This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced on December 12, 2016. On Reality Asserts Itself, Miko Peled tells Paul Jay that he fulfilled a childhood dream and became a member of the IDF Special Forces; then, he came to realize that everything he’d believed in was a lie.

PAUL JAY, TRNN: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on the Real News Network, I’m Paul Jay. We’re talking to Miko Peled. Miko was the son of a very prominent Israeli general. A general who after fighting in the 1948 War, came out after the 1967 War calling for compromise with the Palestinians. Miko grew up as an outcast along with his father and family, social outcast that is, as a result of his father’s opinions. But Miko, as you grew up you go to high school and you go to university. This continues. This issue of your father’s prominence and when does your father pass away? We’re leading up to you joining the military.

MIKO PELED: Yea well I join the military in 1980. Right after high school like all Israelis need to do. Many don’t today but you need to do. The atmosphere in which I grew up was of course that you volunteer for special forces then you do your best and there were 2 elements there to be honest. One element is kind of patriotic. But the other one is vanity because you grew up looking at these special forces guys with their red berets and their semi-automatic weapons.

JAY: Special forces women, they always have like models. Women that look like models in special forces gear.

PELED: Not in those days. That’s a new phenomenon, this kind of semi porn. But just an example, when I grew up, Netanyahu and his brother were in the military and they were good friends. I would see Bibi come home with his uniform and he was an officer in one of these special forces units and so on, that image was so powerful. So a lot of us young guys, that was our model, that’s what we wanted to be like. We didn’t know about the politics.

JAY: But you grew up in a very political household. Your father’s outspoken. You’ve been called an Arab lover and all of this. And he critique I assume, as part of this critique of Israeli policy, the role of the Israeli military, no? So does he encourage you to join? Does he discourage you? It seems a little contradictory.

PELED: Yes it does seem very contradictory. The way it’s portrayed is this liberal brand of Zionism says this is our land, this is our right, we must have a strong military to protect it. We may have to make sure that we don’t do things that are immoral. We have to maintain a moral army. We do maintain a moral army from time to time. There might be accidents or things that are wrong but basically we maintain the moral high ground. As a good soldier that’s what you do. You go in, you do your best and of course you make sure from the inside that you do the right thing when it’s up to you. But there was absolutely no discuss on whether or not I should sever at any point at any time. This was obviously a given. In fact, we look forward to it. Me and my friends we look forward to that moment, you come home in uniform and you carry that semi-automatic. Israeli soldiers take their weapon home. There’s a prestige that comes with this. Like I said, much of it is vanity. Not all of it is patriotism. Although it’s painted with patriotism. So anyway, so that’s what I do. I volunteer, I go through basic training, I do all this stuff. I’m in this particular unit for a whole year. And as I’m being trained, I go through several experiences which I just don’t understand. I talk about this in the book. The chapter in the book it’s called the Red Beret. I remember, we used to march at night. Marches were always at night. Very long marches. Night long marches. And we were walking through fields with crops and we’re trampling these crops. Now we’re in the West Bank. So, these are Palestinian fields. Many of the big Israeli army bases were in the West Bank at the time. And I run up to the sergeant and I say, look this must be some mistake here because we’re trampling somebody’s crops. You know of course it’s shut up and keep marching, you don’t talk to your Sergeant when you’re in training. So off we go. That’s what we do. Another experience later, we’re patrolling cities in the West Bank. We’re taken by bus to the outskirts of I believe it was Ramallah and we have our officer, our Lieutenant gives us some orders. We’re given batons and these plastic handcuffs. And I’m looking, I’m going we’re not cops. Why are we being given batons and handcuffs? We’re infantry soldiers. We’re commandos. One of the things our lieutenant says is, you are walking up and down, you’re marching up the streets. Anybody so much as looks at you, you break every bone in their body. Now we’re fully armed top to bottom unit of infantry soldiers. We’re going to be marching up and down a city. Everyone’s going to be looking at us. How’s anyone not going to be looking at us? It’s such a weird thing right. What are they supposed to beat everybody up and break their bones? I mean how does this all really make sense. I mean there’s no time to think because you’re given the order and then off you go. You’re on the bus then off you go. You’re given orders and you march up and down. You know what I mean? Everything is very fast. There’s no room for discussion or thinking. When you’re a soldier your lieutenant is like god. But little by little I was seeing these things. Then a year into my service-

