voice for Peace, which has 140,000 members. You know. All of these giant organizations are part of that coalition, of that campaign.

So we see a huge shift in how people are talking about this issue, what is safe to talk about now. You know, I don’t worry about getting shot by the JDL the way I used to anymore. It hasn’t happened for years. You know, the debate is entirely different.

What’s not different is that our political system is still hijacked by corporate interests, by wealthy lobbies. One of the most powerful of those lobbies, of course, is the set of pro-Israel lobbies led by AIPAC, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee. There’s a host of others, Christian Zionist organizations, as well as all the Jewish organizations.

JAY: We did some stories and some investigation on this, and the conclusion we came to: that a great deal of North American Jewish public opinion is extremely critical and does not vote based on Israel issues. But a lot of big Jewish money is very closely connected to Netanyahu and Likud.

BENNIS: Right. This is–and it’s not surprising. The money follows the right. You know, it’s not surprising that the right wing is always better funded than the left, because the right wing represents the interests of big money, whether it’s corporations, whether it’s the military-industrial complex, or in this case it’s the wealthiest component in the Jewish community and among Christian Zionists. That’s where the money is.

It used to be that AIPAC, the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, the other pro-Israel lobbies in the Jewish community, could meet with members of Congress and say, look, we’ve got money. We may give you some. Mostly we’re going to hold you hostage, that if you don’t toe the line, we’re going to fund an opponent that you don’t even expect yet. But we’ll also bring you votes, because we have influence in the Jewish community and people will vote the way we tell them. They can’t say that anymore. And that’s huge. They still have the money, but they don’t have the votes, because the Jewish community has changed.

JAY: Something happened on Syria that was rather–seemed unique, this moment where AIPAC seemed to be lobbying heavily for an American military intervention.

BENNIS: And they lost.

JAY: And they lost.

BENNIS: That’s not the first time it’s happened. We saw it back in 1981, where AIPAC was dead set against, as the Israeli government was dead set against, allowing U.S. arms sales of what were known as AWACS (it was a particular kind of high-tech surveillance plane) to Saudi Arabia. And the Israelis at that time, unlike now, where they’re actually quite close to being in bed with the Saudis, at that time there was a great deal of antagonism between Israel and Saudi Arabia, and the Israelis and their lobbies said, this is unacceptable; we cannot allow the U.S. to sell AWACS to Saudi Arabia. At that moment, because there was a divide between the interests of the pro-Israel lobbies and what was perceived as U.S. national interests, the national interests won.

The reason that the lobby often seems so powerful is that, yes, it does have a lot of influence. I don’t–I’m not denying that. But it has been historically pushing in the same direction as the majority of U.S. policymakers want to go. So imagine if you’re running behind a car, and you start to push the car as it goes forward, and the car starts to go fast. You can claim, wow, I was really strong–I pushed that car 30 miles an hour. You know, maybe you didn’t. Maybe you were pushing it in the direction it wanted to go anyway.

Now, it is true that the lobby has had enormous influence.

JAY: Yeah, ’cause a lot of the American–there is a section of the American professional foreign-policy establishment that doesn’t agree with this totally pro-Israel status.

BENNIS: Right. The realist sector often is very critical of the tight bond between the U.S. and Israel that prevents a more strategic assessment of where U.S. interests actually lie. I often disagree with them, because they see their–U.S. interests are with oil-rich monarchies instead of Israel, etc. There’s a lot of social questions to that. But they are historically significant in the U.S. policy debates.

JAY: So, now, President Obama is developing these negotiations with Iran. Clearly Netanyahu and that whole section of the Israeli elite are opposed to this. There’s a whole section of the American neocons are opposed to this. The Saudis are opposed to this. But is this a kind of a–something new in American politics that an American president would so get off the agenda of Israel? And he has not, up until now, certainly.

BENNIS: This president is not off the agenda of Israel. We should be clear about that.

JAY: On Iran?

BENNIS: This president–let me say it–this president has been, according to Israeli officials, the most pro-Israeli president in the history of the United States.

JAY: Vis-à-vis the Palestinians.

