This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced on January 8, 2014. On Reality Asserts Itself with Paul Jay, Marisela Gomez, a doctor, and community activist, says one can’t arrive in the Hopkins community and not see the huge disparity between this institution and surrounding it, a community that’s been completely disinvested and abandoned.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And welcome to Reality Asserts Itself.

That was a segment from The Wire. That’s what most people think of (that have seen that show) Baltimore looks like. Well, Baltimore’s way more than vacant homes. And a lot of people weren’t all that happy that The Wire presented Baltimore almost as only that. But it is a big piece of Baltimore–30,000 abandoned homes and lots, and thousands of people displaced from their communities. And that’s part of the crisis of today’s Baltimore.

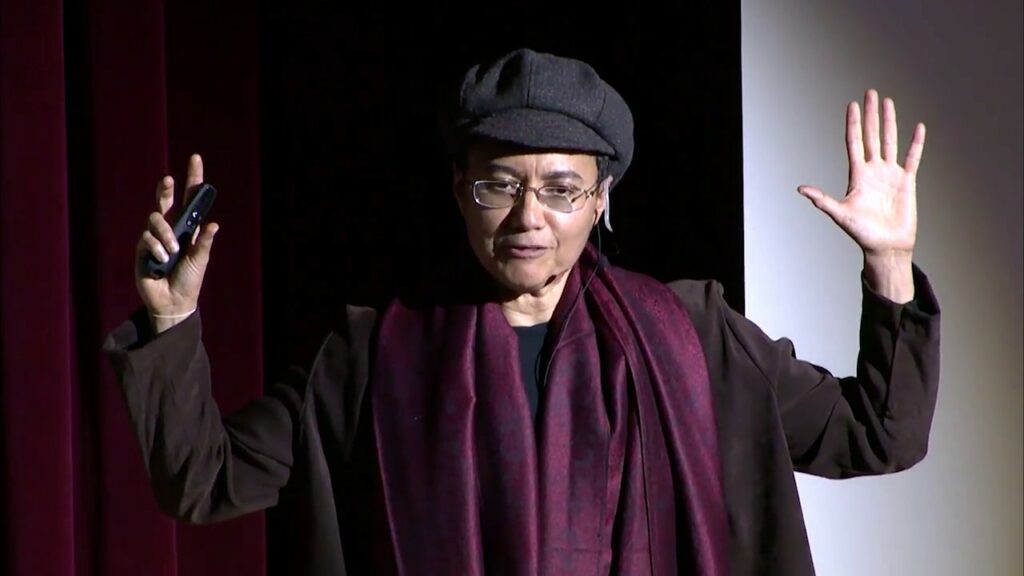

Now joining us to talk about these issues is Marisela Gomez. She’s a community activist, an author, a public health professional, and a physician scientist. After leaving the Air Force, she earned her masters of science at the University of New Mexico, her PhD, MD, and masters of public health from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. She spent over 20 years as an activist and an organizer in east Baltimore during and after her training at Hopkins. She also served as the executive director of Save Middle East Action Committee, a community organization in Baltimore that strove to represent community interest and needs in the redevelopment of what’s called Middle East, Baltimore. She’s also the author of Race, Class, Power, and Organizing in East Baltimore: Rebuilding Abandoned Communities in America.

Thanks very much for joining us.

DR. MARISELA GOMEZ, COMMUNITY ACTIVIST AND ORGANIZER: It’s my pleasure to be here.

JAY: Now, for those of you who watch Reality Asserts Itself, you know we usually start with a little biographical background of our guest so we can find out why they think what they think, what helped shape them as a person. And we’re going to do that with Marisela.

So you were born in Belize and came to the United States when you were pretty young. Where did you go?

GOMEZ: We went to New Orleans.

JAY: And that’s where you grew up.

GOMEZ: For four years.

JAY: And then what?

GOMEZ: And then I joined the Air Force when I was 17, and that took me to Wichita Falls, Texas; Omaha, Nebraska; and then Albuquerque, New Mexico.

JAY: So talk about–what year is this you join the Air Force?