JAY: Can I just ask you a question? I interviewed one of the vets for peace, American and he talked about boot camp and the extent to which before being sent to Iraq in boot camp he was being, they were being prepared to be willing to shoot women and children and one of the things he told me is you have an experiment or a mental experience. You have to imagine you’re in a market and someone’s trying to shoot at you and if you’re to shoot back you might have to kill women and children. Will you do it or not? If you answer is no then you haven’t passed. The training to be brutal, how much was that part of your training?

PELED: I had never went through anything like that. The way Israel does it is much more subtle. So we grew up, my generation particularly on the myth of the heroism of 1948. And the morality of our guys. At the same time, we learned stories about massacres and terrible things that had happened. The message is given in a much more subtle and roundabout ways. For example, there was a story of 35 soldiers who went, a unit that went on it’s way to some battle and on their way they saw a woman and a child. They didn’t harm them. Even though they were Arabs. Later on it turned out that that woman ran and warned people in the village that they were coming and they were all killed. Now you conclude what you conclude, you understand what you understand from this. See nothing has to be told. You don’t have to be told that you should’ve shot them. The story is evident and these 35 are considered great heroes. Everybody talks about them. You know there’s a kibbutz actually named after them. So, those are the kinds of stories that you learn growing up so you don’t need to be told the rest of it.

JAY: So, you’re order, someone looks at you and I suppose looked at you sideways or something. Did you and or any of the soldiers with you, did you break some bones?

PELED: No. We marched up and down. Nothing was going on. This was the late 1980s. everything was quite peaceful really on the face of it. At least on the surface, everything was quite peaceful. So, there was no reason to do anything and we never did anything. But then a year into it I had knee surgery and that was when I was sent to become a medic, fully intending to return to my unit, to my team as a medic. But the medic course was about 3 and a half months long and while I was going through that course I had time to reflect on all the things that I’d experienced and this whole image of the fighter, of the warrior, the red beret that I had already had and what it meant and where it was going. Putting things in context of the occupation in 1967 and it was clear to me that I’m not going back there. There’s no way that I can do this. The moral high ground that I thought we maintained was a bluff.

JAY: Was there a specific incident or thing?

PELED: No, it was just a gradual process that I realized. You know the medical corps is slightly more liberal and people who are more liberal anyway who thought the way I used to think before I as in the military. It was kind of a coming home moment in a way. Saying this is not who I am, this is not what I believe in. There were incursions already into Lebanon where Israeli commandos would go in and kill them and civilians were killed. So, there was already a sense that something is not right.

JAY: And how much role do you play? What happens with you with the full-scale Lebanon invasion?

PELED: Well what happened was I remained on that base as an instructor. I never went back to the unit. My unit of course had gone to Lebanon like all combat units did. I’m in this base as an instructor and really the only thing that was different for us is that we taught shorter courses and much faster because the army needed more medics. Then there was a sense of real betrayal because there was a moment that it was clear that the government was saying we’re only going in for a 40 kilometer incursion while the troops were already in Beirut. So, it clearly was not a 40 kilometer incursion. Then there’s Sabra and Shatila massacres. My entire belief system.

JAY: just very quickly for people that don’t know. We’ve done several stories about these massacres. But this is a Palestinian village essentially that’s slaughtered.

PELED: These are two Palestinian refugee camps, Sabra and Shatila, in southern part of Beirut that Israel didn’t actually go in and do the killing but they closed off the – they sealed the camps and they gave support to the Phalangist Christians who were actually committing the massacres. And Israel was supporting these killers.

JAY: Did you know that at the time?

PELED: Well there was an inquiry and it was clear that Israel had – I mean Israel was occupying Lebanon. So it was obvious Israel had something to do with it and the stories start coming out very, very quickly and then there was an inquiry and Ariel Sharon who was Defense Minister was found responsible and so on. But it was very clear from the very beginning that this was something Israel was behind. Even though they didn’t do the actual killing. The Israeli military was behind it.

