On Reality Asserts Itself, Trita Parsi tells Paul Jay that diplomacy, not sanctions and coercion, will help the U.S. work with Iran to find solutions to regional problems. This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced August 28, 2017, with Paul Jay.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

Paul Jay: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on the Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay and we’re continuing our discussion about the United States and Iran with Trita Parsi, who now joins us again in the studio. Trita is the founder and President of the National Iranian-American Council. He’s also the award-winning author or many books. His latest is, “Losing an Enemy: Obama, Iran, and the Triumph of Diplomacy.” Thanks for joining us again.

Trita Parsi: Thank you.

Paul Jay: We’re going to just kind of pick up the discussion where we were at, after part one, so I suggest if you haven’t seen part one, go back and watch it and then pick up here. Quite articulated by several Republican members of the intelligence committee and various other defense committees in Congress and such, they’ve talked openly about destabilizing Iran. They know they can’t invade Iran Iraq-style. The cost would be ridiculous. But they think they can start another … and I’ve talked to Iranian friends who say that people don’t quite understand that there are a lot of these kinds of fracture lines in Iran, that you could have another Iraq, and in fact it’s driving people that used to be very critical of the Iranian regime … Or government, I say, I don’t mind calling the American government a regime, too, but we’ll use the word government … the Iranian government to actually defend it now, because they’re so afraid of, the kind of American policy, if successful, doesn’t lead to, quote unquote, “regime change,” it leads to the destruction of Iranian society. What do you make of this kind of plans? I shouldn’t say how realistic it is because they thought the invasion of Iraq wasn’t realistic. In fact, the name of this show, Reality Asserts Itself, comes from an American who says the invasion of Iraq is realistic. And no, it wasn’t, but that doesn’t stop them from doing it again, does it?

Trita Parsi: We talked about why there is such a divergence of perspectives between Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United States, or segments of the United States, earlier on. The bottom line is that as a result of the invasion of Iraq, what had essentially balanced Iranians were now taken away and Iran was unleashed. By the Saddam Hussein regime falling, by the Taliban falling. Now, if you want to restore that old pre-2003 balance, there’s essentially two paths to it. Either you make Iraq and Afghanistan stunning successes and as a result they become so powerful that they are checking Iran, or, if that’s not in the cards, which certainly doesn’t seem to be the card because if there’s anything that the United States has clearly not been good at, it’s nation building. Well, if that option doesn’t exist, then the other way of restoring a balance is by cutting down Iran in size, whether that is military means or, alternatively, creating instability inside of Iran. The areas in which elements of the U.S. government have looked at, and particularly during the Bush years it was quite active in trying to see where it could work, is in the border areas where there tend to be ethnic and religious minorities, whether that is Sunnis in the Baluchistan area or whether it is Kurds or whether it is Arab-Iranians in Khuzestan and other places. That effort has been very, very active. It’s just not worked. The Iranian state’s ability to control its own borders as well as making sure that communications are not cut off and making sure that it could, despite the fact that many of the minorities actually have very, very valid criticism of the central government, which also precedes this regime, nevertheless the U.S. or any other entity has never managed to truly penetrate Iran in that way. We saw it wasn’t until just recently that ISIS even managed to get as deep into Iran as in Tehran. It’s not because they weren’t trying, it’s just that they hadn’t succeeded before.

Paul Jay: I’m kind of taken aback to some extent about, in the United States, the anti-war movement, the sort of progressive circles and such, there’s so little discussion about what the Trump administration is planning towards Iran. You get small discussions on it, certain organizations, relatively small, but the main progressive, main liberal, main left, barely talks about foreign policy at all, and do not focus on what’s clearly coming. These guys are planning another Middle East venture at some level. What do you make of that?

Trita Parsi: Well, I think first of all, I think there is a degree of awareness, a good degree of awareness, amongst the leadership of many of these organizations. The problem is that the Trump administration has lit so many fires that these groups that, to begin with, are underfunded compared to their equivalents on the right, are essentially spread thin and cannot focus on all of these different issues at the same time, and they end up becoming somewhat reactive in which what we’re focusing on is whatever Trump is immediately focusing on. Even though there is a realization that down the road, he’s going to do X, Y, and Z on Iran and North Korea, et cetera. The resources simply are not there to be able to cover-

Paul Jay: Isn’t it also a problem that the leadership of the Democratic Party, the majority of it, is on the same page as Trump when it comes to Iran?