GOMEZ: Nineteen eighty-two.

JAY: And so talk about where you’re at in terms of your political outlook. And what were the politics, the intellectual life of your home when you grew up? What was your vision of America that leads you to join the Air Force?

GOMEZ: Oh. Well, my vision of America at 17 wasn’t quite that positive, having been four years in the U.S. from Belize. I met the real America, not the one that they told you about in the other countries. I met the racism. I met the classism. I met the difference that America seems to embrace not so much with a loving arm, more with a lot of discrimination and oppression. So my view of America wasn’t so nice.

JAY: And New Orleans is one of the cities where social economic polarization is at its most extremes.

GOMEZ: Segregation is there, yes, like many cities in the U.S., and certainly was in 1982, in 1979 when I arrived as a young girl.

JAY: So when you’re 17, how conscious are you of this? I mean, you’re obviously aware of the disparity, but how political is that for you?

GOMEZ: Not very political. My politics was more aware in Belize, where I grew up, because there’s race and class separation there, too. So I was aware not so much from my household, my own home, but just aware that why did my parents have to leave when I was two years old to go to America so we could have a better life. I would notice that other kids had their entire kind of intact family, and we didn’t. I grew up with my grandparents in Belize. So it was very clear early that I came from a family that had to do things a little differently so we could get what everyone else would have. And that made me conscious that there was separate and difference. There were some people who had some and some people who didn’t, and that people who were lighter-skinned had more privilege than those who didn’t. So I learned that very early. And you could say that that was a political awareness from that time.

JAY: How aware are you of issues, for example, of U.S. foreign policy? I’m talking now at 17, before you join the Air Force.

GOMEZ: Not much, not very much at all; just aware that what I’m experiencing through high school is not nice, and I don’t want to be around that, so assuming that because I’m exposed to that in high school, that that’s what everything is like in New Orleans and Louisiana and wanting to get away from it. I remember I had a scholarship for a year after high school, and it was at a–I think it was in a college in Monroe, Louisiana. I knew enough about Monroe, Louisiana, to know that I wouldn’t be very welcome as a person of color, as an Afro-Latina, and I didn’t want to go. I remember very clear that I don’t want to go there, where people don’t want me around. I feel I’m experiencing enough of that.

And, you know, you always think the grass is greener. So, for me, getting away from that, the Air Force offered that, something I don’t know–I didn’t know much about it.

JAY: It wasn’t for you you’re joining one of the institutions that helped protect all of this segregation and system that you don’t like.

GOMEZ: Well, I learned when I joined that it did do that.

I had hope. I always have hope. I live in hope eternally. But I had hoped that the Air Force was what it said it was. You know, when I was recruited, I remember thinking, wow, this is great. I even took the Air Force sticker and put it in the car. And I thought, this is great. I put it on my dashboard.

JAY: So you were proud, you were proud to join.

GOMEZ: I was a proud American. I joined because this was going to be the thing that was different from what I had experienced four years previous, ’cause this was the Air Force, this was what upheld the country, and this was what you learned took care of everyone.

JAY: So this would get you away from segregation.

GOMEZ: Yeah.

JAY: And did it?

GOMEZ: No.

JAY: No? What happened?

GOMEZ: Are you kidding? No. What the Air Force did was it taught me a really big lesson. It taught me that racism and classism is a part of Americans’ culture. I was treated very badly for being a woman of color in the Air Force. I was made fun of, the way I talked, because I wasn’t educated, because I was 17, I had enlisted, which meant that I hadn’t been to college. And all that rebelling against college changed within the first year. I couldn’t wait to go to college, because I realized very quickly that my only way out was going to be through education, ’cause I certainly didn’t come from resources of wealth.

JAY: What experiences in the Air Force led you to the conclusion that this is America, race and class, racism and classism?

