Glaciers around the world are melting — and for the first time, we can now directly attribute annual ice loss to climate change.

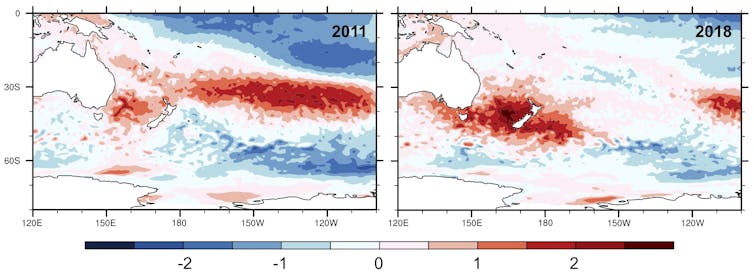

We analysed two years in which glaciers in New Zealand melted the most in at least four decades: 2011 and 2018. Both years were characterised by warmer than average temperatures of the air and the surface of the ocean, especially during summer.

Our research, published today, shows climate change made the glacial melt that happened during the summer of 2018 at least ten times more likely.

As the Earth continues to warm, we expect an even stronger human fingerprint on extreme glacier mass loss in the coming decades.

Read more: A bird’s eye view of New Zealand’s changing glaciers

Extreme glacier melt

During the 2018 summer, the Tasman Sea marine heatwave resulted in the warmest sea surface temperatures around New Zealand on record — up to 2℃ above average.

Research shows these record sea surface temperatures were almost certainly due to the influence of climate change.

The results of our work show climate change made the high melt in 2011 at least six times more likely, and in 2018, it was at least ten times more likely.

These likelihoods are changing because global average temperatures, including in New Zealand, are now about 1°C above pre-industrial levels, confirming a connection between greenhouse gas emissions and high annual ice loss.

Changing New Zealand glaciers

We use several methods to track changes in New Zealand glaciers.

First, the end-of-summer snowline survey began in 1977. It involves taking photographs of over 50 glaciers in the Southern Alps every March.

From these images, we calculate the snowline elevation (the lowest elevation of snow on the glacier) to determine the glacier’s health. The less snow there is left on a glacier at the end of summer, the more ice the glacier has lost.

The second method is our annual measurement of a glacier’s mass balance — the total gain or loss of ice from a glacier over a year. These measurements require trips to the glacier each year to measure snow accumulation, and snow and ice melt. Mass balance is measured for only two glaciers in the Southern Alps, Brewster Glacier (since 2005) and Rolleston Glacier (since 2010).

Both methods show New Zealand glaciers lost more ice in 2011 and 2018 than during earlier years since the start of the snowline surveys in 1977.

Images taken during the end-of-summer snowline survey show how the amount of white snow at high elevations on Brewster Glacier decreases over time, compared to darker, bluer ice at lower elevations.

Read more: Why long-term environmental observations are crucial for New Zealand’s water security challenges

Attributing extreme melt

Earlier research has quantified the human influence on extreme climate events such as heatwaves, extreme rainfall and droughts. We combined the established method of calculating the impact of climate change on extreme events with models of glacier mass balance. In this way, we could determine whether or not climate change has influenced extreme glacier melt.

This is the first study to attribute annual glacier melt to climate change, and only the second to directly link glacier melt to climate change. With multiple studies in agreement, we can be more confident there is a link between human activity and glacier melt.

This confidence is especially important for Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, which use findings like ours to inform policymakers.

Recent research shows New Zealand glaciers will lose about 80% of area and volume between 2015 and the end of the century if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise at current rates. Glaciers in New Zealand are important for tourism, alpine sports and as a water resource.

Glacial retreat is accelerating globally, especially in the past decade. Research shows by 2090, the water runoff from glaciers will decrease by up to 10% in regions including central Asia and the Andes, raising major concerns over the sustainability of water resources where they are already limited.

The next step in our work is to calculate the influence of climate change on extreme melt for glaciers around the world. Ultimately, we hope this will contribute to evidence-based decisions on climate policy and convince people to take stronger action to curb climate change.![]()

Lauren Vargo, Research Fellow in the Antarctic Research Centre, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.