Trita Parsi: When it comes to Congress I would say that certainly is, yeah.

Paul Jay: I’m talking about Congress, yeah.

Trita Parsi: That certainly is the case that a lot of-

Paul Jay: But the Chuck Schumers of this world.

Trita Parsi: Chuck Schumer did not vote in favor of the deal, and even though a very strong majority of-

Paul Jay: The nuclear-

Trita Parsi: The nuclear deal. Even though on the House side there’s been plenty of support for the nuclear deal amongst the Democrats, nevertheless, part of the problem has been that many of them also took a political risk in doing so because they opposed AIPAC on its absolutely number one priority. Even though none of them have lost their seats in the latest election as a result of defying AIPAC, there nevertheless is a sense among many of them that because they went out on a limb and supported a nuclear deal, they cannot afford to say no to AIPAC on a whole set of other issues.

Paul Jay: AIPAC being the big pro-Netanyahu lobby organization in the United States.

Trita Parsi: So there’s a sense that, you know, on other issues, particularly when it comes to regional issues, there’s a need to be hawkish on those. Again, I think there’s a failure to recognize that if everything else is moving in a negative direction and U.S./Iran relations, chances of being able to make sure that the nuclear deal lasts and endures is very, very small. The trajectory has to be positive and again, part of the reason why I think that we should take a look at that a second time is because finally, we have a good example of how actually the United States did manage to help bring about a different Iranian policy. If we do have genuine concerns about the other policies the Iranians have, we have an example how that can be addressed. That is not the example the Trump administration or hawkish Democrats in Congress are following. They’re going back to sanctions, pressure, threats, etc. That, frankly, has not worked. The only thing that has done is to be bring United States and Iran closer to a military confrontation.

Paul Jay: Cheered on by the Chuck Schumers of this world. When Trump bombed Syria, that air base, which was mostly a symbolic bombing, Chuck Schumer and others were saying, “Now he looks presidential.” I mean, in the midst of all this controversy and his administration being so much trouble, the one thing he can do is become a wartime president.

Trita Parsi: Certainly, and I think there is a certain degree of addiction to coercive policies that is as strongly held among some in the Democratic party as they’re held in the Republican side. Part of what I do in the book, actually, is to show that this narrative that it was sanctions that brought the Iranians to the table and it’s thanks to the sanctions that the nuclear deal was successful is frankly not true. Sanctions played a role, but we need to have a much, much deeper analysis of what actually happened and the limits of sanctions, in order to understand why did the nuclear deal work and how can we make sure that we pursue that same path, use that same blueprint, for future cases, whether it’s North Korea and others. If we are lulling ourselves into the belief, deluding ourselves into the belief that it was because of sanctions, I think we will be in for a very big surprise next time we have a case, because sanctions actually brought the United States and Iran very close to a military confrontation.

Paul Jay: Well, sanctions is clearly the operating theory of all the main media and the official American position. So, if it wasn’t sanctions, what is the story?

Trita Parsi: Well, the story that actually happened is that the United States pursued very aggressive sanctions, together with its allies. It had a tremendous negative effect on the Iranian economy, I mean, the Iranian currency dropped roughly 50 percent. The GDP contracted about 25 percent. There were riots at one point in Tehran, over these issues. But sanctions really hurt the Iranians, but it didn’t break them. What happened, though, is that the Iranians had a counter-measure. The more they were sanctioned, the deeper they dug themselves in on doubling down on centrifuges and expanding the nuclear program. This is what people, I think, have missed. Yes, sanctions theoretically gave the United States leverage for future negotiation. But during the period in which the U.S. was building up these sanctions and hurting the Iranian economy, the Iranians were not just sitting still doing nothing. They were doubling down on their nuclear program, building more centrifuges, learning more about how everything works and expanding their stockpile of low-enriched uranium. By the time they made, which one had actually gathered more leverage over the other? That’s the part, the alternative cost of sanctions, that is rarely discussed. What essentially happened was that the American and European sanctions clock was not ticking as fast as the Iranian nuclear clock. They were expanding faster and they had more maneuverability in order to be able to further expand it than the U.S. had, because sanctions essentially their apex somewhere between 2012 and 2013. In 2012, January, Leon Panetta, then Secretary of Defense, publicly stated that Iran is roughly 12 months away from, their break-out time is 12 months, meaning, if they were to decide to build enough fissile material for a nuclear bomb, it would take them 12 months. By January 2013, one year later, that break-out period had shrunk to 8 to 12 weeks. The president realized at that point that if nothing changed and they were just sticking to the sanctions path, it was far more likely that the Iranians would have a nuclear weapons option and be able to present the United States with a nuclear fait accompli or than the Iranians collapsing and begging for mercy because their economy had died. So sticking to sanctions would lead to two very bad options. At that point, the president decided to go back to the secret negotiations in Oman and for the first time, accept Iran’s red line, which was accepting enrichment on Iranian soil. That’s what opened up the negotiations.