GOMEZ: The work schedules, the shifts you got, the way you were treated. I remember the first time I understood what spic meant was in boot camp when another enlisted woman from New York called me a spic. And I thought, what’s a spic? I didn’t realize that was me, I didn’t realize that it was bad, but I learned really quick. So I got some of that real brazen racism in the Air Force, and especially in boot camp, because, you know, in boot camp you’re demeaned and there’s a breaking that happens. And so the way you break people is to sort of find where you think their weaknesses are, and certainly, pushing the buttons of where you think a person is inferior would be a way to break a person. And so race and class was really used in that way.

You know, now that I’m older and a little bit more savvy–just a little bit–I understand kind of the social context of that way of doing things. But it’s not nice.

JAY: And what was your track at the Air Force? Were you being trained for something specific?

GOMEZ: I was being trained for a lab tech. So before you go into the military, they give you these tests, these aptitude tests to see where you fit. So I fit into science. I didn’t know. Who knew, right? ‘Cause I was tracked in high school also, you know, I was tracked in high school to be in administration, never science. I never was exposed or was thought of as being someone who could aspire to be a scientist, you know, ’cause I didn’t look like I should be a scientist. I didn’t fit the criteria. But the aptitude test for the Air Force put me in that. And so I was then–.

JAY: So there was some meritocracy in the Air Force, then.

GOMEZ: Absolutely. They–I tested into this area. And the next thing I know, I was in training to do laboratory sciences in Omaha, Nebraska. So I did that for nine months. And then that gains you entry to do laboratory medicine, medical or lab technology, laboratory technology. And that sort of pushed me into science, an area I had no clue about. Nothing. I had no idea what it was.

And from there, after learning that, oh, okay, I can do this, I guess this is okay, then I continued.

JAY: So on the whole your experience in the Air Force was a good one or not?

GOMEZ: You know, there is a saying: no mud, no lotus. The lotus doesn’t grow without the mud. And it’s true. The Air Force was a lot of mud. But out of the mud, depending on how you cultivate, there was a lotus, meaning I learned about science, I learned that I needed to really educate myself in this country, or in any country, really, if I was going to move out of this place where people felt it was okay to treat me inferior, and I learned that education was going to be the way to do that. So it gave me that.

JAY: So you go to university in New Mexico.

GOMEZ: I do.

JAY: You leave the Air Force.

GOMEZ: No. I–.

JAY: This is while you’re in the Air Force you go.

GOMEZ: While I’m in the Air Force, I pledge to myself that I will finish undergrad within the four years that I’m enlisted, ’cause I enlisted for four years. And it was crazy, but I did it. You know, I worked the shifts that would allow me to be in–to take the classes when I could at night. And when it came to the upper-level classes, I asked for night shifts so I could go to classes during the day. And I finished my bachelor’s within the four years. So it’s like a full-time job. Right? So I did my enlisted work, whatever I needed to [crosstalk]

JAY: And then you stayed, then, to do your master’s there.

GOMEZ: Then I was finished with my four-year enlistment, and then I went on to do a master’s in medical–no. My master’s is in toxicology.

JAY: And then you go to Hopkins.

GOMEZ: And then I go to Hopkins.

JAY: And you move to Baltimore.

GOMEZ: And then I move to Baltimore, yeah.

JAY: Now, I meant to say at the very beginning, when we saw that segment from The Wire, there’s one thing that struck me about watching The Wire–and I think I’ve seen every episode of The Wire–which is there’s not one mention of the word Johns Hopkins in the whole television show. And that’s kind of weird, because you cannot talk about Baltimore without talking about Johns Hopkins, because it really is certainly one of, if not the–maybe the most powerful institution in the city, certainly the biggest private employer.

GOMEZ: Absolutely.

JAY: So you go to Hopkins, which is a complicated story, and we’re going to get into the Hopkins story, because a lot of what we’re going to talk about is the role of Hopkins, especially in east Baltimore. And I should out myself, ’cause I have–I don’t know if it’s conflict of interest or what. My twins were born at Hopkins and got great care. But that’s part of the complexity of the Hopkins story. It is–as far as American hospital goes, it’s a good hospital. As far as the community around it goes, it could be another question.

So, just to finish your biography, so by the time you get to Hopkins, how’s your view of America, of the world changed? In terms of your political view, has it matured?