JAY: What was your father’s attitude towards the Lebanese invasion and to your growing disillusionment. Because you start now getting more disillusioned at a kind of more fundamental level than perhaps he was.

PELED: At the very first anti-war protest he spoke. He said, this is the first time in the history of the state of Israel that there is a anti-war protest while the war is going on. And he became a strong supporter of the soldiers who refused to go into Lebanon. And supporter refuser movement and so on. Of course, he was unique in that. Very few people supported that. Certainly not former generals. There was a huge break of trust and faith in the system and the military. You know and it was clear that this was the true face of the state of Israel in many, many ways although hundreds of thousands came out to protest against Sharon and against the massacres. B But it was very, very clear that this was, things that I’d been taught, the things that I believed in were lies. You know. It wasn’t just me. It was a whole generation of us that kind of went through that process.

JAY: So, what happened next for you? You get your red beret.

PELED” Well I already had my red beret and I gave it up. When I went back after my. When I came at the end of my course to become medic, and I remained in that base, first thing I did was get rid of. Because the symbols that you earn are yours. You can wear the red beret even if you don’t go back and serve as one. But I said I don’t the symbols. I don’t want anyone to know. I have nothing to do with all of this. This has nothing to do with me, this is not who I am. I don’t care for these symbols. It’s all vanity. And it is all vanity. So somebody else can have it. Then I wasn’t involved in anything. I went overseas. I studied. I started a martial arts career. I did you know, my was kind of –

JAY: And you moved to the US.

PELED: I didn’t get to the US until several years later, intending to stay for a year or two. Then eventually I opened a business up in our karate school and just started a life here. Completely disengaged from Israel, from Palestine, from the whole thing. And I talk about it in the book too, the moment where I decided which way my life was going to go and I decided this was going to be my path and that was it. Then, much later on in 1997, suddenly I’m brought back into this. Violently brought back into this.

It was the mid 1990’s. It was a lot of suicide bombing. A lot of violence going on and my father had already passed away. He passed away immediately after Oslo. The Oslo agreement was signed. And I go back to Jerusalem for the funeral and it’s a kind of horrifying experience that’s really hard to describe in words. When you see this little coffin of a child go into the ground and you see the people you love, your family just completely broken you know. There’s no way to describe it. It’s horrifying.

JAY: She was walking on the street?

PELED: She was in street with friends and they were killed.

JAY: She was how old?

PELED: She was 13.

And this was the second or third in a series of very violent suicide attacks. So anyways that was the reality. That’s something that happened and then when I describe this in the book when I arrived at my sister’s apartment, this was 2 days later because I had to fly. It was packed with people who came to mourn, including Palestinians because Palestinians who knew my father. They came to express their heartfelt sorrow and regret that this has taken place. And by the way when I meet Palestinians everywhere, everyday, Palestinians come up to me and express their sorrow at this. Then I felt that something was wrong and something I had to discover. I had to understand something here. Then when I came back to the United States, I was looking for ways to get engaged. To talk to people, to find Palestinians, Israelis, anybody. Eventually I came across something that was taking place at the time, which were Jewish-Palestinian dialogue groups. This was in San Diego. There were several of them around the country and there was some news about them. They were called living room dialogue groups where Israelis that were Jews and Palestinians would meet and talk and I became engaged. I started participating in one of these groups and that was the first time I ever met Palestinians.

JAY: Around the time of the death of your niece, the reaction most people would expect would expect is fury against Palestinians but not only you, her family didn’t react that way.