Paul Jay: The Iranians said they had no nuclear weapons program. American intelligence agencies in their last national estimate, which I forget the year, was-

Trita Parsi: 2007.

Paul Jay: … 2007, said there was no nuclear weapons program. So are you saying there was a nuclear weapons program?

Trita Parsi: They said that … The 2007 NIE said that experimentation with things that could be used for military purposes had stopped by 2003.

Paul Jay: 2003, right.

Trita Parsi: And that was a big statement in and of itself, because the Bush administration were saying that they were essentially actively working on a nuclear weapons program. But the U.S. intelligence estimate itself said that prior to 2003, there were violations or at a minimum, suspicious activities.

Paul Jay: Of which the IEA had never actually had evidence of.

Trita Parsi: Not that had been presented, but there was a strong conviction amongst many parties that there were something the Iranians had done in the past that they had not fully disclosed and they wanted to get to the bottom of it. That’s one part of the sides deals to the nuclear agreement, not a side deal but an annex, if you can say, to the nuclear deal, in which the IEA got access to people in order to complete its investigation on what the Iranians had done or not.

Paul Jay: Because there’s one theory goes that the Iranians were actually telling the truth that they didn’t have a bomb program going, but they wanted it to look like they did or they wanted to look like they were approaching break-out. But it’s one thing to have enough material to create a bomb and it’s another thing to actually have the technology for a bomb and being able to deliver a bomb, which they claim they weren’t doing.

Trita Parsi: And there’s also another explanation, which is that prior to 2003, they may actually have had things that were illegal, that were experimentation, etc. They had stopped it, which the IEA and the intelligence, the U.S. intelligence acknowledge, and they were worried that if they came clean on what they had done in the past but had stopped, they would still be punished for it. So as a result, they were not opening up their books entirely because they were not going to be punished for something that they had stopped doing. The question that the Europeans in particular felt was important was that, well, are we going to make sure that they don’t do it again in the future or are we going to be obsessing with what they did in the past and punish them for that? And they lean towards, well, if we don’t get to the bottom of that, but we still make sure that there’s no path for them to be able to have any weaponizations, experiments, or weapons program in the future, that’s more valid and more important.

Paul Jay: When you said the Obama administration realizes they’re just weeks away from break-out, they’re not weeks away from having a bomb?

Trita Parsi: Not weeks away from having a bomb, but weeks away from being able to have the fissile material to build a bomb. That was one of the measurements. It was originally the Israelis that pushed for that measurement. But the bottom line is this, whichever measurement one were to use and however valid or not valid it would be, the reality was that the U.S. could no longer really squeeze the Iranians on sanctions, because the pain of the sanctions was waning. Whereas, the Iranian ability to further escalate their nuclear activities had not the same degree of limitations. If you wanted to use that leverage that sanctions had produced, you would have to do it fast because the leverage was actually decreasing. But therein lies the issue. The president recognized that he had to accept enrichment on Iranian soil. That’s something the Obama administration actually always had planned to do, but the plan was to concede that point to the Iranians at the end of a negotiation. Instead, now, the United States had to concede that point at the very outset in order to get real negotiations. If we had accepted enrichment on Iranian soil at a much earlier stage, chances are that a deal would have been found at a much earlier stage when the alliance had not expanded their program to this point, had not learned so much about the fuel cycle, and as a result, a better deal, so to say, could have been found if we did not have such an unrealistic negotiating position to begin with. Because in 2003, when the Iranians offered to open up their nuclear program for full transparency, in a proposal to the U.S., they had roughly 150 centrifuges. By the time the Obama administration met the Iranians in Oman, they had roughly 22,000 centrifuges. They had 10,000 kilos of low enriched uranium. This is the point, I think, has not been acknowledged. That yes, all of these added sanctions, et cetera, our quite impressive web of sanctions that really hurt the Iranian economy, but what they did on the nuclear front, to a certain extent in response to this, I quote one of Rouhani’s closest advisors. His chief of staff, in an interview, said, “Well, some of these things, we never actually needed.” Some of the expansion that they did in the nuclear program. “But it was important to signal to the West that if you think you can get anywhere by just using pressure tactics, the pressure will produce the opposite of what you’re seeking.”