BENNIS: I said the most pro-Israeli politician, the most pro-Israeli president. That includes arms sales. It includes collaboration on new weapons systems. It includes billions of dollars in military aid every year. It includes protecting Israel at the United Nations to ensure that it’s never held accountable.

Having said all that, it is also this president, Barack Obama, who has been willing to cut a deal with Iran as part of a global movement of countries, of governments that are looking at changes in the region as a whole and saying, I know the Israelis don’t like this; I’m going to do it anyway.

So both of those things are true. The fact that Obama has signed off on the deal with Iran does not change the fact that he is still the most pro-Israel president overall that we have had in the United States.

Now, at the political level, is Bibi Netanyahu going to, you know, welcome him as a brother and a friend? No, absolutely not. The tension between Obama and Netanyahu remains very, very tight, and it’s very strong both on the question of Palestine, in terms of language, and strategically on the question of Iran.

Right now, Netanyahu is quite isolated in Israel. The military and the intelligence officials in Israel are saying that there needs to be an agreement with Iran, that going to war with Iran would be crazy. The current chief of staff of the IDF, the Israeli Defense Force, has said, we could do it alone, we could go to war alone. But both he and other top military and intelligence officials have said, but it would be crazy for us to do it, because if we did, while we might have the military capacity, we would be left with the entire world turning against us and we would lose the support of the United States and Europe and the rest of the world. That’s a very true assessment, that it’s a huge risk.

JAY: And that’s partly because Obama is saying–and I think he is listening to American foreign-policy professionals in saying–and, you know, his Asian pivot, his whole strategy is about China–that getting involved in a war with Iran would weaken the ability of America to project its power, which is the same reason he opposed the war in Iraq, not ’cause he’s antiwar and not because he’s pro-peace with everybody. He wants to maintain this ability to project power. So a deal with Iran makes sense. But the Saudis hate it, the Israelis hate it, and he’s willing, apparently, to do it anyway.

BENNIS: Right. And I think that that is a very important statement about how he sees U.S. foreign policy.

It’s also true that this is a moment when conditions in the Middle East are shifting massively and nobody is very sure how things are going to play out. So the Saudi opposition is–not because Saudi Arabia wants to go to war with Iran, but Saudi Arabia and Iran are contending as to which is going to be the regional hegemon, who’s going to be more influential.

JAY: Well, the sources I talk to that are very connected to the Saudi military establishment, they have told me they don’t want to go to war with Iran, they want the United States to go to war with Iran, and that they do want an actual hot war. People I’ve talked to–.

BENNIS: I think some in Saudi Arabia do want to. I don’t think that’s the majority opinion in the royal family, and it certainly isn’t the opinion of most Saudis. And I think that that’s important, because right now the Saudi royal family has less support domestically than they’ve ever had since the kingdom was created. They’re looking across the border at Bahrain, where only the intervention of 15,000 Saudi soldiers prevented the overthrow of the king of Bahrain. They’re looking at the UAE, at Jordan. In all these absolute monarchies–Jordan somewhat less, but even there–where there is beginning to be real ripples of change, the Arab Spring is not leaving out the monarchies, despite the very different political relations.

So no one is very sure how this is going to play out. The decision that the Obama administration had made–late, but they made it–in the period when the U.S.-backed dictator of Egypt, Hosni Mubarak, was being overthrown in early 2011, in that period you saw a decision by the administration that we can’t keep up this position that we can only deal with military dictatorships and absolute monarchs; we’re going to have to deal with some of these Islamic-flavored movements and governments. So they were willing to do that. Then that got smashed with the military coup that overthrew the government of Mohamed Morsi.

JAY: Which the Saudis had a lot to do with.

BENNIS: Which the Saudis had a lot to do with. And the Saudis now are making up massively for the loss of U.S. influence in Egypt by bringing in a coordinated gift, if you will, of $12 billion, dwarfing the $1.3 billion that the U.S. was paying to the Egyptian military. The Saudis, along with the U.A.E. and some of the other Gulf states, have kicked in $12 billion to the government and the military with the overthrow of the Muslim Brotherhood.