PELED: Well yea. The first thing my sister said when she was asked about retaliation and revenge and who’s responsible was first of all, don’t talk to me about retaliation, don’t talk to me about killing more people. She said no real mother would want this to happen to any other mother. It was grief. In terms of who’s responsible she said, well who is it that’s maintaining this brutal oppression and occupation of other people? Denying them water and food and travel and shooting their children in the schools as they’re in their schoolyards and so on? You know, we are maintaining this and the Israeli government is responsible for all of these deaths including my niece’s death. That’s what my sister said. So, that was the approach immediately that she took and that her husband took and kind of that was the approach that was taken you know, individually and collectively. I think it has to do with the fact that we had already been exposed to the fact that it was an injustice. We knew what was happening. Our father had already, we’d been indoctrinated by him as to the reality of the Palistinians. Although everything was within the West Bank and Gaza. Nothing was ever talked beyond that paradigm. You know, the state of Israel is fine. There’s a problem in the West Bank and Gaza. It wasn’t until I actually met Palestinians for the first time and ironically the first time I met Palestinians was not in Jerusalem where I was born and raised even though it’s a mixed city supposedly, it’s in San Diego, it’s here in the United States. Because Jerusalem is a very segregated city, it’s a very racist city. The entire country’s actually segregated. That’s when I am exposed for the first time to this other narrative about 1948. What made the group that I was in unique is that 1948 was discussed. In many of the other groups the Jews and if there were any Israelis than the Israelis made it clear that 1948 is not something we talk.

JAY: That calls into question the very nature of the existence of the state.

PELED: The very legitimacy, exactly. That’s the holy grail. That’s something that we hold above everything else. We can talk about everything past that. 1967 and so on. This particular group broke all the rules. It just so happened that I was in that group. Everybody told their stories and their stories came from 1948. The stories of their family, the stories of how they ended in Kuwait or how they ended up in a refugee camp and how they ended up in the United States and so on and so forth. So I’m sitting with these people who look nice, decent, you know friendly people. Educated and everything. For the first time. They happen to be Palestinians. I feel a really strong connection to them. Many of them are from Jerusalem like I was. Yet they’re telling me something that makes absolutely no sense. Because I come from a place that I know what happened in 1948 because my family experienced it and they wouldn’t lie to me. The entire narrative that was taught to me, my family was a part of. So, what I know must be true. But these people are saying something that’s completely the opposite that absolutely makes no sense.

JAY: Well you have to then start to question some of the core beliefs of your father.

PELED: Yea a little bit later actually. That was the first step. Meeting Palestinians was really the first introduction I had that there was another story. I didn’t even know there existed another narrative, that there existed another story to 1948 because we’re never taught that. Then I start my own kind of investigation. Ilan Pappé and some of the other Israeli historians we began writing about this. Their books came out right around that time questioning the entire story of 1948.

JAY: What year are we in now?

PELED: This is like 2000, 2001. This stuff starts coming out and I actually called my brother. My older brother taught political science in Tel Aviv and I said to him, I was sitting with these Palestinians and they were telling me these stories and it’s not because they’re anti-Semitic or they’re extremists. This is not the issue. Then he said, well you should go check out Ilan Pappé and some of these other guys and what they’ve been writing because that will give you a good idea about what these people are talking about. So that was kind of what I did. Then when I would go back home I would venture into Palestinians towns and that was the first time I ever drove into a Palestinian town within what is considered Israel. In other words Nazareth and [inaud.] and all these towns that are predominately Palestinian-Arab. But they’re within the safe boundaries of the state of Israel. They’re all Israeli citizens. So they’re kind of good Palestinians, safe Palestinians.

JAY: And you’re allowed to go there. You’re not even allowed to go to the West Bank. It’s weird when I was there, if you have a foreign passport you can go but if you’re Israeli, you’re not supposed to go.

PELED: We’re not supposed to go but we go of course. And I’m beginning to experience the vast difference between the sphere where I grew up which is clean and safe and Jewish and orderly and this chaos which is the Palestinian towns. You know of course at first you don’t understand why is this such a difference? They’re citizens, we’re citizens. We always thought that they live the same way that we did. You know from time to time we get a glimpse and we’d wonder why is it so backward here you know? Of course, we thought something was wrong with them, which was really what the racist ideology teaches us. That the reason the people in the other is the way they are is because there’s something wrong with them. Not because they were deprived of our privilege. Then I start driving into the West Bank. Around 2005 I drove by myself for the first time to the village of Bil’in in the West Bank. Somebody told me that they had started this new nonviolent popular resistance movement. That’s where they began these Friday marches. These Friday protests. So I’d rented a car with Israeli license plates and I drove into the West Bank and the whole way, once I got into the West Bank, the roads with the potholes and it’s no more clean and it’s not this beautiful-y surface highways and these Arab villages everywhere and olive trees. Of course all I saw was an Arab waiting around some corner wanting to kill me. And I’m driving through, driving through, driving through until I get to Bil’in and I thought that this was going to be my last day on earth, there’s no way I’m coming home. They can identify me. I’m clearly an Israeli, I’ve got Israeli license plates. It’s a rented car. I mean you know, it’s everything I was always told you should never do, you know.