Paul Jay: But that’s what some people are theorizing. That’s actually was the point. It wasn’t that they were planning to build a bomb. They wanted just to show that they could and counter-pressure the pressure.

Trita Parsi: There was certainly counter-pressure. It was a chicken race about who could actually put most pain on the other side. But I think we have to give the Obama administration a lot of credit, because almost no other administration would have been willing to face the criticism at home that the U.S. had shifted its position from zero enrichment to something different. Zero was adopted under the Bush administration. In fact, many of the people that left Obama administration, such as Hillary Clinton, seemed quite disinclined to accepting enrichment. Had enrichment never been accepted, there would not be a deal right now. Had those people in Washington who criticized the nuclear deal, who said, well, we should have just continued with the sanctions for another year or so to really break the Iranians. Well, actually there was far greater likelihood that if the sanctions path was continued, it would either have led to a war or it would have led to the Iranians having a nuclear weapons option, mindful of how fast they were progressing.

Paul Jay: This is where we go back to the discussion in the first segment, that the Obama administration, their actual objective seemed to be concerned about a potential bomb, although I still think we have to keep saying, there’s no evidence there was a bomb program. But the Saudis and Israelis, it’s far more about regional geopolitics than it ever was about the bomb. So for them, the agreement just meant accepting Iran as a regional power and that’s the fundamental thing they don’t want to do.

Trita Parsi: Absolutely. That’s really the core of it. I quote … It was a very hush-hush meeting that was held in Europe, 2012. A very senior Israeli official was there, as were members of the Iranian nuclear negotiating team. This is obviously very far away from the eyes of the media. At one point, this very senior official looks straight into the eyes of the Iranians and says, “This was never about enrichment. Enrichment is not important.” What Israel wants to see is what he called “a sweeping attitude change” from Iran. If we dug deeper into what he was saying essentially was, these Israelis are never going to accept the United States accepting Iran without Iran accepting Israel.

Paul Jay: And accepting Israel means cutting ties with Hezbollah, because it’s really more about Hezbollah than anything else for Israel, isn’t it?

Trita Parsi: It means a whole set of different things.

Paul Jay: Hamas, Hezbollah, but mostly Hezbollah, I would think.

Trita Parsi: It also means that the Iranians would then accept that Israel is a nuclear weapons state. Which, in a side conversation later on, the Iranians signaled that Iran will recognize Israel … Actually, what they said is that Iran wants Israel to be a member of the NPT as a non-

Paul Jay: Non-Proliferation Treaty?

Trita Parsi: Yeah, non-proliferation-

Paul Jay: As a non-nuclear power.

Trita Parsi: Exactly.

Paul Jay: In other words, you give up your nuclear weapons and we’ll recognize you.

Trita Parsi: Exactly, and the Israelis actually picked up on what that meant, because only states can be members of the NPT. So in a way, the Iranians were saying that they would accept Israel if Israel gave up its nuclear weapons and Iran was on the path of giving up its options of building the nuclear weapons.

Paul Jay: Which of course, Israel won’t do.

Trita Parsi: Well, Israel itself has said that they won’t be the first one to use it and if there’s real peace, they’ll get rid of it, so the Iranian statement wasn’t that different from what the Israelis themselves were saying.

Paul Jay: Well, the Israelis are not going to give up nuclear weapons. Doesn’t matter what anybody else says. In the first segment of the interview … Well, actually, before we go on to this, let’s just talk a little bit more because you actually had a role in advising the Obama administration, so you had real conversations with them. Why were they so sure that the Iranians were actually building a bomb when there seems to be so little evidence that they were?