GOMEZ: It’s matured. I am exposed a little bit to community-building in Albuquerque. The university’s near downtown, University of New Mexico is near downtown. There’s a lot of abandonment and disinvestment in the area at that time. This is late 1980s. And I’m becoming more aware of how come, how come there’s all these abandoned buildings and people just hanging out and I’m seeking out community groups to get involved. And then I leave and come to Baltimore.

And then, when I arrive to Hopkins–.

JAY: And what year is this?

GOMEZ: Nineteen ninety. When I arrive to Hopkins, it’s amazing, because one can’t arrive into the Hopkins community and see the huge disparity between this institution, this ivory tower that sits there, and surrounding it is a community that’s completely disinvested and been abandoned. So, interestingly, my interest got started during my–had been piqued in Albuquerque now has really flared, because when I get to Baltimore, I can’t help but become very active and involved because the disparity is so clear.

What I say to people is I’m not sure why more people aren’t involved, because it’s either ignorance or benign neglect, I suppose, or intentional neglect to not see this disparity and not ask question why. And then, once you ask the question why, I think it motivates you to have to start to participate somewhat in what to do about it, because it’s so clear. It’s difficult to be there and not recognize that there’s something very wrong.

JAY: And you saw–I guess this is sort of an extension of your interest in health care, that health care isn’t just about hospitals and medicine.

GOMEZ: Absolutely not. The whole effect of someone’s health comes from the social environment, the social determinants. Our health outcomes are determined, more than 70, 80 percent of our health outcomes are determined by social factors. Our race, our class, our environment that we live in, our gender, our sexual orientation, our immigrant status, all these things have an effect on our health, you know, whether we get a headache, whether our immune system’s compromised, whether we’re more stressed out than someone else.

JAY: And you can see it. I’ve seen a map of Baltimore where they show health incomes by district of the city, and in the poor black areas, the infant mortality rates are not very different than some of the Third World infant mortality rates. You just go two blocks over into a wealthier white area, and, of course, they’re as good as or better than national averages.

GOMEZ: That’s correct. And the life expectancy also, it can change from ten, 15 years, from one community that’s low-income and of color to one that’s middle-class and white, primarily white. So these are social factors that are there. It’s not just a biological or a genetic predisposition. There are environmental factors. There’s a social context that we live in helps to determine who we are, how our health is, and how free we are to move through the world. And it’s hard, it’s difficult not to say that you’re aware of this.

JAY: Was there a specific experience you can remember when you came to Hopkins and you got a sense of the community around the hospital that sort of kind of really awoke you to these things?

GOMEZ: It was difficult to be inside a health-care institution which was such a premiere institution and obviously does a lot of good health-care work, a lot of great research. And yet to be also in a community next-door that had such huge health disparities, that had such poor health, that had not as much access to health-care resources, it was compelling to want to understand why is that. Like, if you have this cup really full over here and the cup right next to it is so empty, what is up with that? You know, why is that?

So this is very–this has always been, for me, when I see disparity, I want to know why. And being part of a medical institution that proposes that they are premiere, it became very clear quickly that they may be premiere in some things, but as far as being a good neighbor, as far as sharing what’s in that full cup, there was something very, very wrong and missing in that.

JAY: Okay. Well, in the next segment of our interview, we’re going to try to answer those questions why such disparity, but also the question why more people aren’t getting involved in doing something about it. So please join us for the next segment of our interview with Marisela Gomez on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

[simpay id=”15123″]

“Marisela B. Gomez is a community activist, author, public health professional, and physician-scientist. She received a BS and MS from the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, a PhD, MD, and MPH from the Johns Hopkins University. She spent 17 years as an activist/researcher or participant/observer in East Baltimore during and after training at the Johns Hopkins Schools of Medicine and Public Health. Past and current writings address social determinants and health, social capital and urban health, disparities in mental health care in incarcerated populations, disparities in substance use treatment, mental health care in the primary health care setting, community organizing and development, and mindfulness practices in organizing.”