JAY: And of course nothing happened.

PELED: Well not only nothing happened, many good things happened as a result of it.

JAY: I had the exact same experience. In 2000 I rented a car and drove it all the way through. Stopped and had tea. Everyone couldn’t have been more friendly.

PELED: So many good things actually did happen as a result of that and I go back there all the time. It’s not even a question. Although the checkpoints are much tighter now. They’re not just kind of a bunch of soldiers and some locks. It’s like big terminals and all that kind of stuff so the travel is more difficult. But the West Bank is very pores so it’s not a problem. But that was when I began – remember being in Bil’in. Actually it was that visit to Bil’in and we’re walking with some of the guys and seeing the settlement that was being built on their land. That’s when it dawned on me that settlement is really not the word. These are big cities. Billions of dollars are invested here. This isn’t going away ever. There’s no way. This whole two state solution nonsense, and they’re talking about how this idea that maybe they’ll be on day compensated, they’ll be given some land somewhere else. You know trading land or all this nonsense. I thought this is absurd. They built a huge city here. Many of them. These are not little farms or little villages. We’re talking about massive, massive construction and massive investment. This isn’t going anywhere. This whole two state solution is nonsense. That was when I had the moment of clarity. I said, this is nonsense. The only way forward is complete equal rights and one democratic state and it’s not a Jewish state. It’s a state of all of it’s people and that’s it. That’s the only way these guys are ever going to be compensate. It’s the only way these guys are going to have any rights at all. And that’s the end of it.

JAY: Alright we’re going to pick up this in the next segment of Reality Asserts Itself with Miko Peled on the Real News Network. Thanks for joining us.

[simpay id=”15123″]

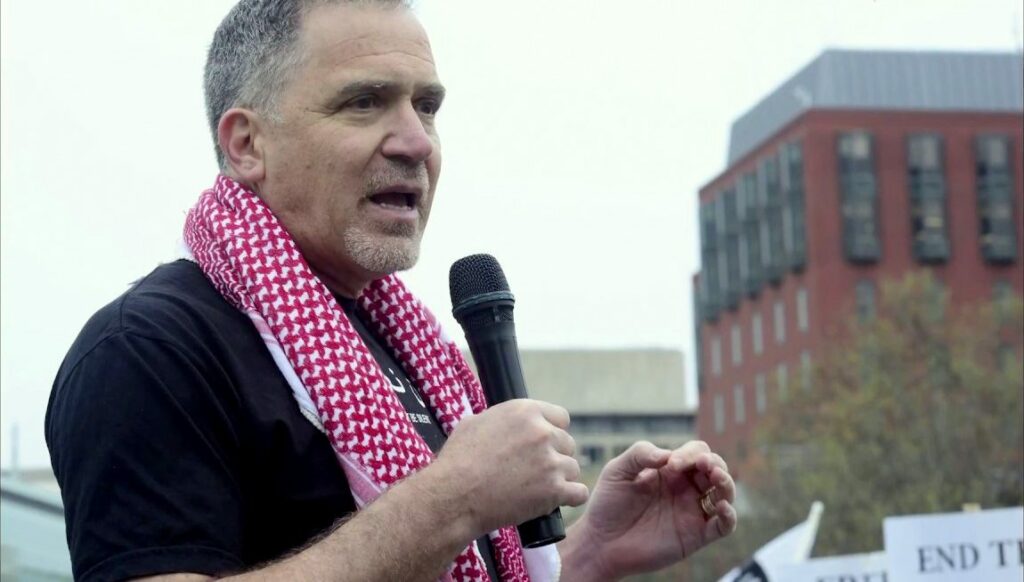

“Miko Peled is an Israeli-American activist, author, and karate instructor. He is the author of the books The General’s Son: The Journey of an Israeli in Palestine and Injustice: The Story of the Holy Land Foundation Five. He is also an international speaker.”