Trita Parsi: Well actually, the Obama administration, particularly once the negotiations really took off after the Oman meetings, it was quite clear that they were very confident that the deal that they were designing would disable the Iranians from being able to pursue nuclear weapons and that ultimately, whatever intent Iranis may have had early on, that intent had changed. It came at it from a very different perspective than the Bush people, for instance, who were completely convinced that the Iranians would be pursuing nuclear weapons regardless. They would adopt the Pakistani line of, “Doesn’t matter if we eat grass, we’re going to have to have a nuclear weapon.” That was not the attitude at all.

Paul Jay: Because the Bush/Cheney types put themselves in Iranian shoes, and that’s what they would do.

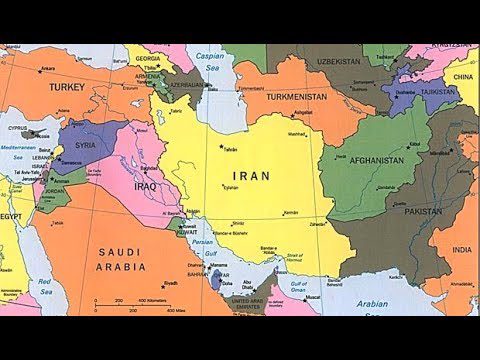

Trita Parsi: Yeah, because they actually think along those lines that a nuclear weapon would be so valuable. It’s actually been interesting. I’ve been in a lot of track two meetings, et cetera, and this is a position the Iranians have taken for quite some time. The Shah started this program under pressure from the United States. The United States wanted Iran to have a nuclear program, and that nuclear program would be of course with Westinghouse and other American companies. The Shah wanted to have a nuclear weapons option, being able to have the technology but not past that line, because ultimately, for Iran, mindful of its geopolitical conventional superiority, it was not a positive, strategically, to have a nuclear weapon. Because if Iran … you can take a look at the map to see how big it is … if Iran were to build a nuclear weapon, the risk would be that it would initiate a cascade of other countries also pursuing nuclear weapons. Well, if Iran, with its massive size and population of 80 million, would have nuclear weapons, and tiny Bahrain also would get nuclear weapons, well, Iran and Bahrain would have just put themselves at parity with each other, because now both sides have the dooms weaponry, they’re essentially canceling each other out. The biggest loser in that scenario would be Iran, because Iran had a vast conventional superiority prior to nuclearizing the region.

Paul Jay: It’s just ridiculous, this idea that Iran’s going to get a bomb and drop it on Israel. I mean, there’d be no Iran left. They know that everyone knows that, starting with the Iranians.

Trita Parsi: I interviewed one of Ariel Sharon’s advisors who very clearly explained something to me that completely, then contradicts the Israeli public line. He said, “Whatever Iran does to destroy Israel, it will never destroy Israel’s ability to destroy Iran in turn.”

Paul Jay: Or the United States’ ability.

Trita Parsi: Yeah, and what he’s referring to there is that Israel has several Dolphin German-made submarines that are nuclear-equipped. Meaning that if the Iranians were to be so foolish to ever use nuclear weapons, that they don’t have, against Israel, they would still not be able to destroy Israel’s submarines, and as a result, Israel has a second strike capability, which would mean an automatic destruction of Iran. But what’s so interesting with his explanation of this is that that’s very much based on the idea that you can deter the Iranians, that they’re rational, which is of course completely contrary to the line that Israeli officials have taken for the last 20 years.

Paul Jay: Well, Israeli politicians. Most of the leaders of the intelligence community in Israel have actually said Iran is not an existential threat. It’s the political rhetoric that talks that way.

Trita Parsi: The political rhetoric, and also have to recognize that there are also political entities, personalities that have been very clear that they don’t view Iran as an existential threat. Ehud Barak is probably the most senior one. He’s been consistent on this point since the early 1990s. And his line has been that that would be an insult to Israel, because Israel is a tremendously powerful country. To say that Iran is an existential threat is to diminish Israeli power. He’s had an interesting history with the Iranians, as well. But bottom line is, Netanyahu really came to personify that concept that Iran is an existential threat.

Paul Jay: Okay.

Trita Parsi: And that kind of put him in a position in which he had no flexibility, no ability to go back to the Israeli public and say, you know what? This is actually a good deal. You know that stuff I said about them being an existential threat? Well, we just struck a deal with that existential threat. That’s not possible, politically.

Paul Jay: Okay. In the next segment of our interview, we’re going to talk a little more about U.S./Iranian relations and dig in further into the issue of the role of Israel in all of this. Please join us, with Trita Parsi, on Reality Asserts Itself, on the Real News Network.