So you have this very complicated issue where Iran is now seen as having a lot of influence in the region through Hezbollah in Lebanon, through the government in Iraq–despite the fact that the government is dependent on U.S. funding, it’s politically far more accountable to Iran than it is to the United States, and, of course, in Syria, where you have a real regional war, a proxy war being fought out in Syria. There are at least six wars being fought today in Syria. And the people paying the biggest prize, of course, are the people of Syria.

JAY: There’s an interesting report today in AP which talks about Iran saying, once the sanctions are dropped–and they’re talking as if they’re assuming this six-month deal will become a real permanent deal–Iran is going to start pumping oil without any containment. They don’t care what OPEC has to say about how much oil, and they don’t care. I think the quote was, we don’t care if the price of oil goes down to $20.

BENNIS: Twenty dollars a barrel.

JAY: Well, if there’s anything’s that’s going to freak the Saudis out, it’s that.

BENNIS: That’s certainly true. And the Saudis are facing a huge challenge of their oil is not going to last forever either, and only in the last few years have they been willing to acknowledge that. The kingdom is facing a serious challenge with a growing population, and enormous, bloated royal family whose levels of privilege are legion.

JAY: And losing leverage with the United States, the way the United States is becoming such a big oil and gas energy producer now. I saw something that said in four or five years the United States could be the number one energy producer in the world.

BENNIS: Right. A lot of that is because of national natural gas, but also it’s because the U.S. government is willing to take on fracking and do all of these really dangerous kinds of unusual, if you will, sources.

JAY: But all of this, again,–

BENNIS: But the other side of it–.

JAY: –lowers the leverage of the Saudis.

BENNIS: Right. But the other thing that lowers the leverage is that as of 2010–this is now three, almost four years ago–the Middle East has not been the source of the largest amount of imported oil. Even as imports in general have gone down, the Middle East has been eclipsed by Africa for who is providing the majority of imported oil to the United States. So, you know, we’re looking at a situation where the oil weapon no longer exists in the same way.

So everything right now in the region is shifting. And in that context, it makes it much easier, I think, for the Obama administration to move towards an agreement with Iran, which, given that it’s quite–it’s narrow, it’s limited, it’s only going to be six months, there’s huge opposition brewing both in Congress, in Israel, from Saudi–.

JAY: But it’s a seismic shift from U.S. policy, Israeli policy. And in reality, Saudi policy had been regime change in Iran. They’re a long way from regime change.

BENNIS: This is a long way from regime change. There’s a kind–and I think that the war in Syria and the sense of what the cost would be–but more than anything else–and I think this is true for the Obama administration–. I don’t entirely agree with you about your assessment of where Obama was on the war in Iraq. I think he really did believe that the war in Iraq was what he called a “dumb war.”

JAY: Oh, yeah. That’s what I’m saying.

BENNIS: Right. But I think–.

JAY: I’m saying the only reason he opposed it is ’cause he thought it was dumb, not for any other reason, not ’cause it was illegal.

BENNIS: Right. But I think–well, I’m not sure that he didn’t think that there were aspects of it that were illegal also.

But I think that the key is we’re looking at a situation now where the effect of the Iraq War, what it did to U.S. credibility around the world, has been very sharp in its impact. And I think that in the Obama administration there’s a growing recognition of that. They saw, you know, the demand for U.S. intervention in Libya. And then what were we left with? A disaster in Libya. You know, ask anybody in Libya now: are you better off today? Very few people are going to say yes. You know, it’s a violent, dangerous place for ordinary people. Nobody can live an ordinary life in Libya these days. So the U.S. is looking at the whole question of the militarization of diplomacy that had characterized the last decade and saying, maybe we need to change this.

JAY: Okay. We’re going to–in the next segment, we’re going to talk about this. You recently wrote a piece which talked about are we looking at a new period of diplomacy rather than militarization as the number-one go-to policy choice.

So we’re going to pick up the discussion in the next part of our series of interviews with Phyllis Bennis on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News. Thanks for joining us.